Women are more religious than men, right?

New Data Casts Doubt on the Conventional Wisdom about Gender and Religion

If you walked into my church last weekend, you would be struck by several things. The first is how few people are in the pews each Sunday. We are lucky to get to double digits many weeks. The second is how few men there are among the faithful. An average Sunday may have eight women and four men. There have been weeks where there are two men.

I say this without a sense of exaggeration: if our church didn’t have women take over leadership roles, we wouldn’t exist right now. They are backbone of our congregation.

The conventional wisdom is that women are just more religious than men. A Pew study looked at religiosity around the world and found exactly that, “Women are generally more religious than men, particularly among Christians.”

Pew has a very nice summary of some of the possible reasons for the gender gap in Chapter 7 of their report. They point to a mixture of explanations that are both genetic and environmental which drive women to seek out religious community. It’s likely a highly complicated mix of a variety of factors that don’t work the same for every person.

But recent data from the Cooperative Election Study may be casting some serious doubts on that long held assumption about religion and gender in the United States. Let’s start with the graph that launched this entire investigation.

This is the share of women and men who identify as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular based on birth year. I am showing you every election year in the CES because the sample size is particularly large during those collection periods.1

Notice anything? Among older folks, the lines typically run in parallel to each other. Men are slightly more likely to be non-religious compared to women. It’s not a huge gap, for instance a man born in 1970 is about 5% more likely to be a none than a woman of the same age.

But then when we start examining the youngest adults (those born in 1990 or later), the lines begin to intersect. That’s especially clear along the bottom row. Among those born around 2000, the gap has essentially disappeared - women are just as likely to be nones as men. This same general trend is evident in the last three election years of data. It’s hard to believe that it’s just noise when it’s so replicable.

I wanted to take a deeper dive, so I took a look at a different dataset: the General Social Survey. I restricted the sample to just 18–25-year-olds and there is clearly something going on here, too.

Those parallel tracks are clearly there in the data from 1988 through 2015 or so. Men are about five percent more likely to be nones than women. But then the line for women begins to shoot up, while the line for men only rises slightly. In the 2021 data, over half of young women are nones compared to just 40% of men. This may be just some oddity with the recent GSS data that I discuss in depth in this post:

But it’s pointing to the same conclusion as the CES: women are less religious than men.

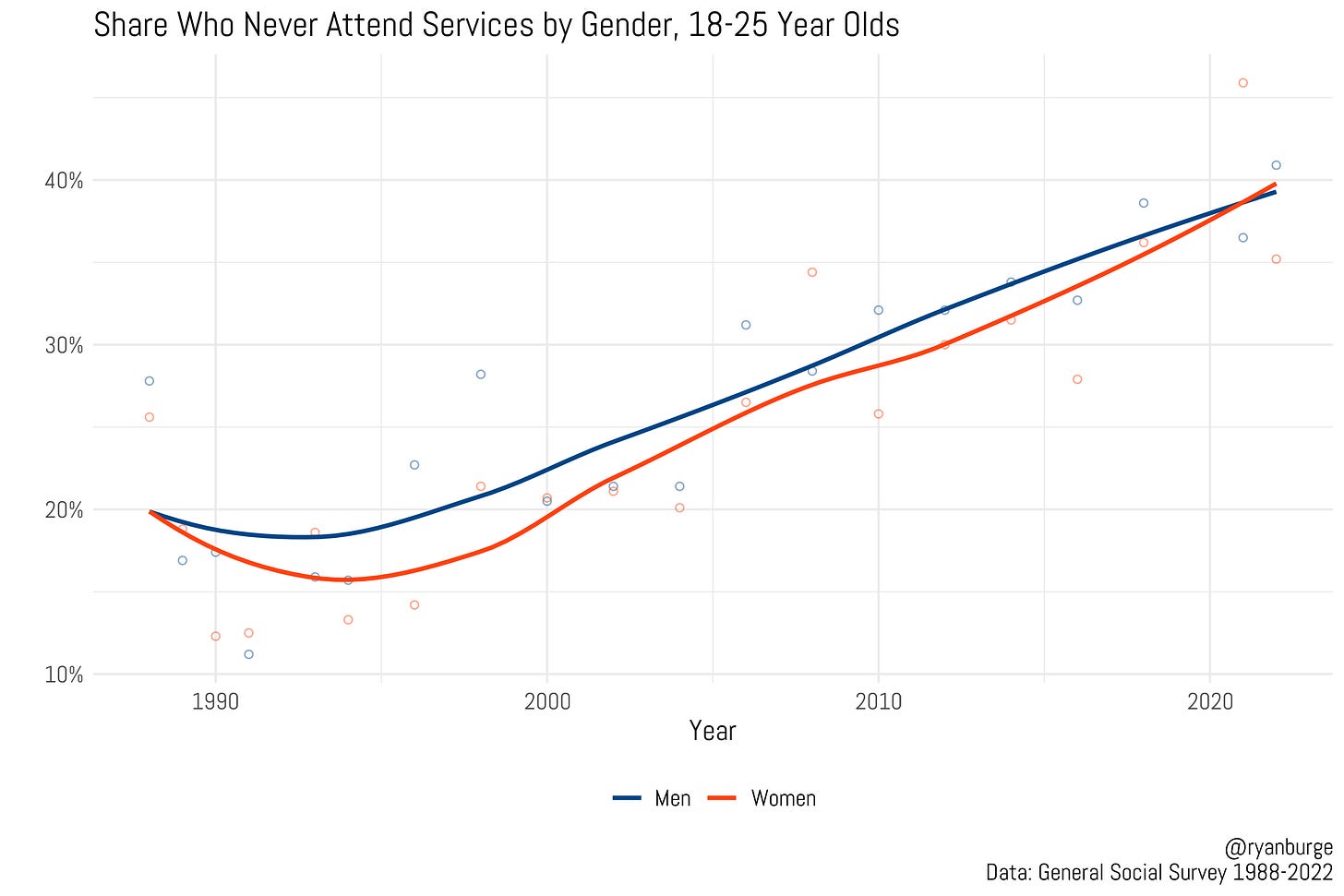

What about church attendance? Here the results are not so dramatic, but still point in the same general direction.

The share of men who never attend church ran a few points above women for the last several decades, then in the recent data, the lines begin to intersect. Now, about 40% of young men and young women indicate that they never attend religious services.

Taken together, there is some pretty good evidence coalescing that the gender gap when it comes to religion has disappeared. Young women are just as likely to never attend religious services as young men, and it’s possible that young women are even more likely to say that they have no religious affiliation.

But, why? What’s driving the disappearance of the gender gap? Is this about politics, or education, or race, or something else that’s hard to explain? Here’s my attempt at trying to figure out this puzzle.