How Certain Are Clergy of their Faith?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

I was thinking about the act of preaching the other day. It’s something that I did basically every weekend of my life from the time I was 23 until last July. It’s such an odd thing to do in 2025, because how often does the average person just sit and listen to someone else talk for an extended period of time? Speeches used to be commonplace and now they are a relative rarity. Outside of a comedy show or a classroom lecture, it’s just not part of our everyday lives now.

But for a pastor, priest, rabbi, or imam it serves an incredibly important role in the weekly rhythm of their faith community. It’s a time to inspire the congregation to deepen their relationship with God or to understand a sacred text. I’ve found that a number of religious leaders will use this time to project a type of faith that they hope their members will begin to follow. They speak authoritatively and with certainty in an effort to make their flock feel the same way. For what it’s worth, that kind of rhetoric can absolutely inspire some listeners to deepen their relationship with the Divine but I sometimes wonder if it could turn other people away from religion entirely.

A common assumption is that religious leaders get in the pulpit and speak from a deep well of conviction and surety about where they stand on matters of religious belief. If anyone has few if any doubts, it has to be the person leading the congregation, right? Maybe not - at least according to data from the National Survey of Religious Leaders, which is hosted on the Association of Religion Data Archives. The team that put that instrument together included a series of questions that probed how clergy thought about God, the Bible, and various aspects of religious beliefs that offer a fascinating peek behind the curtain into the personal faith of religious leadership in the United States.

