American Clergy in Colonial America

A peek into American religious history from 1763-1783

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

And now for something completely different!

I spend a lot of my time on this Substack providing analysis of survey data, which makes sense because I am a social scientist and all. I think that’s the primary way that most of us are introduced to the world of data analysis - we are given a link to download the GSS, pointed toward the codebook, and told to get to work.

But there’s all kinds of other data out there that can help us understand the world around us. I’ve tried to do a bit of that in a few posts. I wrote about the content of resolutions adopted by the Southern Baptist Convention. The average pay of a member of the clergy. And the enrollment trends in a bunch of Christian colleges and universities.

Well, the ARDA posted an absolutely fascinating dataset called Clergymen in Revolutionary America (1763-1783). It’s exactly what you think it is - a big spreadsheet of clergy in the Colonies. That’s awesome. The data comes as a result of the efforts by Lewis Frederick Weis in the 1930s to collect this information. It resulted in the publication of two books The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of New England and The Colonial Churches and the Colonial Clergy of the Middle and Southern Colonies.

The summary of the data is as follows:

Weis listed every colonial minister, along with the church or churches pastored by that minister between the founding of Jamestown and the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, although this dataset is limited to the Revolutionary era (1763-1783). Weis also listed the location of the churches, the ministers' years of service, educational degrees held by the minister, and their denominational attachments.

The reason that the ARDA has this data is through the efforts of David Clemons who digitized those earlier records as part of his dissertation project.

There’s not a ton of variables here, but I think this offers a fun little peek into the world of colonial religion through the lens of 4,156 clergy records.

