What is the Role of the Chaplain in the 21st Century?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

Whenever you hear the word “clergy” what comes to mind? I would hazard a guess that it’s probably the pastor or priest of a local church. They preach each Sunday, do some visitation, lead some Bible studies, and also help organize community outreach activities. But there are lots of clergy who don’t actually serve in a traditional role in the local church. Instead, some work in denominational offices, and others are directors of parachurch ministries. But another significant role for paid clergy is being chaplains.

While it’s hard to come up with a clear estimate of the total number of chaplains in the United States, the United States military reports about 3,000, and according to one study, the average hospital has about 2.5 FTE chaplains per 100 patients. That means a larger hospital could have a dozen on staff at any given time. It’s safe to say that chaplaincy is not as widespread as local church pastors - but they can play a significant role in the spiritual life of Americans.

It’s also an understudied topic from a data perspective. That’s why I was glad to see that Wendy Cadge, a terrific sociologist and new President at Bryn Mawr College, had been awarded a grant from the Templeton Foundation to study how the public perceives chaplains. The end result of that was a book entitled Spiritual Care: The Everyday Work of Chaplains, which was published by Oxford University Press in 2022. Dr. Cadge was kind enough to also share that survey data with the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA).

I found the results to be fascinating.

Let me just start by using the key metric in the survey - the percentage of Americans who have ever had any interaction with a chaplain.

According to this data about two-thirds of the general public have never encountered the work of chaplains. That means that just about a third have interacted with the chaplaincy. What is also striking about this is how almost none of those encounters were done through online communication. Just 2% of the sample indicated that they had visited with chaplain virtually alone or had virtual and face to face interactions. It seems like this is a part of the ministry that has either not embraced the new era of communication technologies or ministers in such a way that their work is not easily transferable to the virtual world.

I wanted to try and sort out what factors made someone more or less likely to have any contact with a chaplain. What makes this kind of work difficult from a methodological perspective is that while the survey was a random sample of 1,096, only 335 of them answered yes to the prior question. Which means that oftentimes subgroups can represent an even smaller part of the United States population.

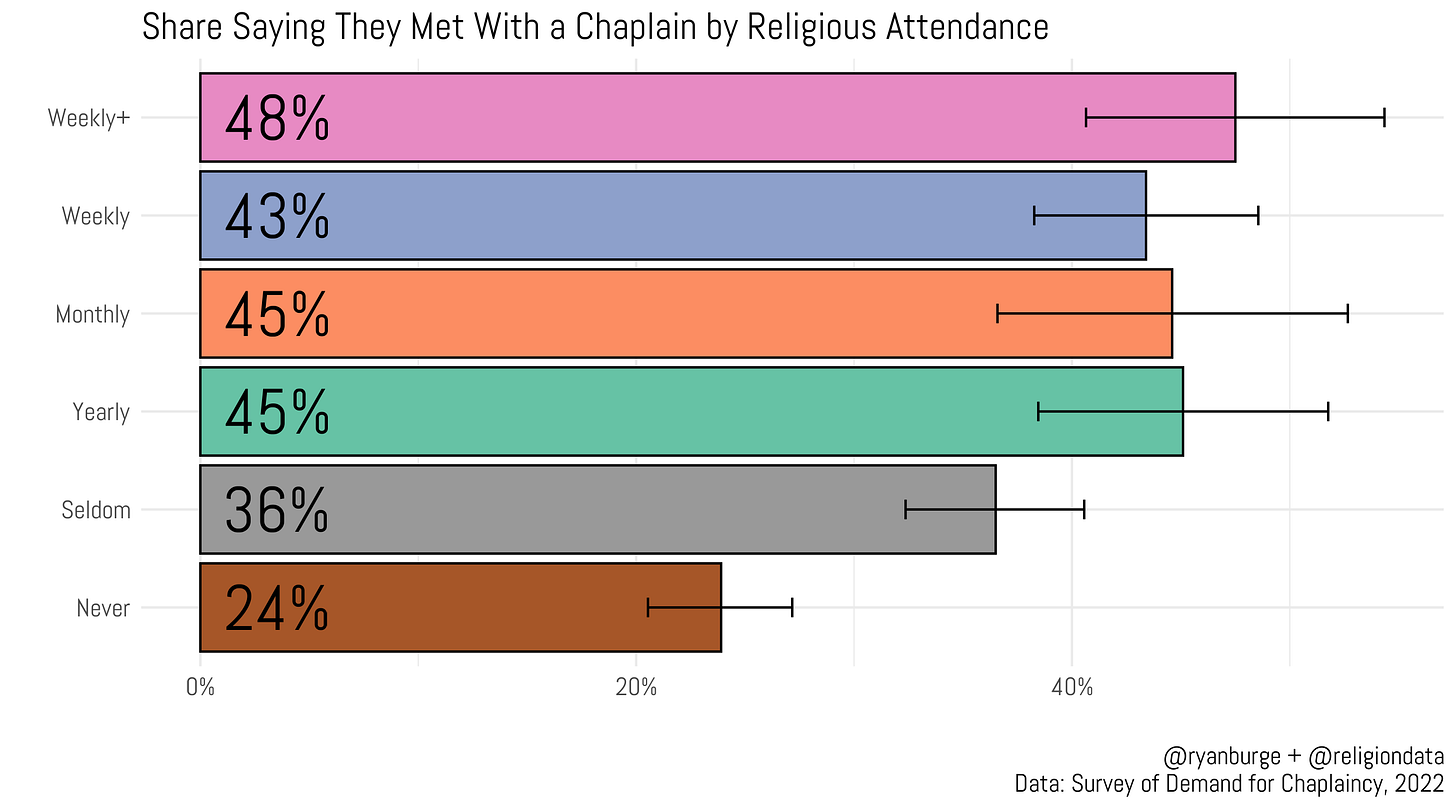

That becomes clear when looking at the confidence intervals when the sample is subdivided by religious attendance. Although I do think that the data points to the unmistakable conclusion that people who never attend religious services were significantly less likely to indicate that they had any communication with a chaplain. As religious attendance climbs, so does the likelihood of speaking with a chaplain.

