The Many Jobs of a Religious Leader

Pastor, Priest, Imam, Rabbi, Chaplain, and everything else.

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

Every once in a while, someone would ask me how I became a pastor. I completely understand the impetus for the question, by the way. If you didn’t grow up around religion, the pathway to ministry can seem somewhat opaque. Let me just quickly lay out my story.

When I was 20 years old I needed a summer job and wasn’t having much luck finding work back in my hometown. In one of my ministry classes the professor mentioned that a church not too far from my house was looking for a three month youth ministry intern. I grew up going to church all the time, spent a lot of time helping out in my youth group as a teenager, and had taken a couple religion classes at Greenville College. So, I sent in my application.

Well, I got hired. That three month appointment turned into three years. When I left that job to go to grad school in Carbondale, I asked our regional minister if there were any churches that needed a pastor. He found me a position in a tiny congregation in Marion, Illinois where I became the senior pastor at 23. I left that position a year later only to be quickly called to pulpit supply at First Baptist of Mount Vernon, Illinois. Which turned into an interim position. Which turned into a permanent post that lasted nearly 18 years.

If you asked 100 ministers to tell you their own story, I am going to bet that you would find that there are some general commonalities, but a lot of them would just be a weird set of coincidences. Just like mine. But there’s a really rich dataset at the Association of Religion Data Archives that can help demystify how clergy got their job and also how they manage the financial aspect of being a pastor.

It’s called the National Survey of Religious Leaders, and it contains questions like: did you have a different career before ministry, were you on the staff of your current congregation before you became the leader, and were you a member of the congregation before you became paid staff?

The one really significant finding for me is that very few members of the clergy report that they went straight into ministry as a young person. In fact, 66% of the folks in the sample of religious leaders said that they had a career outside religion before they became a member of the clergy. I’m not sure if the average person knows that - most pastors you see didn’t go straight from Bible College to Divinity School to full-time ministry.

It’s also important to note that a sizable percentage of them had to ‘work their way up’ before they became the leader of their local house of worship. For instance, a quarter of all senior clergy were on the staff of that same congregation before they rose to the top of the organizational chart. There’s a often unspoken understanding in most Protestant churches that the youth minister is basically a senior pastor in training.

I was also pretty surprised to see that about one in five religious leaders actually started out as an active member of the laity of their house of worship. This often happens in more “low church” traditions that don’t place a great deal of emphasis on formal theological education. That was certainly the case in my denomination - the American Baptist Church.

Beyond the question of how clergy got their job, there’s a nice little battery of questions in the National Survey of Religious Leaders that focuses on what clergy do with the rest of their time. They were asked if they had any other job, if they served as a chaplain, or served an additional congregation.

About a third of all the clergy in the sample had some type of non-ministry related occupation in addition to their primary role as a religious leader. That definitely tracks with my own experience in my denomination. Very few American Baptist churches in rural Illinois can support a full-time staff member. I was bi-vocational my entire time in ministry. There’s no way that I could have supported our family on my part-time income at the church. This seems fairly common.

In addition, there were a significant portion of clergy who worked in multiple congregations or who are also chaplains in a variety of contexts. From looking at some of the other questions on the instrument, I can see these were positions in hospitals, universities, prisons, or nursing homes. I also found that a small, but notable portion (7%) said that they both worked in multiple congregations and were also a chaplain.