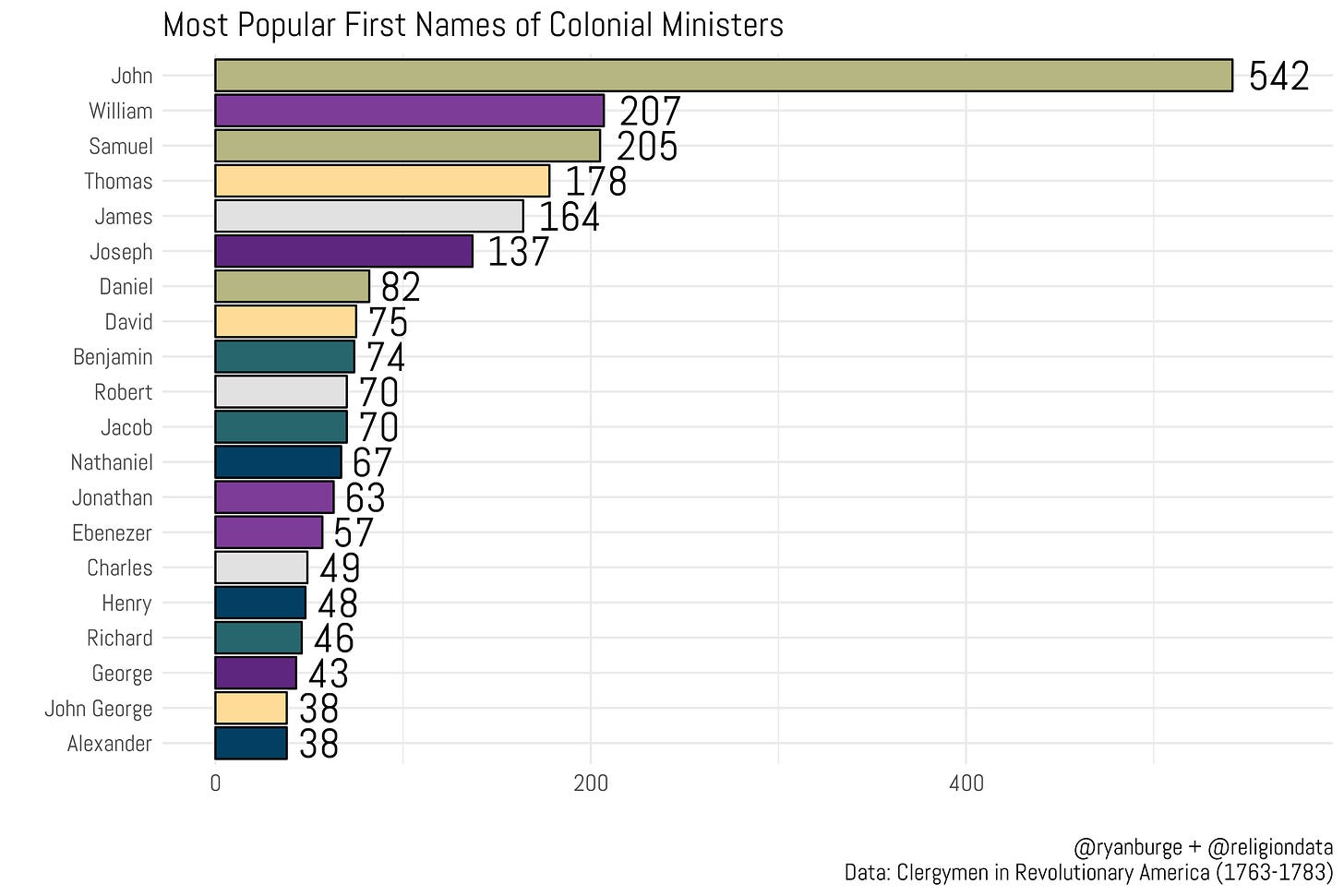

For instance, the ministers are listed by first and last name. If you just count the most popular names what you find is that there are a TON of Johns in this data. In fact, 13% of all ministers had that name in this data. And that doesn’t even include the Jonathans and John Georges that also appear. But I do think that you can clearly see that these names have a lot of commonalities. They are pretty typical of names of folks who come from places in Northern Europe. You don’t see Jacques, Tomás, or Dietrich in the list. A lot of these folks are English or come from English ancestry.

