The God Gap in American Politics

If there’s one catch phrase in my little corner of the social science world it’s, “The God Gap.” It’s the simple idea that the Republicans have become the party of religious folks, while the Democrats are much less religiously inclined.

If you read a bunch of papers that use that term and try to trace it back to its origins you get a lot of different answers. It certainly plays a significant role in Geoffrey Layman’s first book The Great Divide which was published in 2001. He had already noticed that there was a great divergence in the religiosity of Democrats and Republicans. He wrote on page 11:

[C]onservative Protestants abandoned their apolitical moorings in the late 1970s and early 1980s. With encouragement and assistance from organizations such as the Moral Majority, the Religious Roundtable, the Christian Voice, and later the Christian Coalition and the Family Research Council, religious conservatives became actively involved in battles over cultural issues such as abortion, the place of religion in the public schools, pornography, gender equality, and homosexual rights, and they infiltrated the ranks of the Republican party to fight these battles.

However, it also plays a prominent role in Putnam and Campbell’s seminal book American Grace which was published in 2010, especially in Chapter 4 in which they describe recent American religious history. Their narrative is that the counter-culture movement of the 1960s and 1970s led to a backlash among people of faith. In other words, the rise of the Religious Right was a direct result of the hippies of a decade or two earlier. They write, “[V]irtually every major theme in the Sixties’ controversies would divide Americans for the rest of the century, setting the fuse for the so-called culture wars.”1

How this happened, exactly, is still a matter of fierce debate among political scientists, sociologists, and historians - but the upshot of all this is the same - the modern Republican party is a whole lot more religious than the modern Democratic party. That’s all I wanted to do today, is make that evidence clear. Not really come up with my own explanation for why this is this the case.

As I have written elsewhere, religion is conceived to run on three dimensions:

Belief - this is measured in a variety of ways including view of the Bible, belief in angels, demons, God, heaven, hell, etc.

Behavior - this is almost always measured by religious attendance

Belonging - this is what group you identify with on a survey - Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, No Religion, etc.

So let me visualize how the two major parties have diverged on these metrics over the last couple of decades. Let’s start with belief in God, a question that has been included in the General Social Survey with regularity since the early 1990s.

As can be seen from the top row of bars, there was very little difference in the religious beliefs of the average Democrat and the average Republican in the 1990s. About two-thirds of Republicans had a certain belief and it was just a few points lower for the Democrats. Also, the share who didn’t believe in God was small for both groups. It’s not like there were a bunch of atheists on either side of the aisle in the 1990s. About 80% of Democrats and 85% of Republicans chose the two most certain responses on religious belief.

That gap does begin to widen the next couple of decades, though. While the gap in certain belief was just four points in the 1990s, it was eight points in both the 2000s and the 2010s. In fact, by the 2010s, the share of Democrats with a certain belief in God had dropped eleven points. For Republicans the decline was only three percentage points. The share who took an atheist or agnostic view of God was still fairly low for Democrats, though. Even into the 2010s, just one in ten Democrat gave one of these two response options.

The 2020s data only reflects two total surveys, but it’s clear from that the God Gap is huge when it comes to religious belief now. The share of Democrats with a certain belief in God dropped thirteen points in just one decade, while the Republican share hasn’t budged. In total, certain belief for Republicans has dropped by four points. It’s twenty-four points for Democrats.

How about religious behavior, though? I analyzed the GSS question about religious attendance and this time I can stretch it all the way back to surveys collected in the early 1970s.

It’s pretty striking to see how little variation there was on religious attendance when comparing Democrats to Republicans in the 1970s and 1980s. Yes, Republicans were more likely to be weekly attenders, but the gap was just four percentage points in those two decades. And there was not a real gap on the share of never attenders, either. It was 13% of Democrats and 11% of Republicans, certainly not anything to write home about.

The God Gap begins to emerge in the data collected from the 1990s - now a Republican was seven percentage points more likely to attend weekly than a Democrat. However, it’s not like the Democrats had abandoned churchgoing. About half of them darkened the church door at least once a month and only 16% said that they were never attenders.