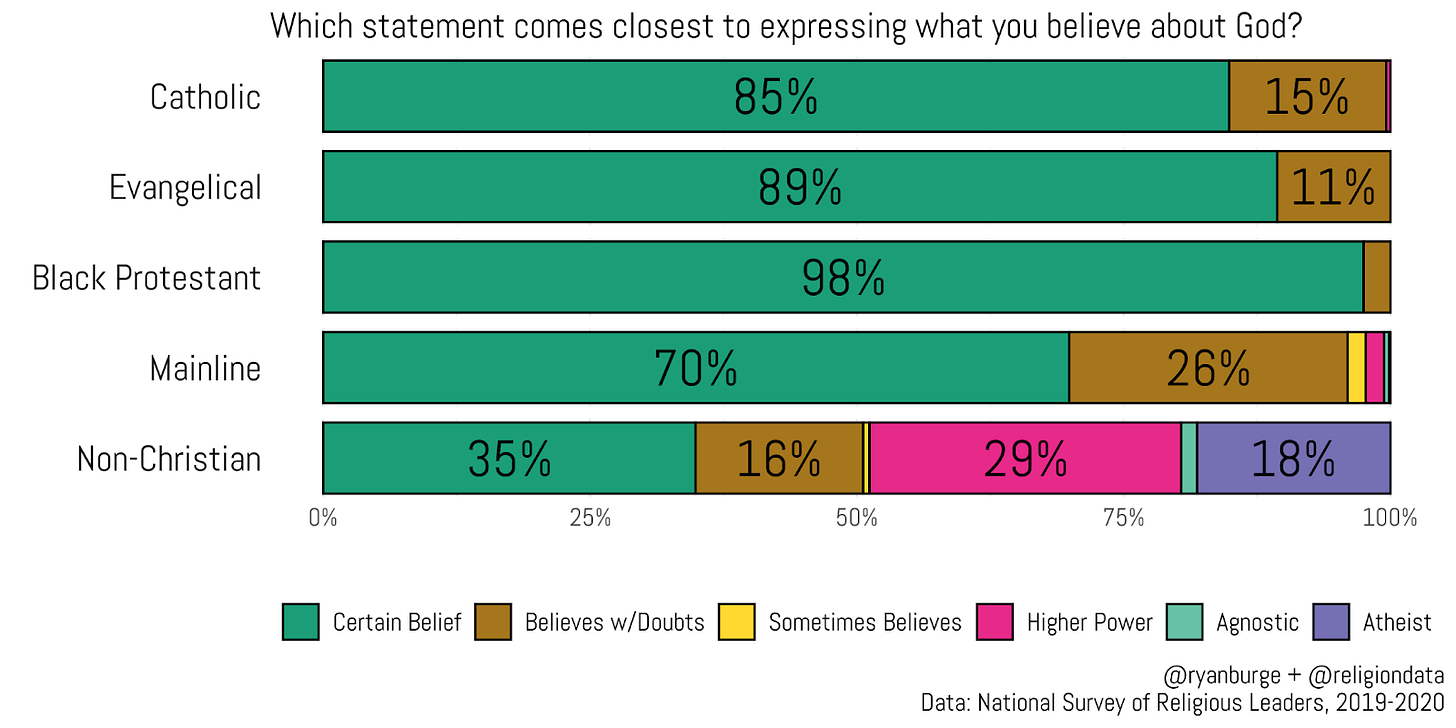

For instance, what about the most basic question - how strongly do clergy believe in the existence of God? Each person was given six possible response options ranging from “I know God really exists, and I have no doubts about it” to “I don't believe in God.” For the record, just 3 Christian respondents in total took an atheist or agnostic position on this question.

However, that’s not to say that there wasn’t a bit of variation when this question is analyzed across religious traditions. For instance, 98% of Black Protestants and 89% of evangelicals expressed a certain belief in God. That was followed closely by Catholics at 85%. The real outlier here were mainline Protestants - just 70% of them expressed a sure belief. Meanwhile, 26% of them said, “While I have doubts, I do believe in God.” That was easily the highest rate of any of the Christian clergy.

The non-Christian sample was really interesting to me, though. About a third of them expressed a sure belief. But another sizable chunk (29%) chose, “I don't believe in a personal God, but I do believe in a higher power of some kind.” But then about 20% took an atheist or agnostic position on this question of God’s existence.

But what about some more specific aspects of theology like the existence of Hell? Or miraculous healing?