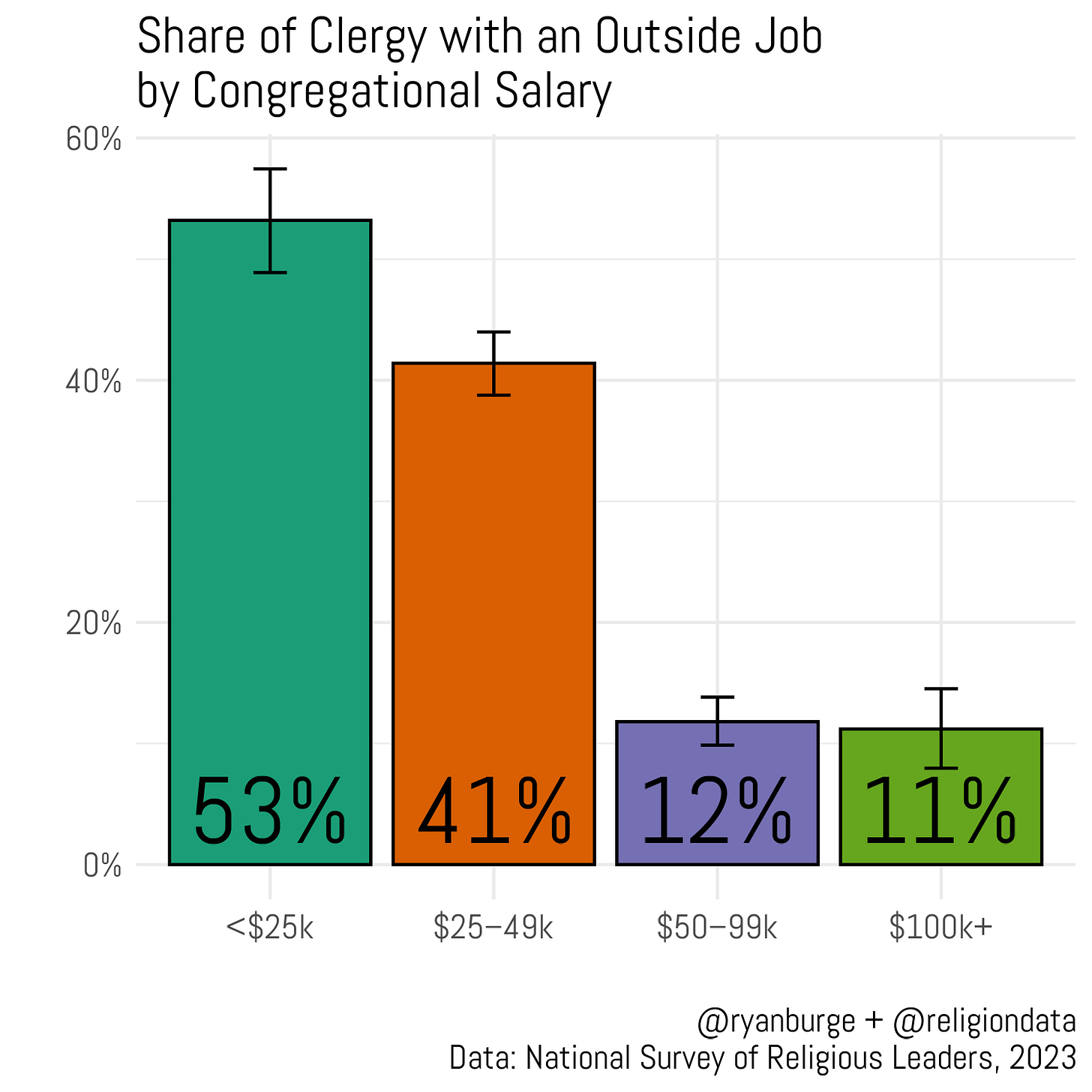

Why do this kind of outside work? Well, the simplest hypothesis is that these religious leaders need the additional compensation to help support their families. I can test that out because the survey asked household income.

I just calculated the share of the sample who said that they had any kind of outside employment based on four categories of income and there’s a really clear inflection point in the data. For pastors who have a total income of less than $25,000 per year, a majority are engaging in work outside their role as a member of the clergy. That does drop a little bit when looking at incomes between $25,000 and $50,000 per year.

But once a pastor hits that threshold of at least $50,000 per year, there’s a huge decline in the share of clergy who have any kind of “side hustle". It’s noteworthy that there’s no difference at all between households making $50,000 to $100,000 per year and those who make at least six figures.

This all does make sense, though. Those top two income brackets likely represent pastors who are considered full-time staff. They have higher incomes but they are also given benefits like health insurance and a retirement plan. On top of that there are other types of compensation like a housing allowance, as well.

Beyond questions of just working in these different roles, the survey asks clergy to estimate how many hours they work in these different areas.