By the 2000s, the gap had become much more apparent. The share of weekly attending Republicans was 40% compared to only 28% of Democrats and a Democrat was about 50% more likely to be a never attender compared to a Republican (21% vs 14%). The attendance of Republicans and Democrats continued to diverge in the 2010s, too. Never attending jumped by seven points among Democrats and only four points among Republicans. It’s also worth pointing out that among Republicans, the share who were weekly attenders dropped by just two points between the 1970s and the 2010s. It was eleven points among Democrats.

Data from the last couple of years does show a significant erosion in Republican church going, though. Never attending Republicans increased by four percentage points, while weekly attendance reported a six point decline. In the 2020s, the share of Democrats who never attend rose to 35% (up seven points from the prior decade), while weekly attendance dropped a corresponding six points.

What about religious affiliation? I collapsed all the categories into just four: Protestant, Catholic, No Religion, and everyone else.

Almost everyone was a Christian in the 1970s, very few folks were nones. I may have written a book or two about that. But the Democratic party was a lot more Catholic compared to the Republicans (31% vs 18%). That’s really the only thing to glean from this early data. There was no God Gap when it came to religious belonging. That’s also the case when looking at the 1980s, too. Although, the Catholic share was starting to creep up among the GOP - rising from 18% to 23%. This may have something to do with the ascendance of the Religious Right. But that’s a topic for another day.

The rise of the nones begins to emerge in the data from the 1990s. About 11% of Democrats claimed no religious affiliation during this decade, while it was half that rate among Republicans (6%). For Democrats, those 'none' pickups came exclusively as a result of losses in the Protestant share - it dropped by six points between the 1980s and 1990s.

What follows is an increase in the nones among both Republicans and the Democrats, but the nones are clearly flocking to the Democrats in much larger numbers. It went from 11% in the 1990s to 16% in the 2000s to 24% in the 2010s to 34% in the 2020s. Basically a tripling in the nones during this time period. For Republicans, there are gains too: 6% to 9% to 11% to 15%. But think of it this way: the difference in the nones between the two parties was five points in the 1990s. Today, it’s nineteen points.

