Are Members of the Clergy Miserable?

And what factors lead to their life satisfaction?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

I have been a paid member of the clergy for almost my entire adult life. I took a job as a youth ministry intern in the summer of my sophomore year in college that ended up being a three year gig at an American Baptist Church in Centralia, Illinois. Then, I was the pastor of a small Baptist church in Marion, Illinois during my first year of graduate school. They wanted me to wear a suit when I preached. I owned one suit. That suit didn’t last very long. Eventually an older gentleman in the congregation slipped me a hundred dollar bill and told me to buy another one. I was grateful.

Then, I tried to leave the ministry. I took a job as a graduate assistant in my graduate program. I still have the email with the offer. My monthly stipend on a nine month contract was $1,128. Money was going to be tight. So when a church in Mount Vernon, Illinois called me up and asked me to preach one Sunday, I was happy for the extra income. Then, they asked me to do it again the next week. And somehow I became the interim pastor at First Baptist Church of Mount Vernon, Illinois in October of 2006. I’m still there.

After being a bivocational pastor for such a long period of time, I’ve realized that it’s not something I could do for my primary occupation. It’s an incredibly difficult job - emotionally, spiritually, relationally, and financially.

The data reinforces that point. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research polled some pastors about this topic and more than half have seriously considered leaving their role, including one in ten who say that they have these thoughts often. The Barna Institute launched the Resilient Pastor Initiative to try and understand what factors could keep clergy in their respective pulpits.

The three leading causes for pastors who have considered quitting were:

The immense stress of the job - 56%

I feel lonely and isolated -43%

Current political divisions - 38%

This is a topic that I hadn’t really dug into much with survey data, but I was delighted to see that the Association of Religion Data Archives had been asked to house some survey results from the National Survey of Religious Leaders. According to the description, this is a nationally representative sample of 1,600 clergy from all parts of the religious spectrum. It’s important to note that this survey was conducted in 2019 and 2020 - and very few respondents were taking the instrument after COVID-19 lockdowns had begun. Keep that in mind when interpreting these results.

I really wanted to key in on a few questions about job/life satisfaction. The survey replicates a question from “The Satisfaction with Life Scale.” The statement is simply: In most ways my life is close to my ideal.

These results are surprisingly encouraging and clearly defy the common narrative that lots of pastors are miserable, burn out, and on the edge of leaving the ministry behind. About one in five say that they completely agree with the statement that their life is close to ideal. And half the sample says that they moderately agree with that statement.

In total, seven in ten clergy seem pretty pleased with the way things are going in their life - that’s especially true when adding the 16% who slightly agree with that statement. Just 6% of all clergy disagree with that statement and 7% don’t seem to have an opinion on the matter. Recall that this data was collected pre-pandemic, but it’s an incredibly positive result.

I tried to poke around online and find other examples of this question being asked to other population groups. The mean score for this was 5.6 in the clergy sample. Among members of Israel’s Defense Force it was 4.7, among some university students it was found to 5.23. Among nurses it was 3.81. In a sample of people living in Colombia it was only 3.67. The long and short of it was this - I can’t find another population group that scores higher on this metric than clergy.

In a sample of retired clergy that Lifeway polled back in 2019, the share who agreed with the statement that their life was ideal was 74%. Which is a bit lower than this result, but only by ten percentage points. I’m pretty confident in saying that clergy seemed pretty content with their station in life (or at least this was the case before the pandemic).

Let’s not stop there, though. Other questions in the National Survey of Religious Leaders can help us get a clearer picture of the mental health and well-being of pastors. There were two questions about how often respondents felt happy and satisfied with life. Here’s how clergy answered those:

Again, there’s some fairly strong evidence that clergy feel pretty good about how things are going in their life. Forty percent of clergy said that they felt satisfied with their life every day and 34% said that happiness was an every day feeling for them. Additionally, another 45% said that they felt satisfied almost every day and 49% were happy almost every day.