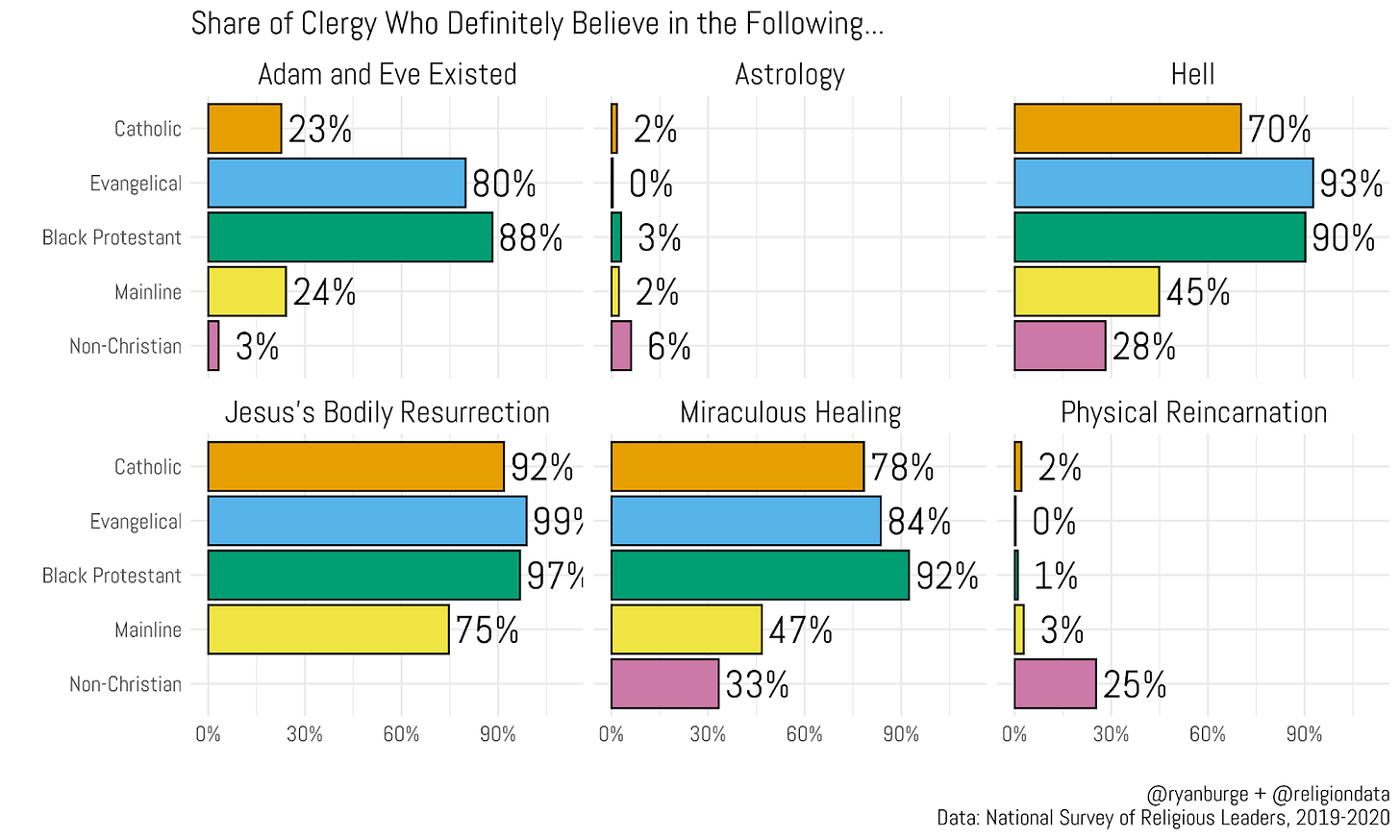

I was pretty surprised to see that the share of evangelicals who believed in Adam and Eve as literal historical people was only 80%, which was slightly lower than Black Protestant clergy at 89%. Meanwhile, Catholic priests and mainline pastors were much lower - with just a quarter saying that they were certain Adam and Eve were real people. What about the bodily resurrection of Jesus? Among Catholics, evangelicals, and Black Protestants - there was a lot of uniformity. At least 90% of them said that this was definitely something that they believed in. For the mainline, the share was still relatively high but a quarter of them didn’t have a certain belief in the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

That’s a consistent pattern in these results, by the way. An evangelical pastor was twice as likely to believe in Hell compared to a religious leader in the mainline (93% vs 45%). Catholic priests were about halfway between, with 70% saying that Hell definitely exists. You can also see this same general pattern on the question about miraculous healing. While 78% of priests expressed a certain belief, along with 84% of evangelical pastors - it was only 47% of mainline leaders.

There were two areas in which I could find a whole lot of similarity among the Christian clergy, though. Almost no Christian pastor or priest definitely believed astrology was real and the same was true for a physical reincarnation. Those seem to be two bright lines among Christian leaders.

