The Generational Collapse of American Religion

An Age–Period–Cohort Story Told Through the GSS

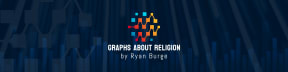

Buckle up, readers, because we’re about to do a deep dive into an important but difficult-to-grasp concept in the social sciences. It’s called age-period-cohort (APC) effects. Let me start by showing you a simple graph. All I’m doing here is comparing attendance in the first year of the General Social Survey (1972) to its most recently released data from 2024.

You can see that I’ve broken the sample down into five age buckets, ranging from 18–29 years old to those who are at least 75. What do you notice? Well, the first thing that jumps out to me is that religious attendance has dropped significantly in the 2024 data compared to the same age buckets in the survey from the early 1970s.

For instance, among 18–29 year olds in that early survey, just 19% said they attended religious services less than once a year. For that same group in the 2024 data, almost half were in the never/seldom category. An increase of thirty percentage points. That’s a universal finding, by the way—no matter what age category you compare, the 2024 sample is significantly less religiously active.

But, of course, that’s not the only way to look at this graph. You could simply compare the age buckets in the 1972 data against each other and do the same with the results from 2024. What you find there is that younger folks are much less religiously engaged than older ones. In 1972, a 75-year-old was about 20 points more likely to be a weekly attender than an 18–29-year-old. In the 2024 result, the gap was 23 percentage points.

The last paragraph (where I compared older respondents to younger ones) is a good example of an age comparison. The previous paragraphs, which compared young adults in 1972 to young adults in 2024, are examples of a period effect. I’m holding age constant while looking at how religious engagement has changed across historical time.

But there’s one more part to any APC analysis—cohorts. A birth cohort is sometimes called a “generation” in common parlance. For instance, Millennials are technically a birth cohort, and so are Baby Boomers. But the better way to operationalize cohorts is five-year birth windows. It’s more reasonable to assume that someone born a couple years before or after you experienced the same life events at essentially the same stage of development than to do it by generations that often span 15+ years. I’m actually going to use both strategies in the rest of this post.

