Religion as a Cultural Identity (Part 2): The Surprising Reality of “Cultural Judaism”

Maybe there are three types of Jews

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

Before diving into the graphs, I should note that this is really the second post in a two-part series on religion as a cultural identity. I’d strongly recommend going back and reading the first post to get up to speed on a set of questions from the Pew Religious Landscape Survey (hosted on ARDA). Those questions are designed to dig more deeply into the idea of cultural Judaism and Catholicism.

Here’s a quick overview of how the survey works. Respondents were first asked the standard question: “What is your present religion, if any?” They were given about a dozen response options, ranging from Protestant to Catholic to Jewish to agnostic. After answering that question, respondents were given a follow-up battery that asked: “Aside from religion, do you consider yourself to be any of the following in any way (for example, ethnically, culturally, or because of your family’s background)?” The options included Jewish, Catholic, and several others.

Importantly, if someone had already identified as Jewish in the standard religious affiliation question, they were not allowed to also answer “yes” to the follow-up question. That means we can use these items to distinguish between people who are religiously Jewish and those who are culturally Jewish—and do the same breakdown for Catholics.

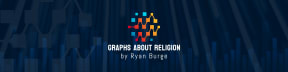

Here’s what those percentages look like in the full sample.

We can see that about 19% of American adults selected Catholic as their religious affiliation in the first question. That lines up well with a wide range of other datasets that estimate the share of Americans who identify as Catholic. But here’s what’s more surprising: about 12% of respondents did not say they were Catholic in that first question, yet still answered “yes” to the item about cultural Catholicism. Put differently, roughly three in ten American adults are Catholic in one way or another. For context, that’s a larger share than the non-religious.

When it comes to Jewish identity, the percentages are much smaller. In the full sample, 1.7% of respondents said that Judaism was their present religious affiliation—right in line with widely accepted estimates. In fact, I pegged the number at about 1.5% in my book, The American Religious Landscape. But here’s the surprising part: an additional 3% of Americans said that they are culturally or ethnically Jewish. Does that mean that nearly 5% of the U.S. population is Jewish? Not so fast. Let’s look at that claim a bit more carefully.