In this sample, the average clergy person indicates that they work about 34 hours per week for their primary congregation. One nice feature of this survey is that it doesn’t just include full-time religious leaders. So this estimate does include a fair number of part-timers. That’s one of the reasons that this number is not at least 40 hours per week.

You can see that the average religious leader who said that they worked an outside job said that it took up about 28 hours of their time. For those serving multiple congregations, those ministers were devoting about 15 hours a week to that occupation. Meanwhile, chaplaincy took up a bit less time at 7 hours per week.

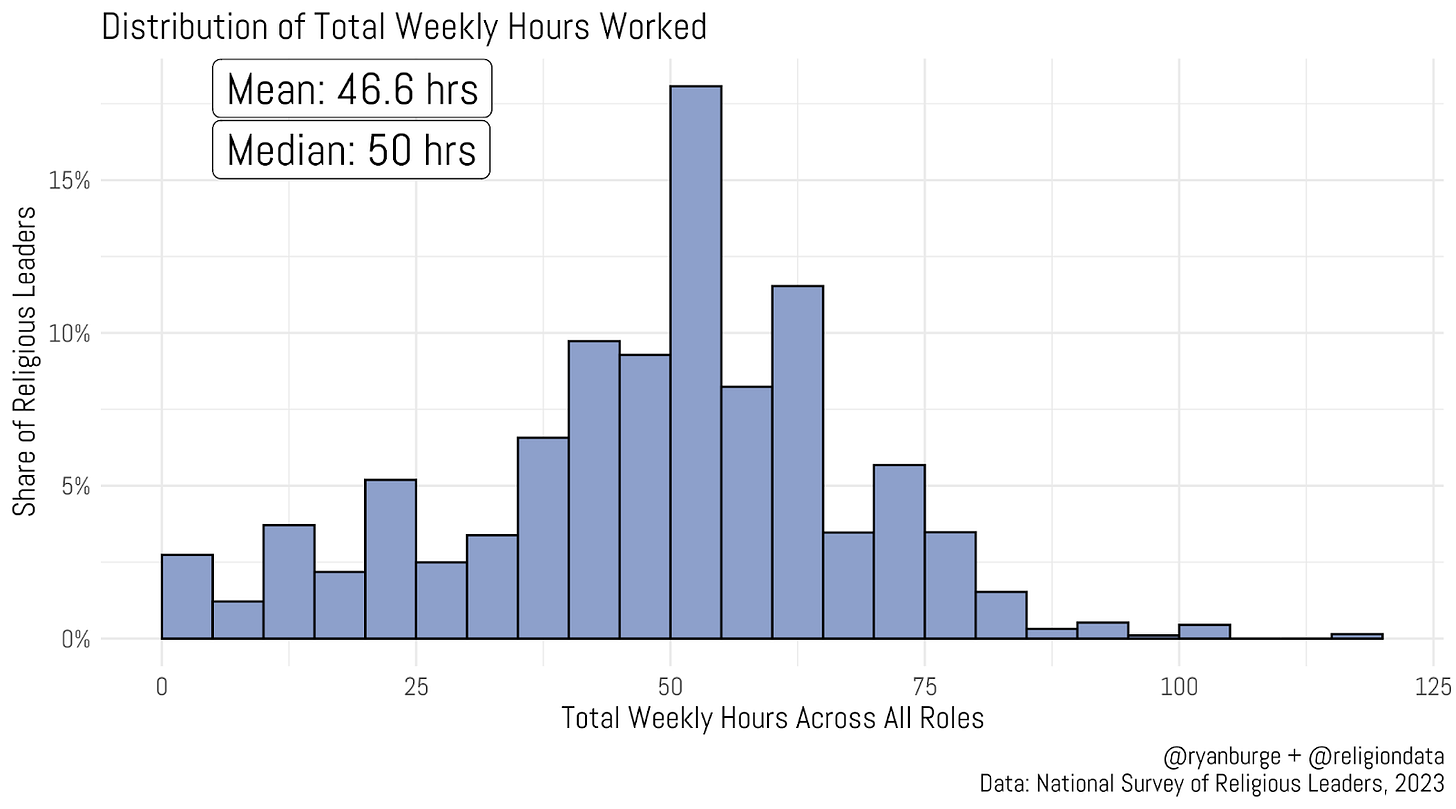

To get a sense of whether the average member of the clergy was feeling overworked I just added up the totals for each minister from the prior analysis and visualized the distribution.