In total, 83% of clergy said that they felt happy at least four days a week and 85% said that they had life satisfaction almost every day. In contrast, it was incredibly rare to find clergy who were expressing those sentiments once a week or less. Clergy in that category numbered 3-4% of the sample. It’s just not the case that there were a lot of very unhappy pastors in 2019 and 2020. Just the opposite, really.

So, then I went on this little quest to try and figure out if I could find any factors that may lead to an increase or decrease in life satisfaction among religious leaders. Luckily the survey asked about all kinds of topics. For instance, there’s a question about how many years that they have served in ministry. The average was about two decades. Here’s the share who mostly/completely agreed that their life was close to the ideal, by number of years in the pulpit.

Okay - I think that’s a pretty clear trend line. Clergy who have been in the job for the fewest amount of years are those with lower levels of life satisfaction. About one third who had been a religious leader for less than a decade did not express a high level of life satisfaction. However, among those who had spent four decades leading religious groups, it was incredibly rare to find someone who wasn’t happy with the course of their life. 91% of religious leaders who had at least forty years under their belt mostly/completely agreed that their life was close to the ideal.

How about a different metric now - how many hours that they work per week in their jobs as pastors. I think we can all admit that burnout is more likely when a workload is higher. Maybe that surfaces when looking at life satisfaction.

But, it just doesn’t here. There’s really no relationship between the number of hours worked and the share of clergy who agree that their life is close to the ideal. It was 69% of those who work less than 20 hours a week at their house of worship and it’s 71% among those who are working at least 50 hours a week as a member of the clergy.

One important thing to note is that this survey doesn’t specifically target full time members of the pastorate - there are also bivocational and part-timers in the bunch. But it doesn’t look those who are working lots of hours are any less satisfied with their lives than those who are only doing this is as a side gig.

One more variable that is worth exploration is religious tradition. The team who put together the survey created these categories based on the denominational coding scheme we call RELTRAD - so there are three types of Protestants here as well as Catholics and those from non-Christian faith traditions.

Again, nothing big to report. In fact there is no statistically significant difference between any type of Christian clergy. Catholic priests express just as much life satisfaction as those who are in the mainline, evangelical, or Black church traditions. The differences are less than five percentage points. The only outlier are those who were ministers in non-Christian faiths.