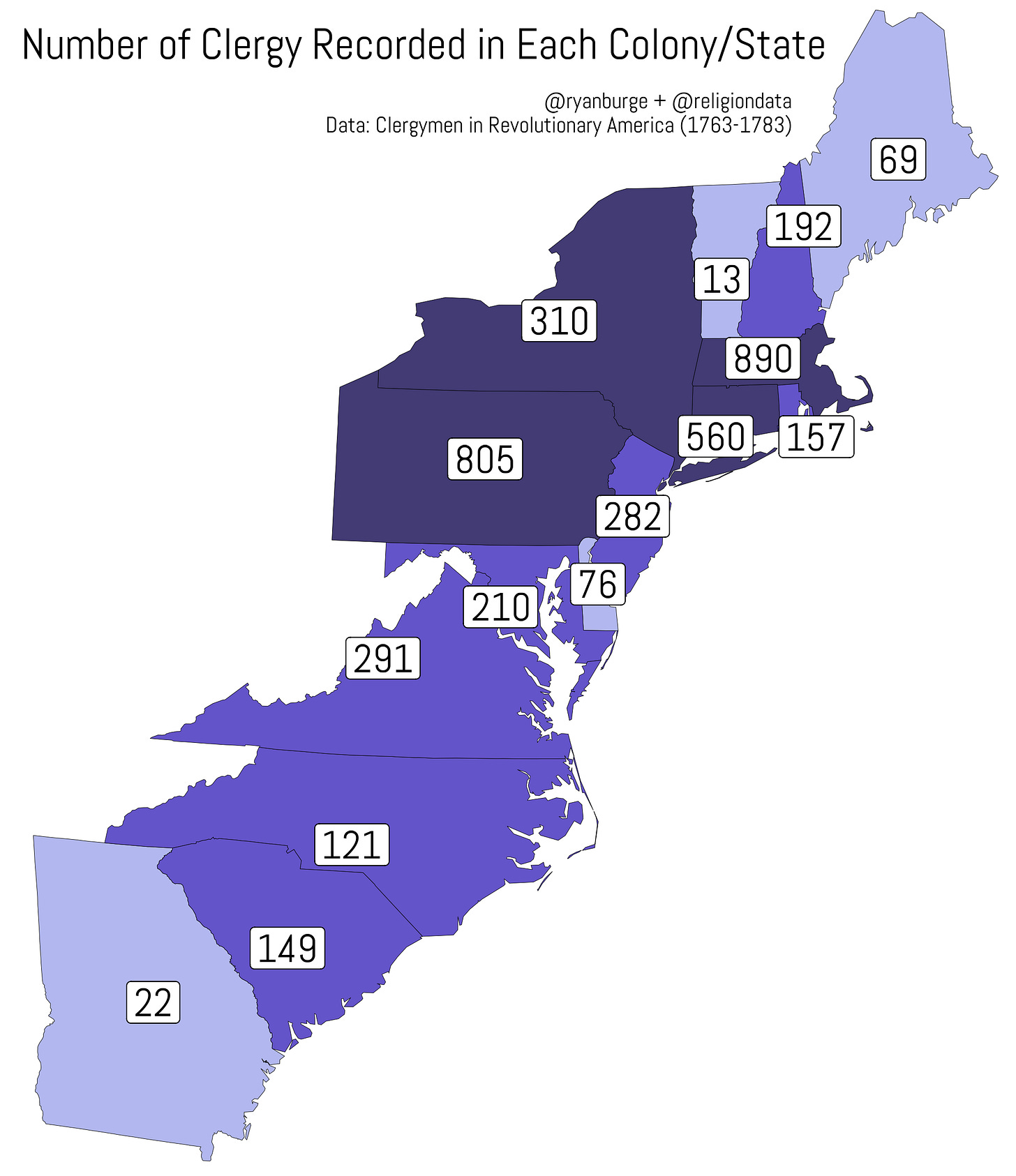

But there is also geographic data in this collection, too. That means I can get a good sense of where these clergy were located in the colonies. (By the way, I strongly recommend you check out these interactive maps at the ARDA. If you want to get a sense of how American religion has changed geographically, it’s a tremendous resource.)

There were a lot from the state of Massachusetts - over 21%, in fact. If you add in Pennsylvania, that’s over 40% of all of the clergy listed. Other states that show up a lot are in the northern colonies. There are many clergy from Connecticut, and New York, too. What is striking to me is how the dataset contains nearly 200 members of the clergy in New Hampshire, yet there are just 13 pastors from the state of Vermont. In comparison, there are 157 from Rhode Island. Definitely some inconsistencies there in terms of population size to clergy ratio.

There are far fewer records of clergy in the southern colonies. For instance, just 291 Virginian clergymen appear and it’s 270 from the Carolinas. If one thinks about the locus of religious influence during this time period in American history, this data points to a more northward tilt. That’s clearly different from how we think about religion today.