What does strike me, though, is how little difference there is in the top four categories of attendance (yearly through more than once a week). In each case, the percentage who had met with a chaplain was about 45%. Apparently there’s a clear line of demarcation: the never/seldom folks versus everyone else.

What about self-described religiosity?

It should come as no surprise that the same general gradient that emerged in the prior graph also appears here. The folks who were the least likely to have any interaction with a chaplain are those who said that they were ‘not at all’ religious. But as self-described religiosity increased, so did familiarity with chaplains. Among those most religious, about 45% reported some experience with a chaplain. It is striking how no category here had a clear majority, though.

Considering only about a third of Americans have ever had any communication with a chaplain, how did that connection get made? Well, the survey asked about that.

It is pretty interesting to note that the most likely means for a connection to be generated between the public and a chaplain was when the chaplain initiated the encounter. This was the case 44% of the time. In contrast, 29% of the sample said they had personally requested a chaplain in their time of need. The only other arrangement that showed up with any frequency was when the individual said that someone else referred them to a chaplain.

I think one clear conclusion from this data is that chaplains need to be very intentional about trying to make connections with people in their time of need. In this data, just 30% of folks who had a relationship with a chaplain did so through their own personal initiation. This seems like a situation where the most frequent outcome is when the chaplain makes the first request.

When the connection is established, however, the individual and the chaplain discuss which topics? The survey included a nice battery of options ranging from dealing with change to the meaning of life.

I was struck by the fact that there’s no clear example of a topic that was brought up in the vast majority of relationships between chaplains and the general public. A couple topics were around the 50% mark, though. They include dealing with change, reading passages from religious texts, mental/emotional health, and family dynamics.

It was interesting to note that questions about death and dying and dealing with loss were not that prominent. In fact, those topics only appeared among 44% of respondents in this sample. Other issues that weren’t discussed with a lot of regularity were ‘the meaning of life’, ‘relationship issues’, and the physical health of the respondent.

It was noteworthy, though, how these conversations with chaplains really covered a whole lot of ground. It wasn’t always about death, it didn’t always concern mental health, and it doesn’t look religious topics were being discussed in a significant number of these encounters, either. From this angle it looks like each of the meetings between chaplains and the public are incredibly unique and really tailored to the specific circumstances of each situation.

But do those who have a relationship with a chaplain feel like it was a good use of their time? There was a section of the survey that asked folks if the chaplain that they dealt with had certain characteristics like compassionate or pushy.

The most evident conclusion from this survey was that when people deal with a chaplain they almost universally report that it was a good experience. Over 90% of folks said that their chaplain was compassionate, a good listener, trustworthy, spiritual and knowledgeable. For chaplains taking a look at this data, this should be a digital ‘pat on the back.’ The job approval rate of chaplains is incredibly high when looking at the responses to these questions by folks who had a personal interaction with one.

Almost none said their chaplain had negative characteristics. Just 10% of folks said that their chaplain was intrusive and only 7% said that their chaplain was pushy. Again, this data makes this point plain - when people have a relationship with a chaplain it is almost always a positive outcome.

There are other questions that point to this same conclusion. For instance, among those who had dealt with a chaplain - 74% said that it was more helpful than harmful and only 5% said that it was a negative experience, on balance. It would be hard to find a profession where only one in twenty folks would say that they have a negative impression of that line of work.

For the average person, experiencing a loved one's medical crisis is not a common occurrence. Thankfully, for most of us, it may only happen a handful of times. However, what that often means is that many of us are not psychologically prepared for dealing with difficult questions about life-saving techniques and end of life care. In contrast, chaplains have seen similar situations hundreds of times and receive training for these times of need. Many times during the course of my pastoral ministry I turned to a local chaplain to help me guide a church member or their family through these rough waters.

According to this data, those who interact with a chaplain almost always have a positive experience. As religion continues to decline, one has to wonder if this will further thin the ranks of chaplains in the United States. And this raises an important question: If those folks disappear, who will bear those burdens for families in need?

Code for this post can be found here.

32-year-old hospice chaplain here. Thanks for writing

Thank you for writing about chaplaincy! I'm a Presbyterian minister whose entire ministry has been hospital chaplaincy and now run a Spiritual Care Department at a large Level 1 Trauma Center and teach chaplaincy training programs (Clinical Pastoral Education). I often write and speak about chaplaincy in an effor to raise awareness about our vocation and how helpful we can be. Our field has a marketing problem in that many people don't know what a chaplain is or does!

I'm so grateful to Wendy Cadge for being an awesome advocate and chaplaincy researcher. Just a note about the research - the majority of people who we are discussing end-of-life issues with or providing support to while are dying would be unable to fill out a survey, so that will have likely skewed the data. We encouter the same issue in the hospital, where patients who die - of course - cannot fill out surveys, so often the work that we do with them and their families goes unreported/researched.