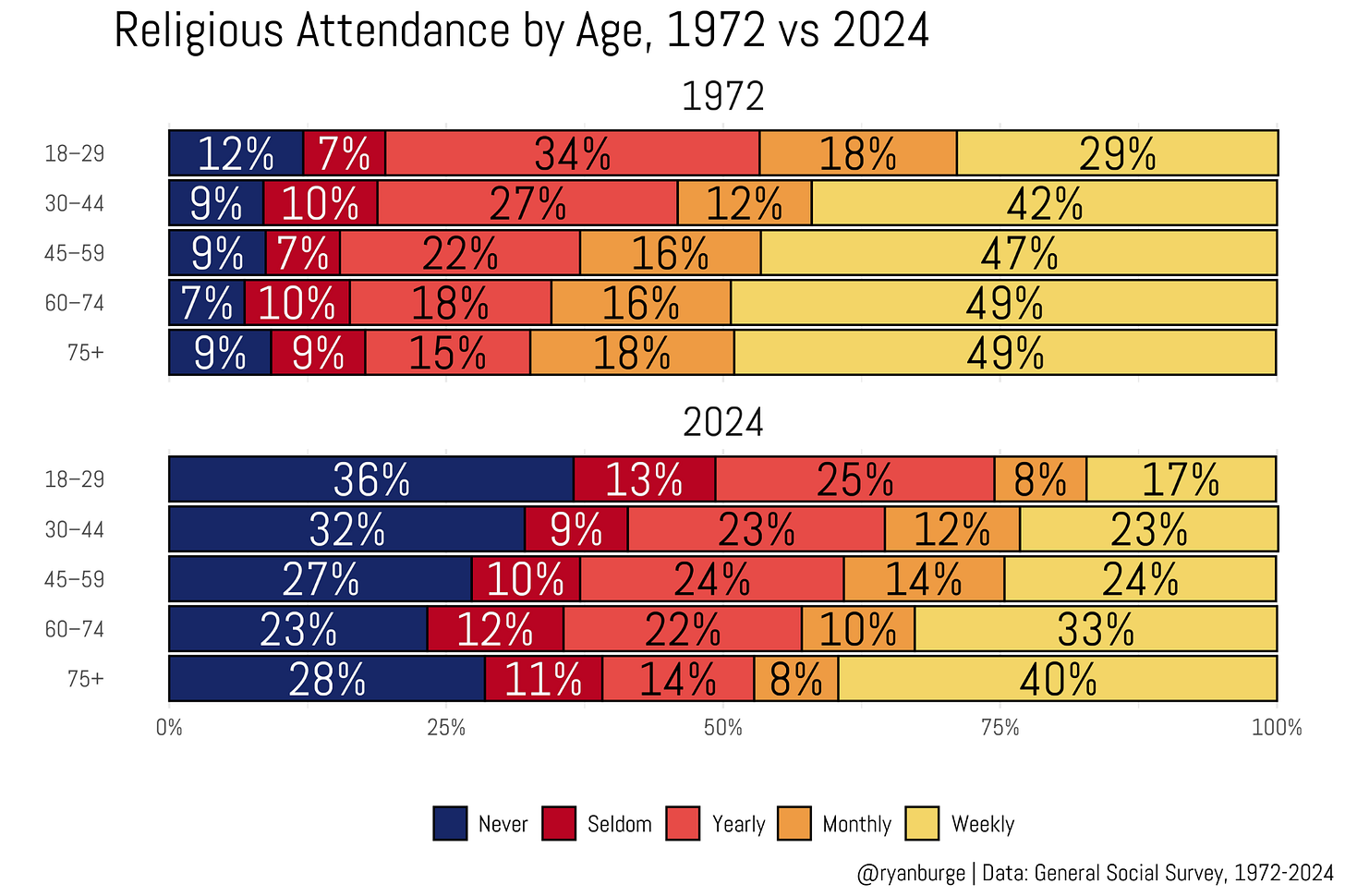

There’s a commonly held conception of how birth cohorts age when it comes to religion—it’s called the “life cycle effect.” I’ve done my best to visualize the most widely held understanding of this process in the graph below.

When kids are growing up, they are pretty religious. That was certainly true of Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation. But it’s also the case that a huge majority of Millennials and Gen Z were raised in fairly religious households. Parents want their kids to have some sense of morality, so they send them to church and youth group and all that.

But then those kids become young adults, and they head out into the world and determine what parts of their childhood they want to keep and which ones they want to leave behind. So religiosity tends to dip in young adulthood. Life is chaotic then—college schedules, relationships, moving constantly. It’s hard to find a routine.

However, the next phase is when folks begin to settle down. They get married and have kids. Their work situation often stabilizes, and they want to repeat many of the touchstones of their youth, including sending their kids to Sunday School and church camp. And they don’t want to seem like hypocrites, so the parents attend church with their kids.

You can probably guess what happens next—those children graduate high school and leave the nest. Which means their parents have a choice: walk away from church or devote more time and energy to their faith community.