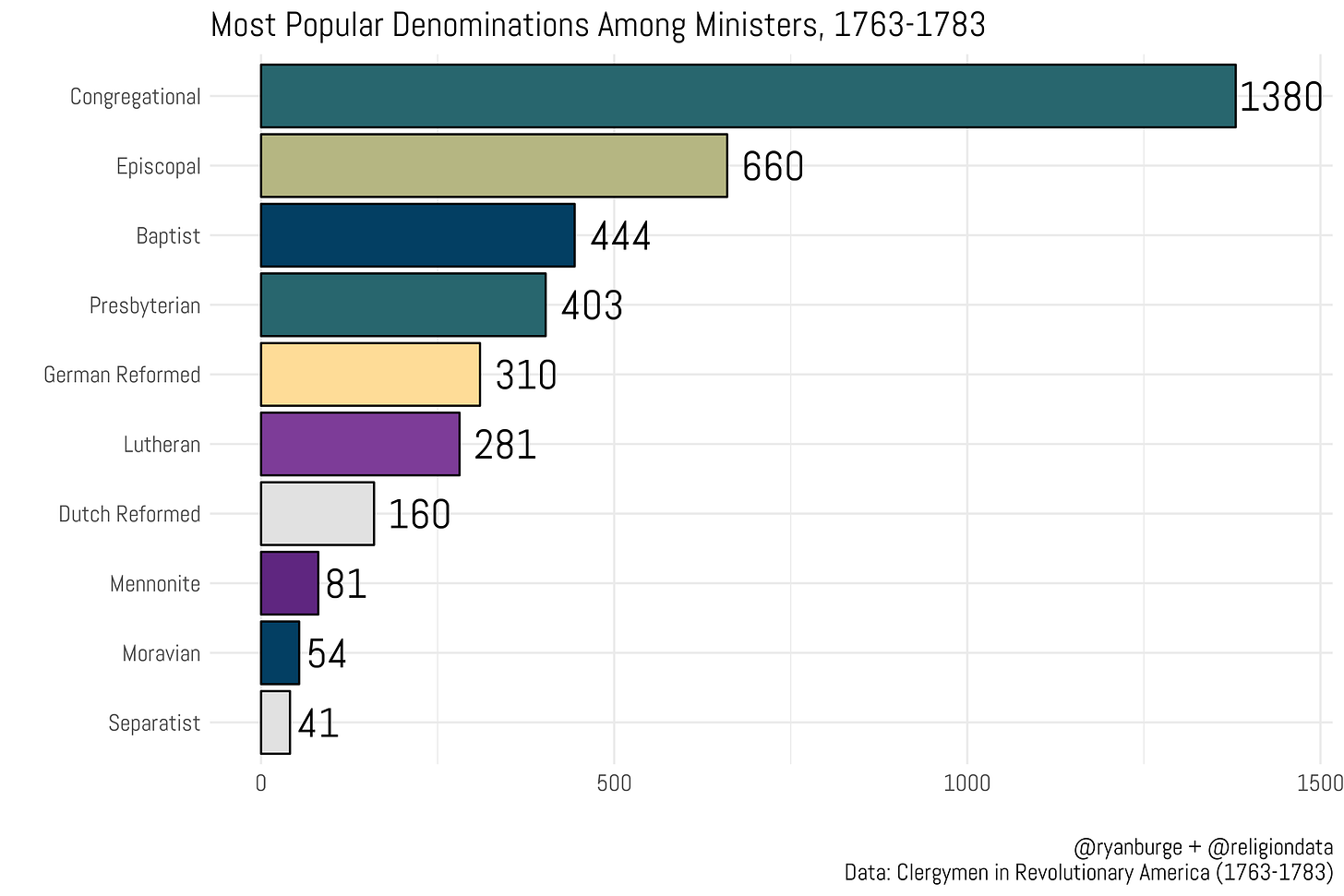

What about the denominations that show up the most? This gives us a fascinating look at religion during this crucial period of American history.

Without a doubt the Congregational church dominated American religious life during the 1760s-1780s. I’m sure that a few readers are asking themselves a simple question: what is a Congregationalist? Which tells you a whole lot about how much religion has changed in the United States.

The answer is that Congregationalism finds its roots in Puritanism (which was the faith tradition of the Pilgrims). Theologically, the Congregationalists were Calvinists but organizationally they look a lot like Baptists - a clear focus on local church autonomy. If there’s any through line in Congregationalist worship its a strong rejection of anything to do with the Church of England. No more clerical vestments, no organs, no kneeling. The definition of what we would call “low church.” If you are looking for the remnant of Congregationalists in the United States it’s the United Church of Christ. The UCC reported 2.1 million members in 1962. It has 700K today.

The second most popular was the Episcopal Church at 660 clergy followed by Baptists and Presbyterians. But also take note of how many traditions on this list don’t really exist in large numbers anymore: German Reformed, Dutch Reformed, Moravians, and Separatists.