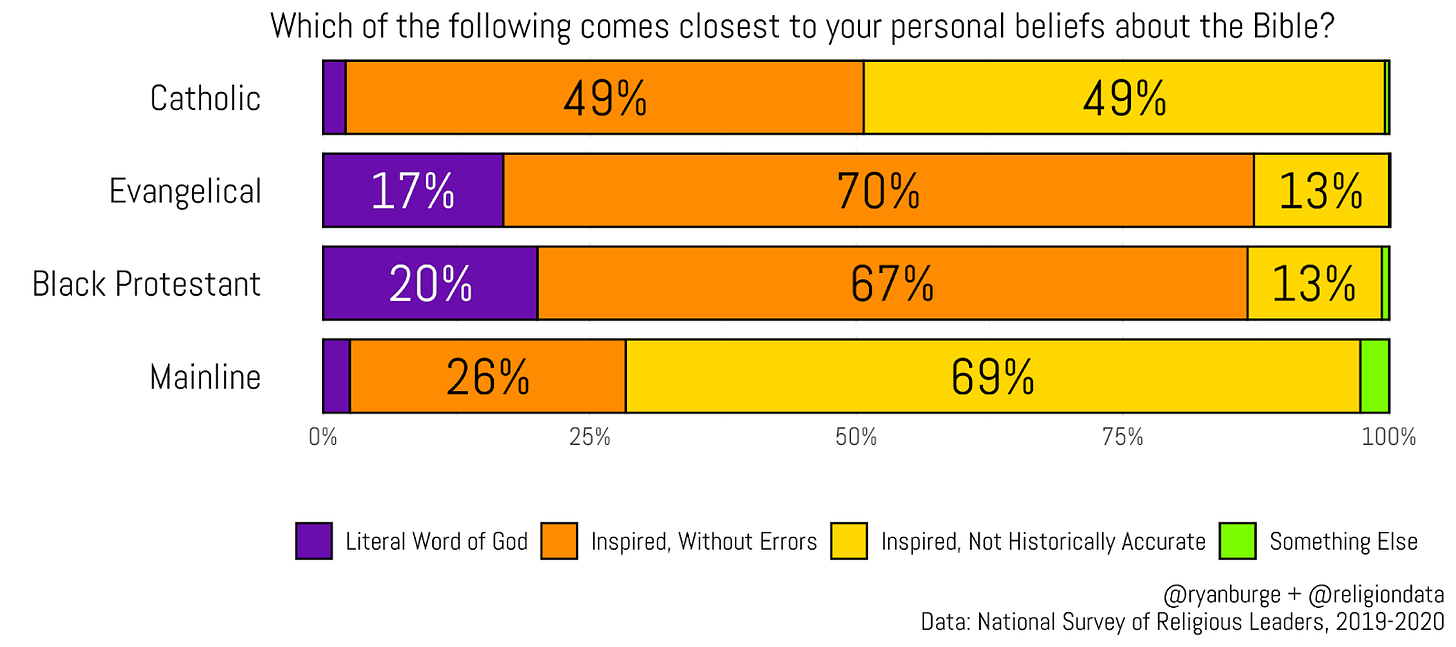

What about belief in the Bible? There were three statements that were chosen by 98% of the Christian sample.

The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word.

The Bible is the inspired word of God, without errors. Some parts are meant to be symbolic, but all of it applies today.

The Bible is the inspired word of God that still speaks to us today, but not all of it is historically accurate, and some parts reflect the culture in which it was written and do not apply today.

However, the proportions of those responses were not equally distributed in each Christian tradition. For instance, about one in five evangelical and Black Protestant pastors chose the “literal bible” option. Before I did the analysis I thought it would be quite a bit higher than that - especially for evangelicals who are often known for their literal interpretation of the Bible. But for Catholic and mainline respondents, almost none of them took a literalist posture.

The most popular choice across the entire sample of Christian clergy was the idea that the Bible was the inspired word of God, but parts of it are really symbolic. Among evangelical clergy, 70% took this position and it was 67% of the Black Church pastors. For the mainline leaders, about a quarter put themselves in that camp. I was struck by the Catholic sample, though. Half of them chose the “inspired, without errors” option and the same share chose the option related to the idea that the Bible is not historically accurate and instead reflecting the culture in which it was written. And, for what it’s worth, the latter position was clearly the favorite among the mainline pastors - chosen by 7 in ten of them.