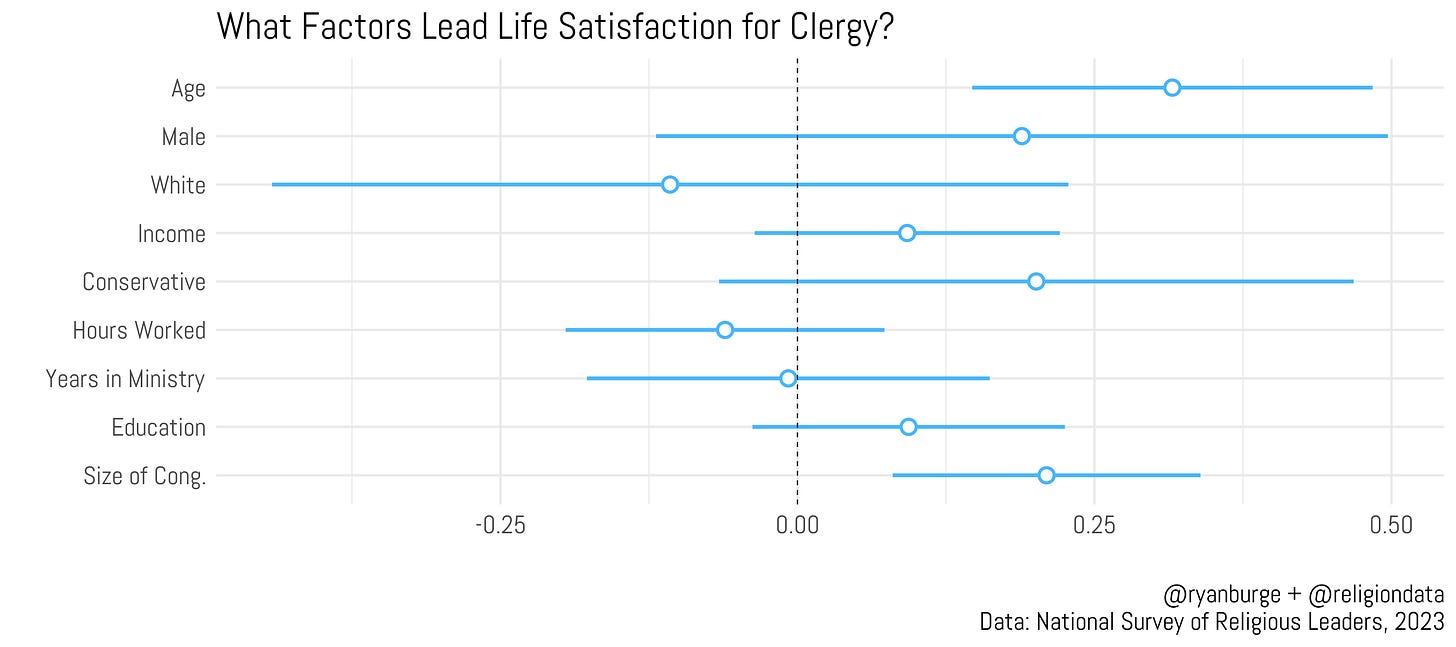

But let’s put this to a more rigorous test - a regression analysis. The thing we are trying to predict is what factors make clergy more/less likely to say that they mostly/completely agree that their life is close to the ideal. I threw a bunch of stuff in this model like age, gender, race, income, education, years in ministry, number of hours worked, political ideology, and size of the congregation at their house of worship.

Most variables in this analysis don’t pop. Things like gender, race, income, and education just don’t matter. None of those things tend to drive life satisfaction in either direction. Neither does hours worked and years in ministry.

There are only two factors that are statistically significant and they both drive pastors to express higher levels of life satisfaction - age and the size of the congregation. Pastors of bigger churches tend to be more content with their lives than those who shepherd smaller congregations. I would bet that’s related to other variables here - like income, education, and number of hours worked.

The other factor, as previously mentioned, was age. Older pastors tend to be more satisfied with their lives than younger pastors, all things being held equal. There’s a well documented finding in the literature - there’s a U-shaped relationship between age and happiness. Those who are very young tend to be happier, then it declines among those in mid-life - usually around 40 years old. But from that point forward, happiness climbs throughout the rest of life.

That may be what’s going on here. Older pastors are more satisfied with the direction of their lives because older people in general express higher levels of life satisfaction.

Of course - the pall over all this data is that it was before COVID. I personally believe that the pandemic had a tremendous impact on clergy. Most of them dodged the land mines of political discourse with aplomb. That wasn’t possible in the Spring of 2020. Masks or no masks? Online worship only or in-person gatherings? Neutrality wasn’t an option in those moments. And the fallout from those decisions are still being felt by pastors, priests and imams four years later.

If you are interested in learning more about clergy’s well being in the post-COVID world, there is some data coming out that topic. A terrific team lead by Scott Thumma has embarked on a project entitled, Exploring the Pandemic’s Impact on Congregations. One report that they published just recently was “Challenges are Great Opportunities: Exploring Clergy Health and Wellness in the Midst of a Post-Pandemic Malaise.” For this interested in the long tail of COVID for those in professional ministry - this is a tremendous resource.

Code for this post can be found here.

I've been a UCC pastor for over 20 years, and anecdotally, it feels like a lot of my peers are feeling tired, burned out, and on the edge. I know quite a few people who have left ministry. Or, they are hanging on to retire soon. Lots of mental health and physical health issues, too. The pandemic seems to have changed the dynamic. Again, this is anecdotal evidence. I wonder if, when reporting about yourself, people feel like they are not "allowed" to be honest. As in, I am being obedient to my vocation, and part of my faith is that my personal satisfaction about ME, doesn't factor in. Or, as time goes on, you get used to this norm that is overworking, stressful, and focused on others, instead of your own happiness.

One possibility not considered here is that some younger pastors who are dissatisfied stop being pastors, which would in part explain why older, more experienced pastors report higher rates of life satisfaction—the satisfied ones stick with it longer.