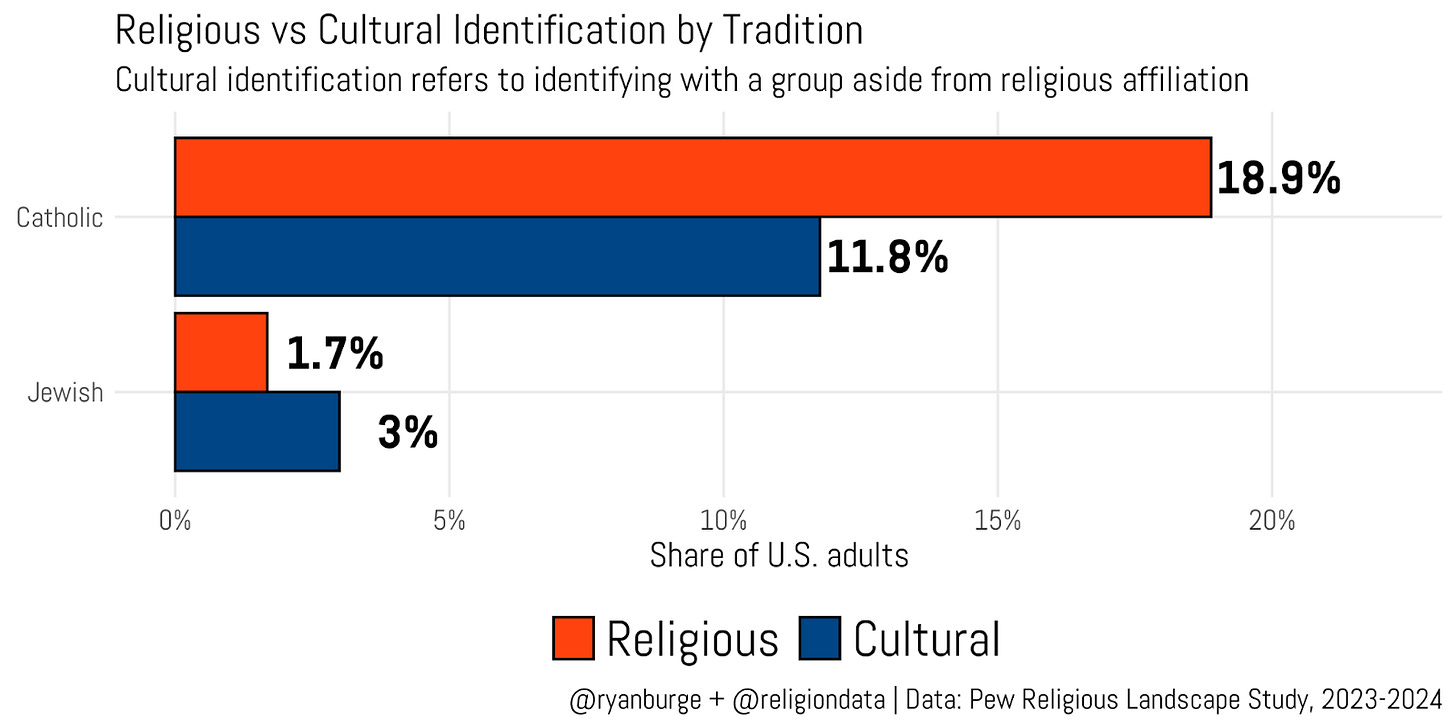

When I first saw these numbers, my initial thought was that cultural Jews and Catholics are likely people who grew up in those traditions and still feel some attachment to them, even if they don’t participate in the faith in any meaningful way. That’s a fairly straightforward hypothesis—and it’s easy to test by examining patterns of religious attendance

The Catholic percentages make perfect sense to me. Only about 15% of cultural Catholics report attending Mass weekly, and nearly 60% say they go to services less than once a year. That fits neatly with the idea of “secular” or cultural Catholicism. The contrast becomes even sharper when you look at religious Catholics: 29% attend Mass every week, and just 9% say they never attend religious services.

Then I turned to the Jewish results—and honestly, I thought I must have made a coding error. I expected cultural Jews to have very low attendance rates and religious Jews to be much more observant. Instead, I found the exact opposite. In this sample, cultural Jews were almost twice as likely as religious Jews to attend services weekly (28% versus 15%). There’s just no way that can be right… right?

I went back and checked—and then rechecked—my code to make sure I hadn’t reversed anything. I hadn’t. This really was the result. The explanation for this apparent oddity became much clearer once I looked at the current religious affiliation of people who said they were culturally Jewish.

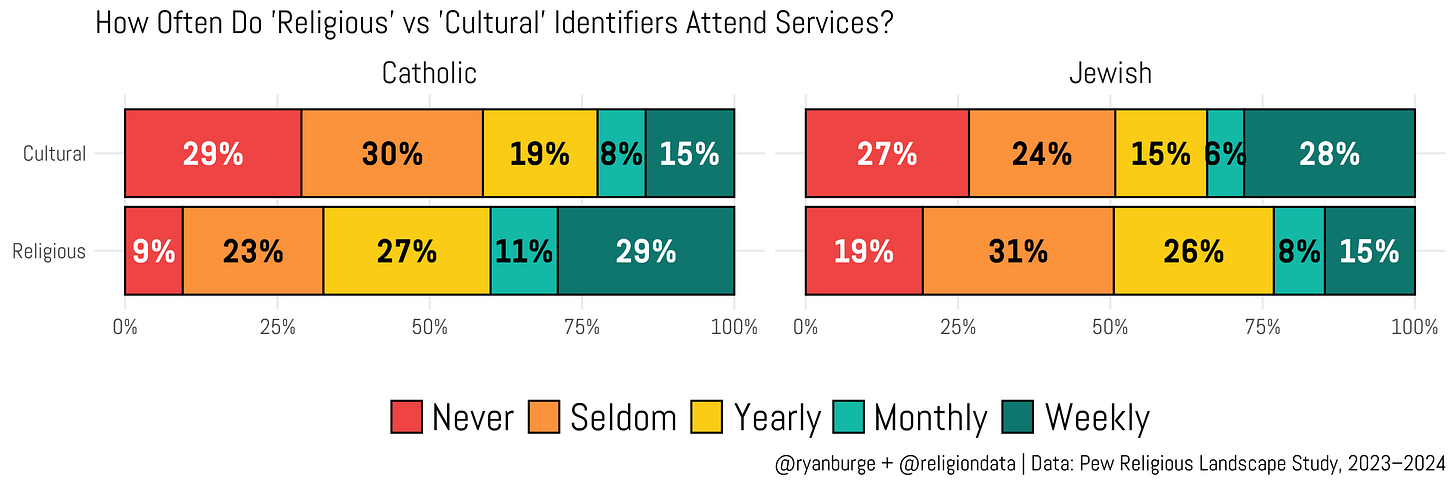

I would have assumed that a large share of both cultural Jews and cultural Catholics would currently identify as non-religious. That turns out to be mostly true for Catholics. A majority of cultural Catholics—53%—now identify as non-religious. Smaller shares come from different Protestant traditions: 18% are evangelicals and 14% are mainline Protestants. In other words, some cultural Catholics are actually Protestants who maintain an attachment to Catholicism through upbringing or, in some cases, marriage.