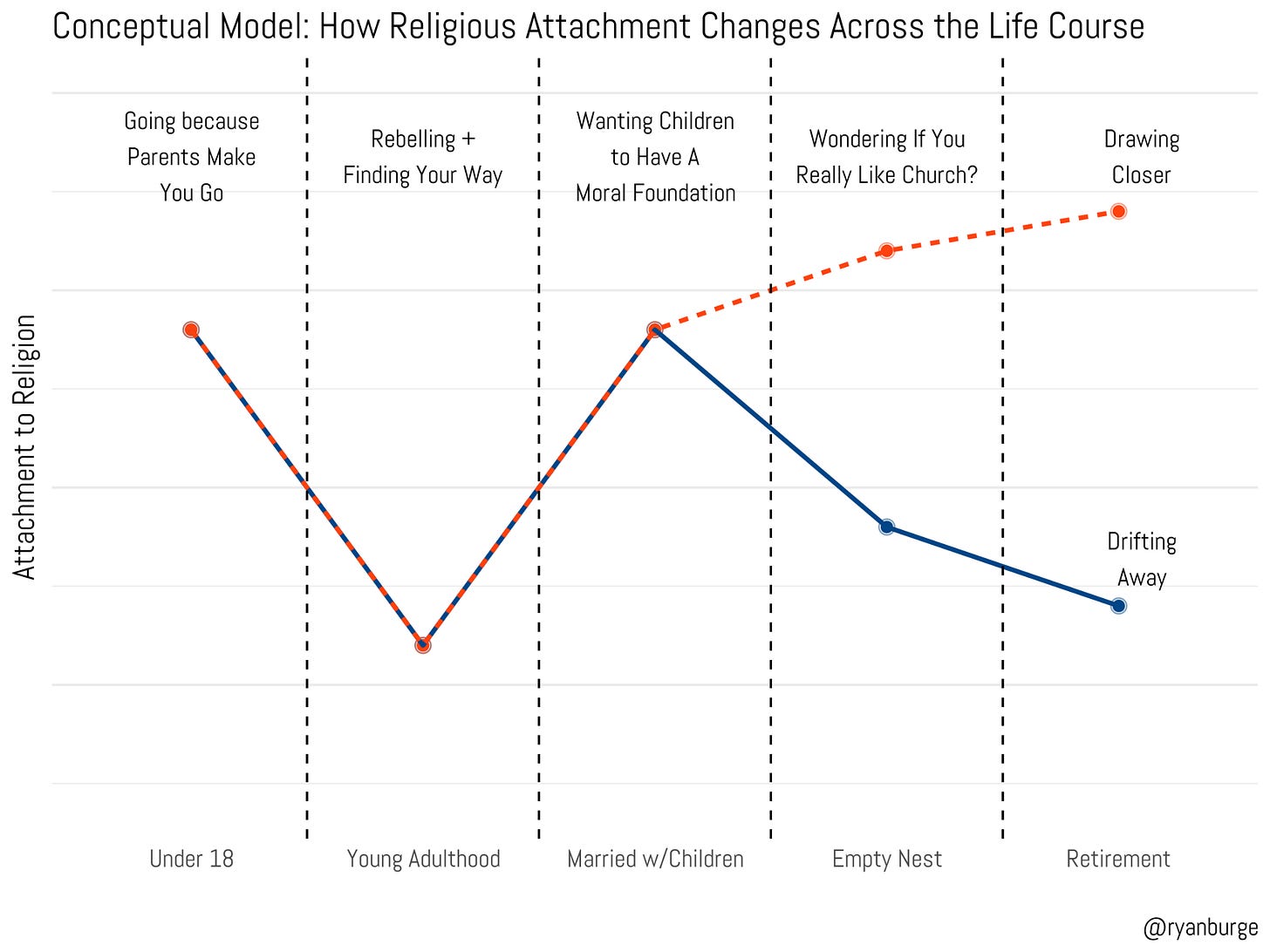

But is this model actually accurate? Well, because the GSS has been ongoing for over five decades now, we can actually trace several generations through basically all the steps of the life course. That’s what we see below.

I really want to highlight the Silent Generation, because when the GSS started in 1972, it was picking up the tail end of that generation who were still in their twenties. According to the GSS, 33% were weekly attenders. But as they aged into older life stages, their attendance actually rose. And the rise was really remarkable: it climbed to 39% when they were in their late forties and fifties. And in the last life stage (75+), nearly half of Silents (47%) were attending nearly every week or more. That’s a 14-point rise as they aged through.

But compare that to Baby Boomers. There’s only one significant shift for them as they aged. When they were 18–29, 25% attended weekly. Then attendance rose to 31% between ages 30–44 and has basically stuck there for a very long time. And guess what we see among Gen X? Basically the same pattern—a rise from Stage 1 to Stage 2 and then a plateau. This time, it’s around a 25% weekly attendance rate.

Then look at Millennials. We only have two data points. When they were 18–29, 19% were weekly attenders, and now it’s 20%. That’s essentially stability.

I want to make two points clear.

There is decent evidence of that bump in attendance when Boomers and Gen X aged out of young adulthood. Attendance increased by six and four points, respectively.

There’s no real evidence that people become more religiously active as they age beyond that initial surge. For every generation born after 1945, attendance has remained remarkably stable for decades. Among the last three generations, there’s simply no sign of a late-life return to church.

But remember how I talked about generations being a pretty imprecise way to do this type of analysis? They are, of course, because there are Baby Boomers born in 1946 who had children who were also Baby Boomers (born in 1964). That makes no sense at all.