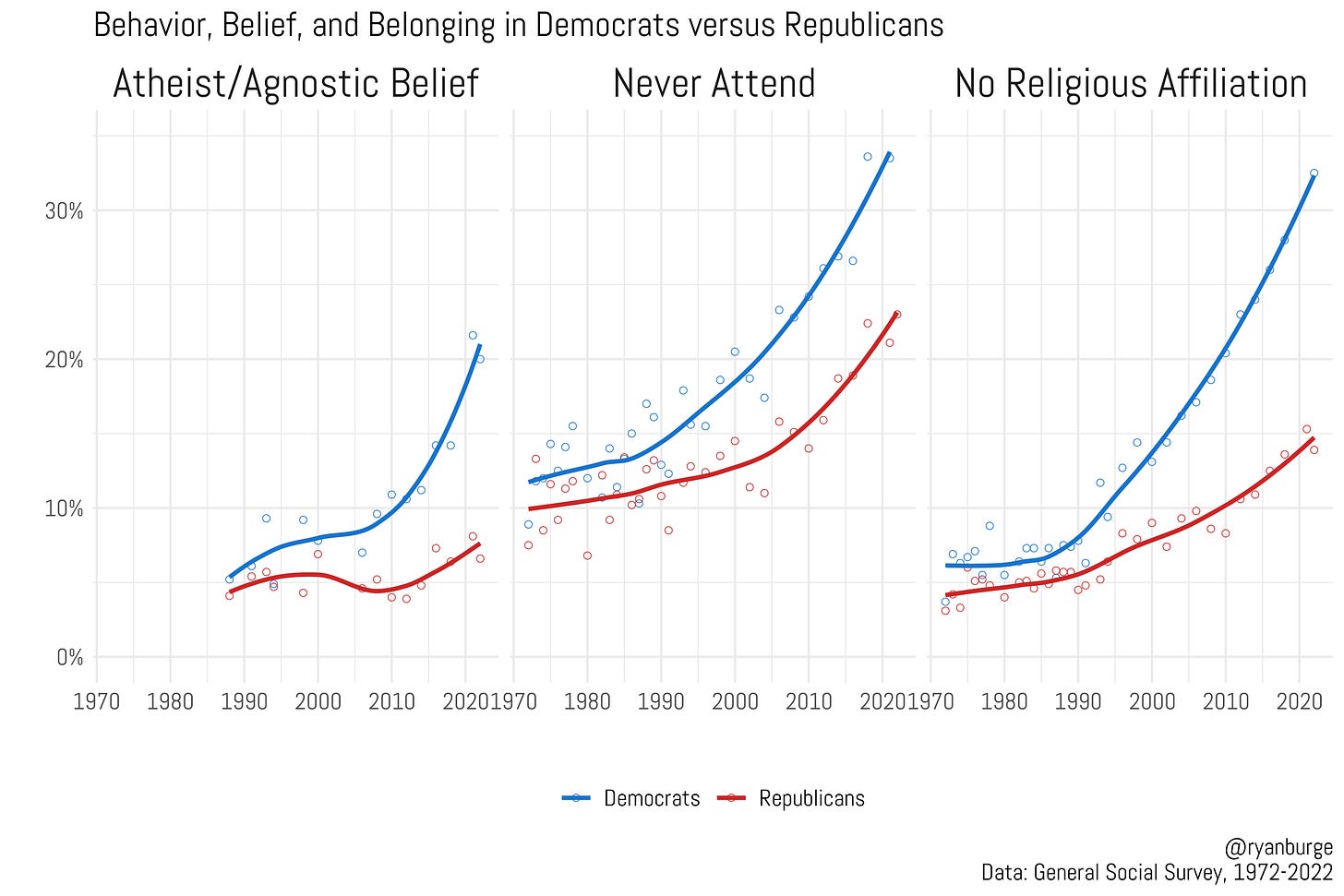

Let me throw this all together now into a single graph to really simplify this and help us see more clearly when the gaps begin to emerge.

When it comes to belief, the trend lines are clear on this point - it’s really in 2010 and beyond when the gaps between Democrats and Republicans explode. The gap between the share of each party that held to an atheist/agnostic belief was pretty small - never more than five points. But within a decade it had nearly tripled. Now, about 21% of Democrats don’t believe in God, compared to 8% of Republicans.

For attendance, there’s not really a clear inflection point. It does look the lines begin to diverge more sharply after 1990 but it’s not a clear break. From this angle it appears that the share of Democrats who never attended religious services rose more quickly in the 1990s than it did for the Republicans. In my mind, the smallest God Gap can be found on religious behavior, though.

When it comes to belonging, 1990 is really the hinge. There was almost no gap between the two parties prior to this point in time. But from that point forward, the nones rise incredibly rapidly among the Democrats. It’s a much more modest increase among the Republicans.

This is a topic that I am thinking about a lot lately. I am in the process of writing a book for Brazos, that will hit the shelves in early 2026 that tries to detail the very real phenomenon of religious polarization and the implications that it will have on American democracy and let’s just say - I’m a bit worried. Politically diverse religious spaces were the norm in the United States for most of our history - that’s changed rapidly and dramatically in the last couple of years. The book is heavy on description but also a bit prescriptive. I am pleased with the way that the volume is shaping up and I am excited for you all to read it.

Code for this post can be found here.

I am very excited for the upcoming book. It is imperative that we can forecast how our culture will look like in the near and far future. Great article.

A set of charts that would have been interesting to include would have been an inverse of the membership charts. Since you clumped all religious identification into four categories, instead of two bars per decade, you could have had four and shown what percentage of Protestants, Catholics, Nones, and other identified as D or R. It would be interesting to see what kind of shift there might have been by believers in their partisan leaning alongside the shift in religious identification among the parties.