But take a look at the cultural Jews. I assumed that most of them would identify as atheist, agnostic, or otherwise non-religious. That’s not what the data show at all. In fact, only about one-third of cultural Jews report having no religious affiliation. Instead, the majority identify as Christians. Roughly one-third are evangelicals or mainline Protestants, and another 15% identify as Catholic. The takeaway here is unmistakable: a strong majority of cultural Jews are, in terms of religious affiliation, actually Christians.

This is exactly why I love working with data—it regularly upends my assumptions about how certain concepts function in American religious life. Cultural Judaism is not primarily made up of people who were raised Jewish and later became secular. Instead, it largely consists of Protestants and Catholics who feel some affinity for the Jewish roots or elements of Christianity.

That said, these numbers still need to be put in proper perspective.

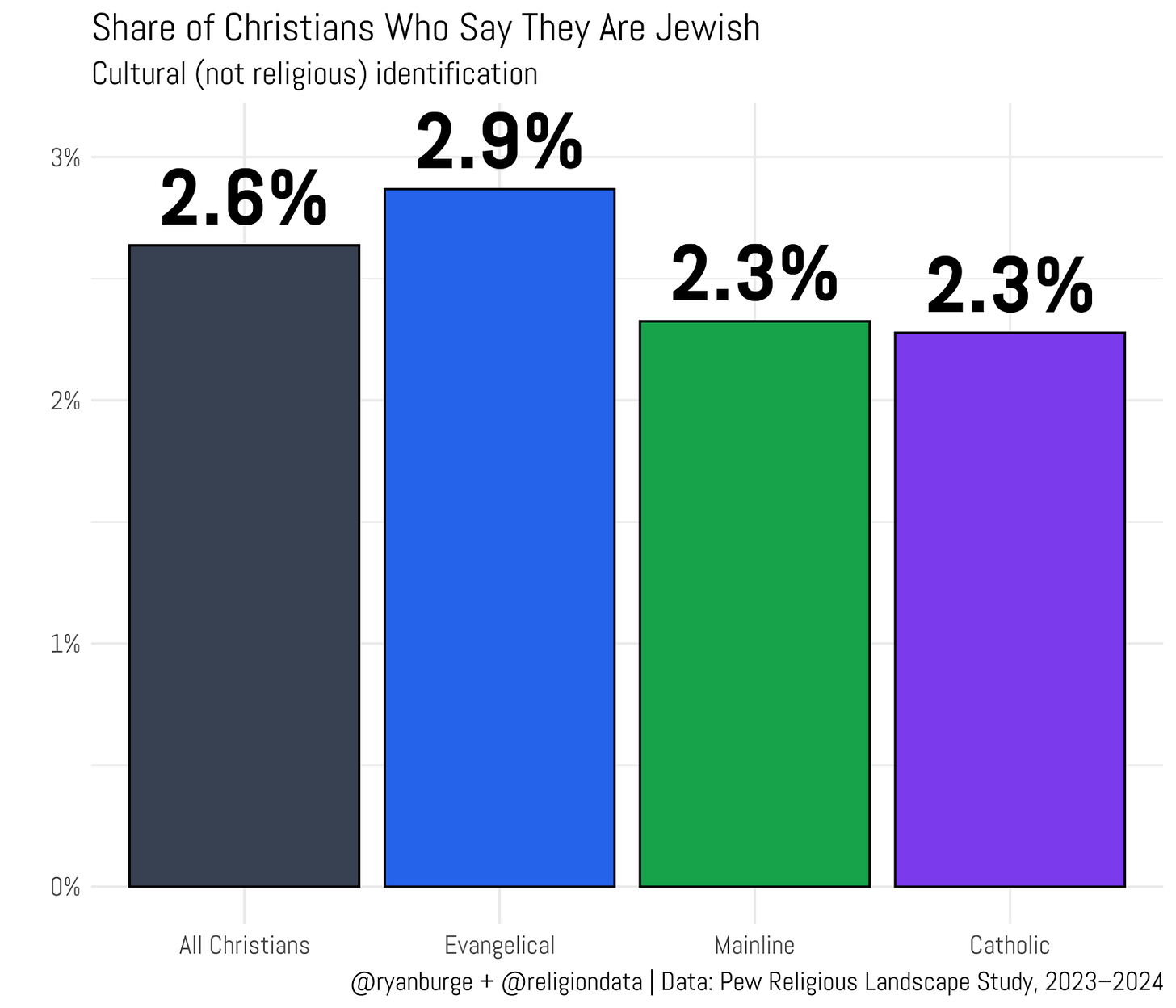

Among respondents who identify as any type of Christian (about 63% of all adults), the share who answered “yes” to the question about cultural Judaism is quite small—just 2.6%. In other words, roughly one in forty Christians say that they are also Jewish in some sense. This isn’t a widespread phenomenon within American Christianity; it’s a relatively rare identification. If we instead use the general public as the denominator, Christians who also identify as Jewish make up about 1.6% of all adults—almost exactly the same share of the population that identifies as religiously Jewish.

The data do show that evangelicals are slightly more likely than other Christian groups to say they are culturally Jewish (2.9% versus 2.3%). Still, I wouldn’t be comfortable arguing that evangelicals are meaningfully more likely to adopt this identity. In practical terms, the difference is quite small and not substantively significant.