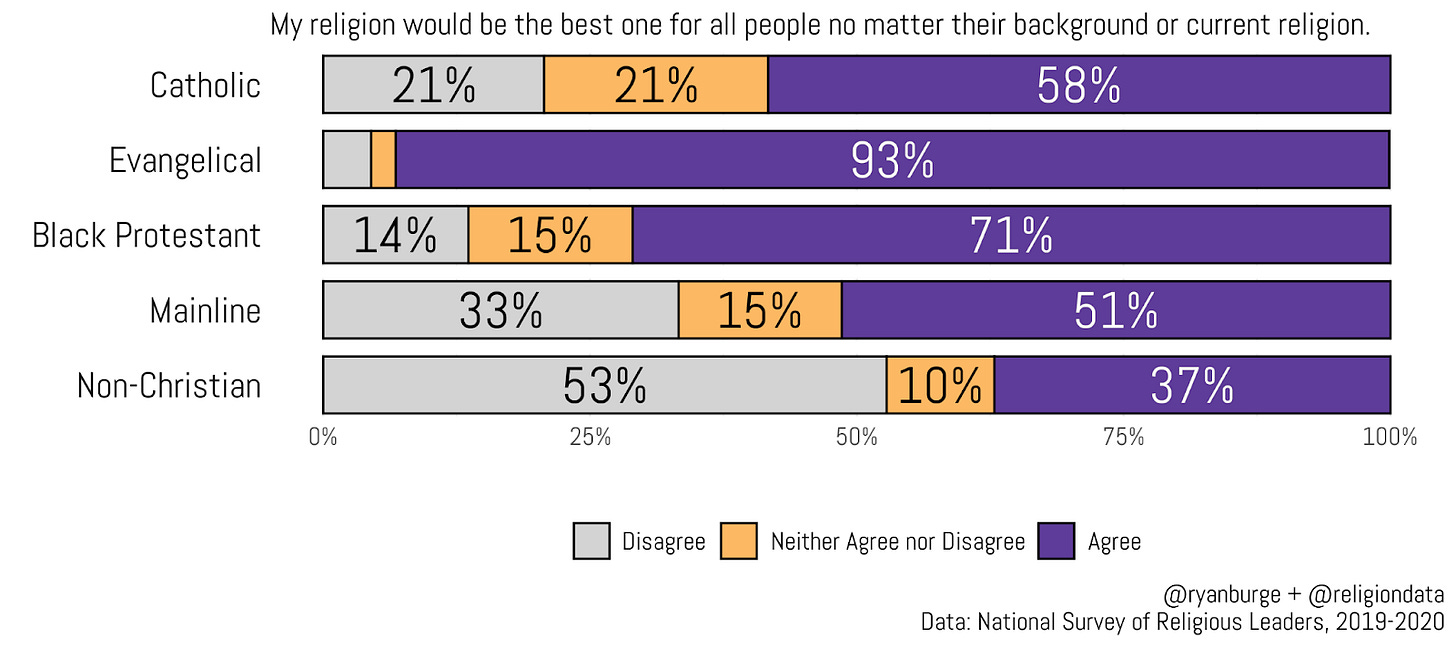

I think a lot of these previous questions were trying to get at a pretty important concept - how certain clergy are of their religious convictions. Asking about their understanding of God, miracles and Hell can be a good way to do that. But there’s another way, too - by asking them if they think that their worldview is superior to other perspectives. There’s a statement in this survey, “My religion would be the best one for all people no matter their background or current religion” that really gets to the heart of the matter.

This is a great example of how the evangelical understanding of religion differs from other faith groups. In this sample, 93% of the evangelical pastors said that their religion was the best one for all people. That was 22 points higher than Black Protestants. It was also significantly higher than Catholic priests and mainline Protestant pastors. For the Catholics, 58% thought that they had a superior perspective and it was a bare majority of the mainline at 51%. I do want to note that the non-Christian clergy had a much different approach here - a majority disagreed that they had a superior worldview.