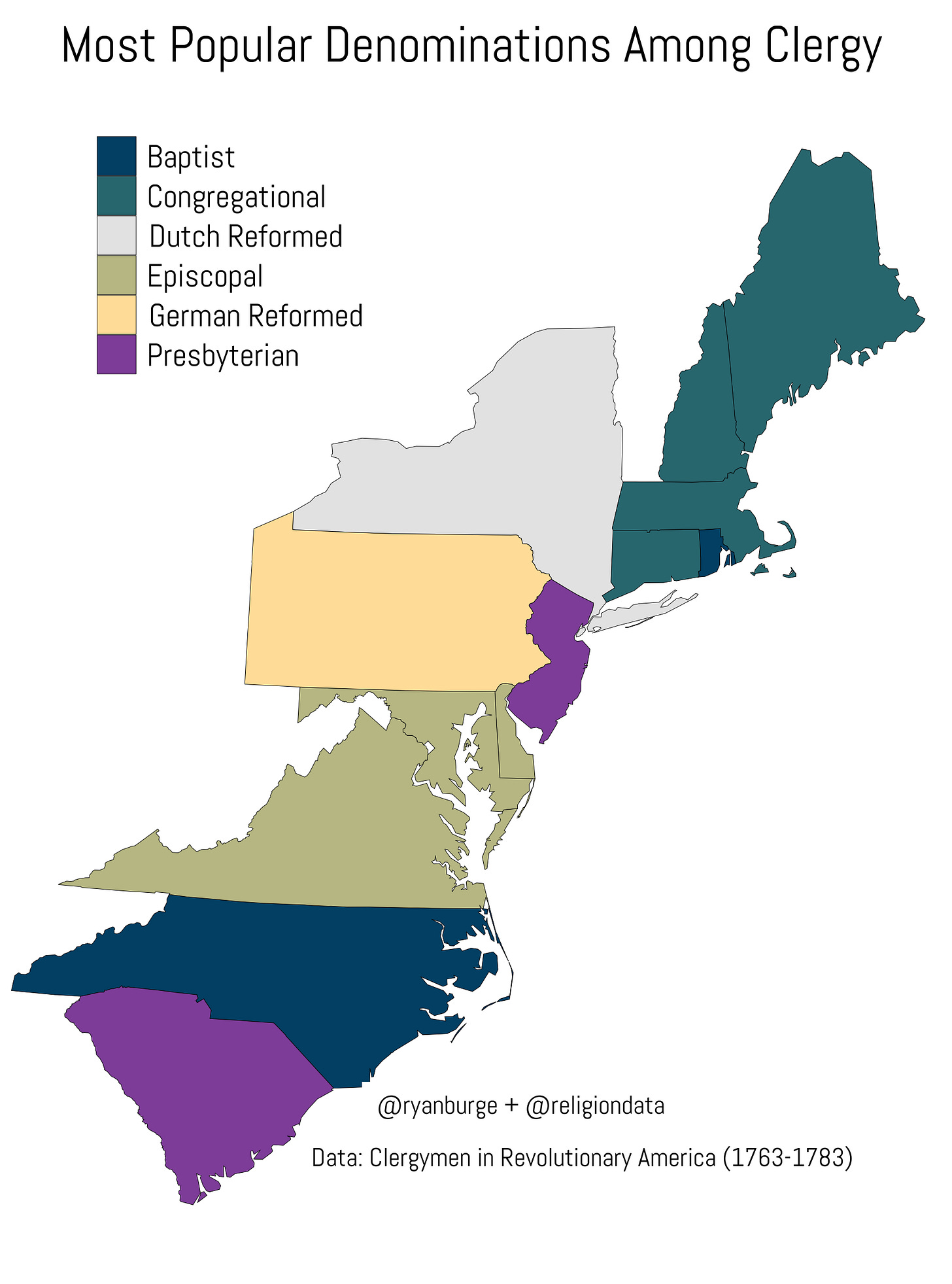

How about we break these denominations down by state, though? That can give us a sense of geographical concentration.

The Baptists lead the way in two states: North Carolina and Rhode Island. This is the part where I tell you that Roger Williams founded the first Baptist church in the New World in 1638 in Providence, Rhode Island. It’s still in operation, by the way. But Rhode Island was an aberration in that part of the world. Instead, Congregationalists dominated in the northeast. Other reformed traditions could also be found in New York and Pennsylvania. The Presbyterians were plentiful in an odd combination of states: South Carolina and New Jersey. The Episcopalians held sway in the middle part of the Colonies in Virginia, and Maryland.