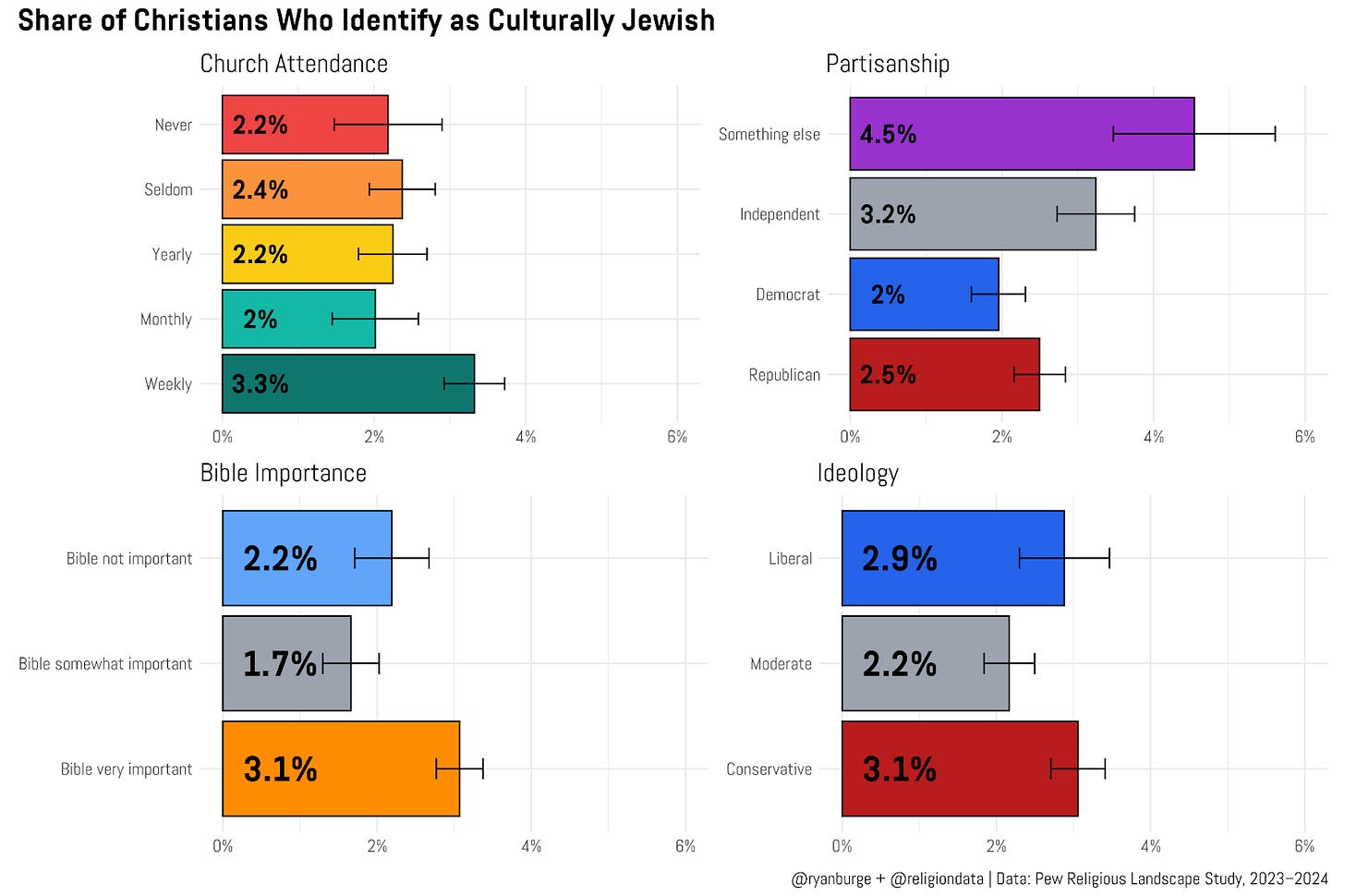

That led me to ask a different question: are there any characteristics that make a Christian more likely to identify as culturally Jewish? Perhaps it’s related to higher levels of religiosity—people who attend church frequently or place a strong emphasis on the Bible. Or maybe politics plays a role. Christian Zionism, after all, is closely tied to conservative theology and Republican politics. I tested each of those possibilities.

Christians who attend church weekly are slightly more likely to say they are culturally Jewish, but the difference is modest. Among Christians who attend less than weekly, about 2.2% identify as culturally Jewish. That rises to 3.3% among weekly attenders. The gap is statistically significant, but not substantively large. The same pattern shows up when looking at views of the Bible. Among Christians who say the Bible is very important, 3.1% report being culturally Jewish—about a percentage point higher than those who say the Bible is not important.

Ideology doesn’t yield anything meaningful. Roughly 3% of conservative Christians identify as culturally Jewish, which is essentially the same share as liberal Christians. Moderates are about a percentage point lower than both groups. Partisanship also offers little insight: Democrats and Republicans look nearly identical. The one exception is Christians who describe their partisanship as “something else,” among whom 4.5% say they are culturally Jewish. I don’t want to overinterpret that finding, though—it may simply reflect survey noise.

I love getting to write posts like this, and I’m grateful that ARDA (with support from the Lilly Endowment) makes this kind of analysis possible. What this exercise has convinced me of is that there are likely three broad ways that Judaism functions in the United States today.

Religious Jews. These are exactly who you’d expect: people who attend synagogue, read the Torah, and observe holidays like Passover and Yom Kippur.

Secular Jews. These individuals have an ethnic or cultural connection to Judaism but are religiously non-observant. Many identify as atheist or agnostic.

Cultural Jews. These are people who are religiously Christian but feel an affinity toward Judaism because of the deep historical and theological connections between the two traditions.