You can see from this graph that the most likely answer to these questions was a total of about fifty hours per week. That was the median response. The mean was just a bit lower, at 47 hours per week. In terms of actual percentages, about 10% of the sample reported 20 hours of work per week or less. On the other side of the distribution - nearly a quarter of the religious leaders in the sample said that they were working at least sixty hours a week across all of their occupations.

I wanted to understand what factors led a member of the clergy to report a lot of hours across all their occupations. One question that caught my eye was about how many years that the religious leader had served as a member of the paid clergy. I wondered if younger members of the clergy were all gung ho about their careers and were burning the midnight oil. Or maybe as one moves along in their career, they take on leadership in larger and more complex houses of worship that tend to eat up more time.

I have to admit that I can’t find any kind of discernible pattern when looking at this result. The ministers who had served between 20 and 30 years as a member of the clergy reported the fewest number of working hours at 41. The group that indicated that they worked the most? Folks who had been leading congregations for between 30 and 40 years. Their average number of hours worked was 53.

These results are just so scattered that I can’t really say whether it’s the older folks or the up and comers who are working the most. And this may go back to what was discussed in the beginning - every path to ministry is completely unique and lots of members of the clergy have an interesting mix of income streams that aren’t easily summarized in descriptive statistics like this.

Some takeaways.

Most ministers didn’t start out that way. In fact, two-thirds had another career before they became a religious leader.

Lots of clergy do other things outside their primary occupation. Some serve multiple congregations, others are chaplains. A significant number have outside employment that has nothing to do with religion.

Clergy work more than forty hours a week across all these responsibilities. And a worrying share (25%) are spending 60 hours a week or more across their various jobs.

Leading a religious congregation is both a burden and a blessing. Anyone who has spent significant time in vocational ministry can attest to that. But despite all its challenges, the data indicates that hundreds of thousands of pastors, priests, imams and rabbis are finding a way to make it work on a weekly basis.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

As Ryan adapts to his new campus with a very large Jewish presence, some of the ways we differ from the Protestant majority will likely come his way. One is the creation of our Rabbis, which is in transition. In my era, Class of ’73, men went to university then applied to a seminary, much as one would apply to medical or law school. There was a pipeline that fed this. Usually the applicants were part if their denominational youth group clique as teens, went to a Jewish sponsored summer camp, a university with a large active Hillel, then applied for their divinity school, mostly sponsored by their denomination. Much of that feeder system has broken down in the last decade or two, with the creation or expansion of a few new seminaries that attract career changers.

One of the astute observers in the Jewish blogosphere pursued this, starting with a landmark article in The Atlantic by Shira Telushkin about a year ago. Since Ryan thrives on data, this blogger took an analytical approach. https://furrydoc.blogspot.com/2024/05/rabbis-going-forward.html What he did, not having a survey, is he created his own. He read every graduation program from every major non-Orthodox seminary for 2024. They often contain bios of the year’s grads. In the absence of a bio provided by the school, he did a web search on each individual. Total of about eighty new rabbis, about half female.

He found a variant of what Ryan’s more formal statistics revealed. That pathway to seminary and Rabbi as career professional for a synagogue has changed. These graduates did other things before opting for rabbinical education. Their options for employment as rabbis have many options other than leading congregations. Relatively few go directly to a synagogue. The reasons for this are many, but the umbrella groups of denominations usually impose some type of restrictions on who they may hire.

The going rate salary for congregational rabbis is about double the salaries in Ryan’s survey, so once there, nearly all are full-time. And the ones I know tend to keep long hours and answer to 200+ bosses.

What Shira addressed that the blogger did not was what did the men, now also women, who would have gone to seminary from college opt to do instead? Many PhDs, a few lawyers, other things that the career changers who went to seminary late in life had been doing before opting for Rabbinical study.

One of the things I have wondered about is not addressed here and its this. Do members of clergy feel isolated in their interactions with others. Do people tell them jokes or talk about baseball.