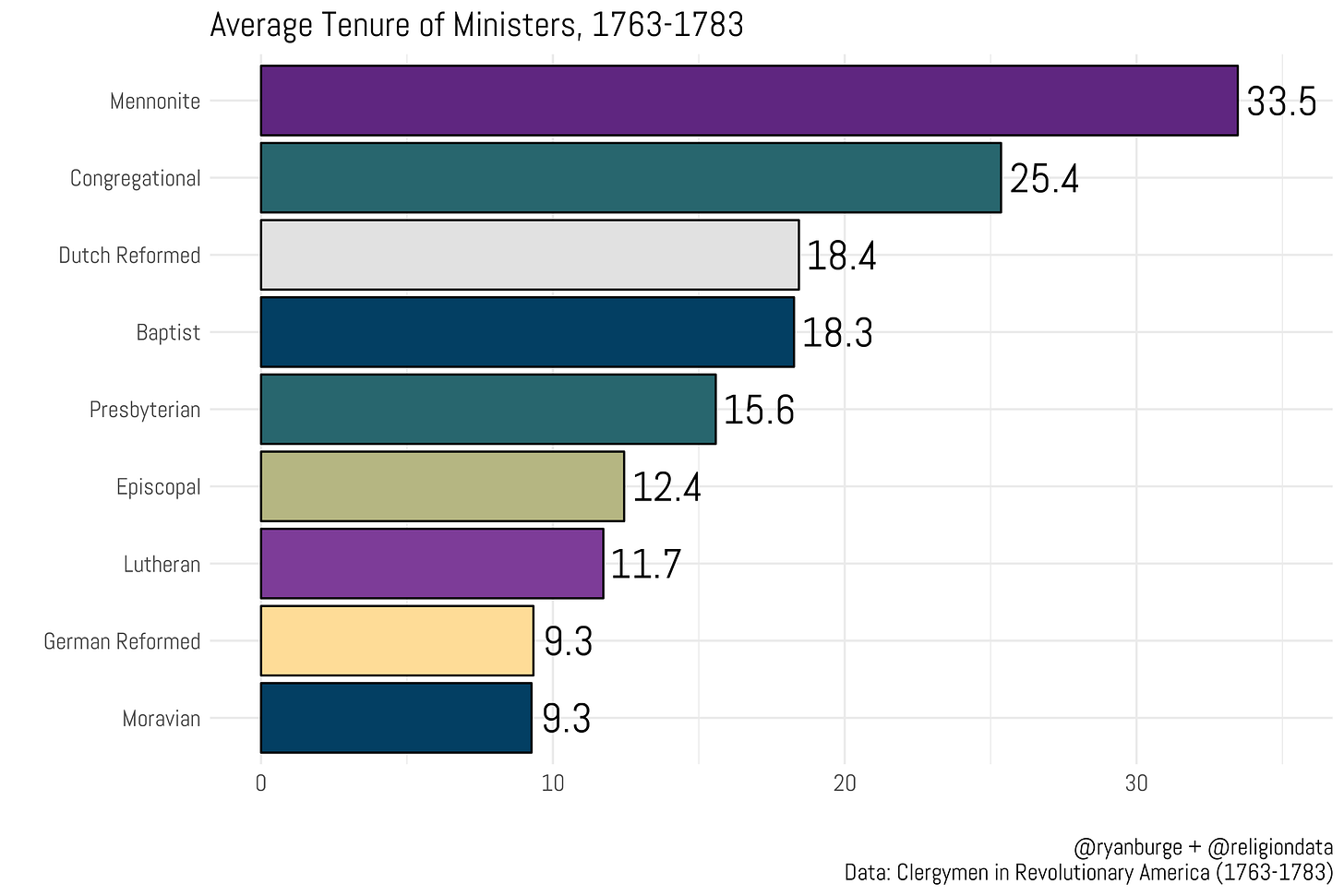

There’s also another interesting little tidbit in this data - the year the pastor took over at a church and the date which they left. That means I can calculate pastoral tenure with a fairly high degree of accuracy. I tried to find an answer to the question of average length of stay for a pastor in contemporary America and couldn’t find a consistent answer. It seems like it’s somewhere around five years. Pastors in colonial America served much longer terms.

For instance, the average Mennonite minister in the data was around for 33 years. That’s basically an adult lifetime for men during that time period. But Congregationalists pastors also stuck around for a long time, too - 25 years, on average. In fact, it was really rare to find a pastor in this data who wasn’t at his church for at least a decade.

I think we can all find a myriad of reasons for why this was the case. It was probably harder to hear about other churches needing pastors in those days, so it was logistically challenging to find open pulpits. Pastors in lots of these congregations were also well respected and influential, too. That makes it easier to stick around. And part of it could be even simpler - book keeping. Maybe a pastor who didn’t last that long was never entered into the records that Weis collected for his two books.

It’s always fun to analyze data that is not the typical stuff. It makes me think a lot about the world of colonial religion and how much things have changed over time. We undoubtedly had a lot of Christians in this country during the Revolutionary Period. I frequently wonder if we plucked one of those Christians out of their time period and dropped them into the 21st Century American landscape, if they could make any sense of things. Some things have not changed, but many clearly have.

Code for this post can be found here.

Re: New Hampshire compared to Vermont, it's worth noting that New Hampshire was widely settled by the period in question (my ancestors founded the town of Peterborough c. 1730, for example). Vermont, by contrast, wasn't settled until the latter half of the period covered by the dataset, which explains the dearth of clergy.

I note as an addendum that some of the old German Reformed churches here in Pennsylvania are still around, they've just been folded into the United Church of Christ. I attend one that was founded GR in the 1700s, joined the Evangelical & Reformed in the 1800s, then merged with the Congregationalists to become UCC in the 1950s. That seems to be a common story around here, and I assume it's why Pennsylvania has more UCC churches than any other state.