Of course, these categories aren’t rigid. Some secular Jews may still celebrate Hanukkah, and some cultural Jews may attend a Passover seder—even if they don’t believe the Messiah is still to come.

Religion is an amorphous and often confounding phenomenon. And it’s a genuine pleasure to get to trace its contours twice a week.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

The view from our sanctuaries and other gatherings might appear a little different than this. My orhodox Saturday mornings have mostly Jews. Not the case with the Conservative and Reform synagogues. They have Christian spouses in attendance and often participating in support of their partner. Many attend educational classes. All attend Seder. It's a trifle of the American population, but a significant presence in those congregations.

We Jews have another unique element. We are commanded to perform specified observances. We are not commanded to believe. There are many who would identify as agnostic on the first question, move to the second where they select Jewish. Many of those people engage in Jewish activities, including synagogue attendance, don't bring pork into their homes, donate to Jewish causes, and other things that make them part of the community mosaic. They may think of themselves as non-believers and respond to a survey that way. Jews who encounter them regard them as fellow Jews.

The third category is more problematic for us. There is a rising phenomenon of cultural approbation. That is Christians, typically evangelicals, who absorb Jewish behaviors as part of their practice. Some do not impact on Judaism. King Charles was circumcised as an infant by a mohel at his mother's direction. And neonatal circumcisions are common in post-natal units in America without introducing a Jewish identity. But there are also Christian Passover Seders, Christian homes with a mezuzah on the front door, and other practices that are particular to Judaism. This would come up on a survey of this format, very different people from the spouses of Jews and Jews of non-belief.

I wonder were Messianic Jews fit into all of this. I have had experiences with both Jews For Jesus and Chosen People Ministries, and the folks I worked with saw themselves as Jews who believed in Jesus -- in other words, kept Jewish religious observances, etc. Are they Christian Jews or Jewish Christians?