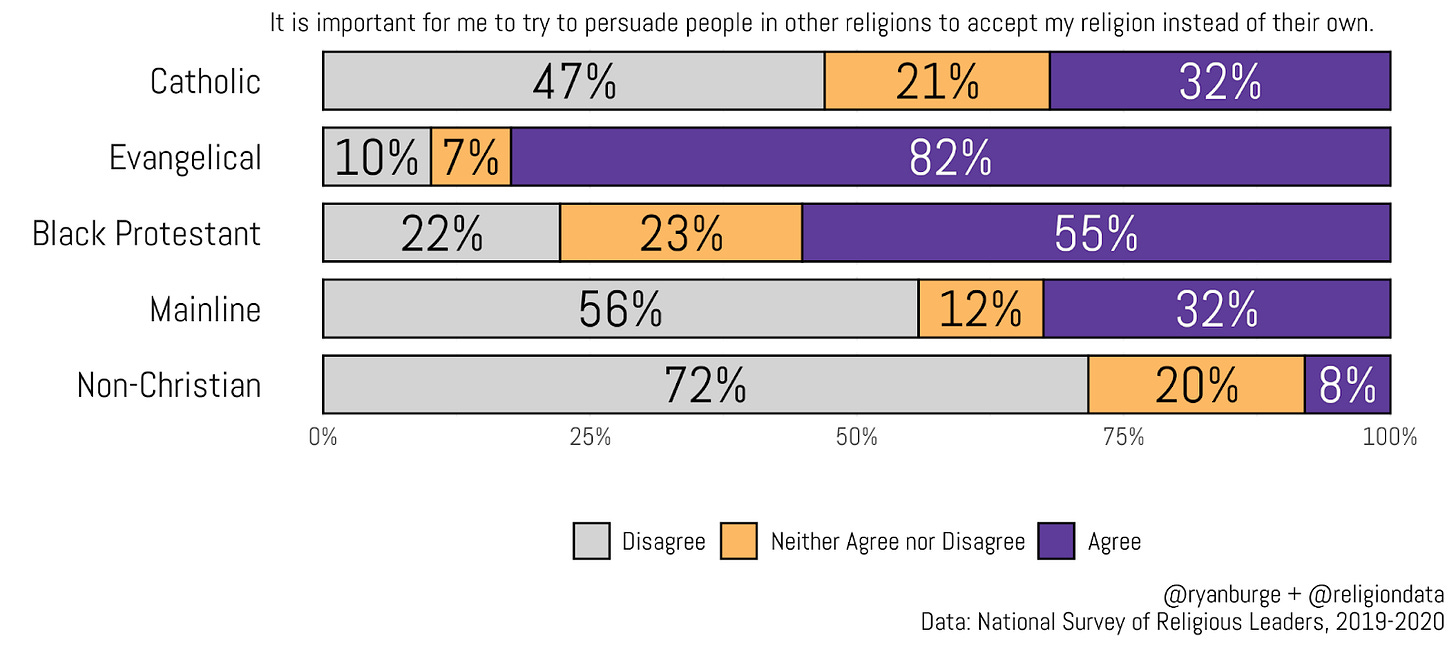

There’s another question that even takes this a step farther - it asks about evangelizing to other faith groups. The statement is, “It is important for me to try to persuade people in other religions to accept my religion instead of their own.” It’s one thing to believe that one has a monopoly on the truth, it’s another matter entirely to want to convince other people of this fact.

Again, evangelicals stand apart because they really do take religious conversion seriously. In this sample of evangelical pastors, 82% of them put a great deal of emphasis on persuading people in other religions to accept evangelical Christianity as their own. That’s fifty points higher than Catholic priests or mainline pastors. I think this graph and the prior one does an excellent job of illustrating how distinct evangelicalism is even inside American Christianity. It’s certainly a faith tradition that seems much more certain of its beliefs than leaders in other faith groups.

And speaking of other faith groups, religious leaders of non-Christian traditions seem almost completely allergic to the idea of trying to convert other people. In this survey, 72% of them disagreed with the idea of evangelizing others and just 8% agreed. There’s a lot to consider here in how minority faith traditions have a different idea about trying to proselytize to folks outside the faith.

Are clergy paragons of strongly held and unshakeable beliefs? I don’t know if that’s the case, really. It does seem true that evangelical pastors have a great deal of certainty about God and the Bible and other theological matters - a finding that is largely replicated among Black Church pastors, too. But the average Catholic priest or mainline pastor is consistently less strident than their evangelical cousins. Doubt seems to play a large role in these two Christian traditions.

And, as I mentioned previously, that’s probably a feature of American Christianity, not a bug. Some interested people may feel drawn to the existential certainty found in a lot of conservative Christian churches, while others may feel more at home in a church where the pastor openly struggles with doubt. As Finke and Stark made plain in their magnum opus - a diverse religious marketplace offering a wide array of religious beliefs and practices probably appeals to a broader proportion of the population than a religious landscape with just one option.

Code for this post can be found here.

Some thoughts:

1. The “word for word literal” vs. “inspired but parts symbolic” question is poorly worded. You’re probably thinking about things like Genesis 1-11. But I know people who would consider Genesis 1-11 to be completely literal history yet would still agree the Bible is partly symbolic, because of the Psalms and so on. The Adam and Eve question gets closer to the real answer.

2. For Roman Catholic clergy, I think the only point here with surprisingly high support that disagrees with Catholic doctrine is the denial of hell. On the question of Scripture having errors, I believe the Catholic doctrine is there might be minor historical errors (e.g. the size of the armies in Joshua) but the core of the historical narrative is all true.

3. Psychologically, the seeming lack of faith among Roman Catholic clergy compared to evangelical or black Protestants is interesting, when they have given the most up. But maybe for that reason it’s also the hardest to leave? I would also guess that there’s a generation gap here, with older Catholic priests harboring more doubts.

EDIT: I realize I was mistaken on this point about hell -- best I can tell universalism is accepted as a valid opinion within the RCC.

At least for the Catholic clergy respondents, it’s worth noting that the most “strident” response does not necessarily reflect the Catholic Church’s authoritative teaching, or the statements may be ambiguous because they’re not written in theological language. For example, on the Biblical question that you highlight, a Catholic could likely affirm both (2) and (3) based on completely orthodox doctrine, e.g., regarding the New Covenant.