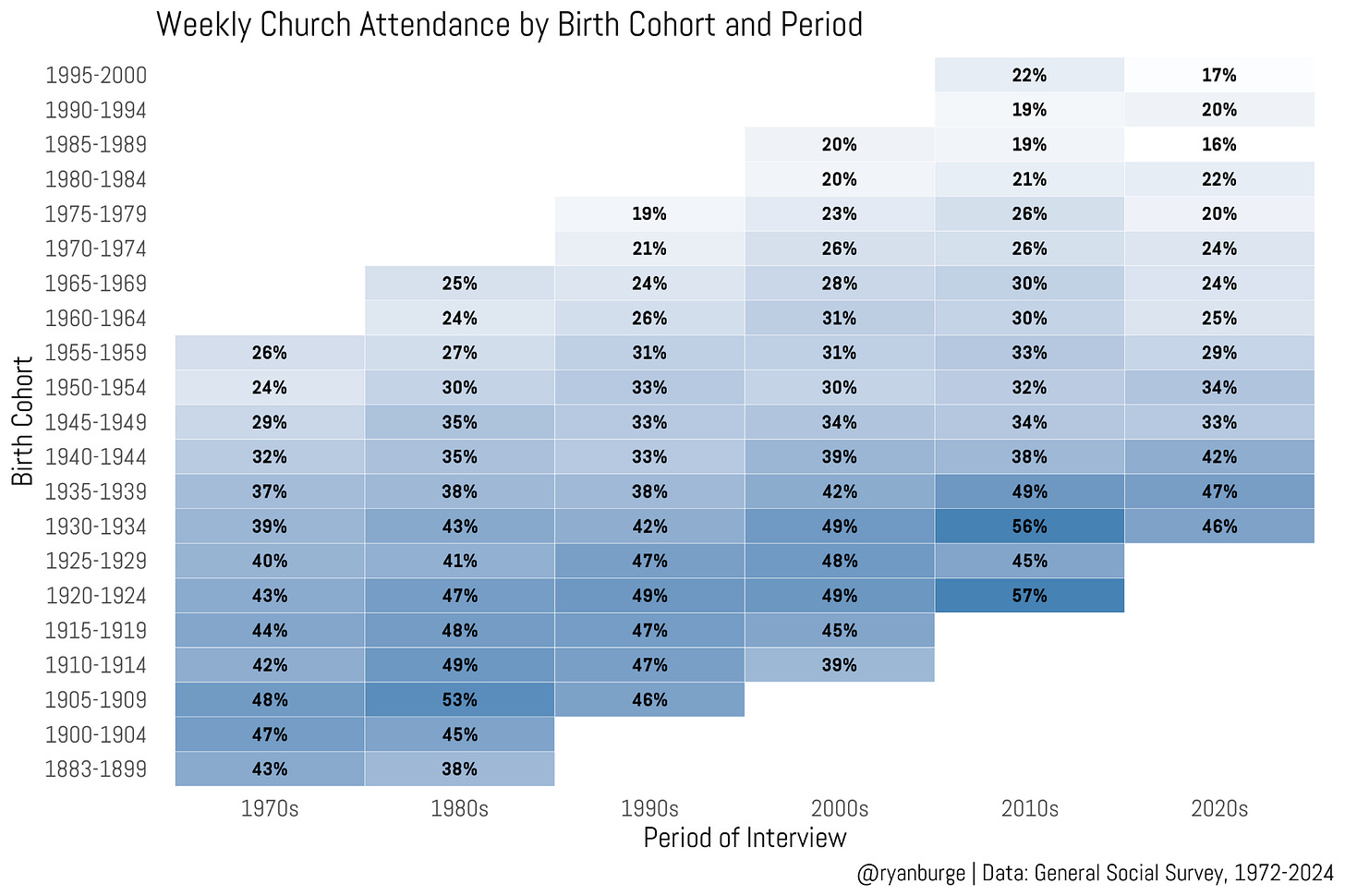

So let’s get more granular by breaking this down into five-year birth cohorts and calculating attendance in each decade of the GSS for all those cohorts. I removed any cell that had fewer than 50 respondents. And I have to say, I really do love this graph. Let me describe why.

If you scan your eye vertically up each column of numbers, what you essentially see is how religious attendance varies by age at a given point in time. You have older folks at the bottom of the heatmap and younger respondents at the top. For instance, look at the 1980s column. Among people born in the 1910s, nearly half of them reported weekly religious attendance. These folks were in their seventies when they took the GSS. But when you look further up, you can see people born in the 1960s—they were in their twenties when they answered the survey. Among this group, just a quarter were weekly attenders.

But then if you scan your eye horizontally, you can track how each birth cohort has changed their religious behavior as they aged through the life cycle. We have a really complete set of data for folks born in the 1930s. When they were first surveyed in the 1970s, 38% reported attending nearly every week. People born during that same window were polled by the GSS in just the last few years, and nearly half of them said that they were attending weekly. We saw this same basic idea in the line graph above: Silents became more religiously active as they aged.

But for birth cohorts near the top of the graph, you can see almost no change when scanning from left to right. Those cohorts do not change their overall level of religiosity as they age. In many cases, comparing the results from the 1990s to the 2020s shows a net change of only a point or two in either direction.

So why do overall levels of attendance decline? Well, because each successive birth cohort is less religiously active than the previous one. That’s the main driver of religious decline—it’s a decay function across cohorts.

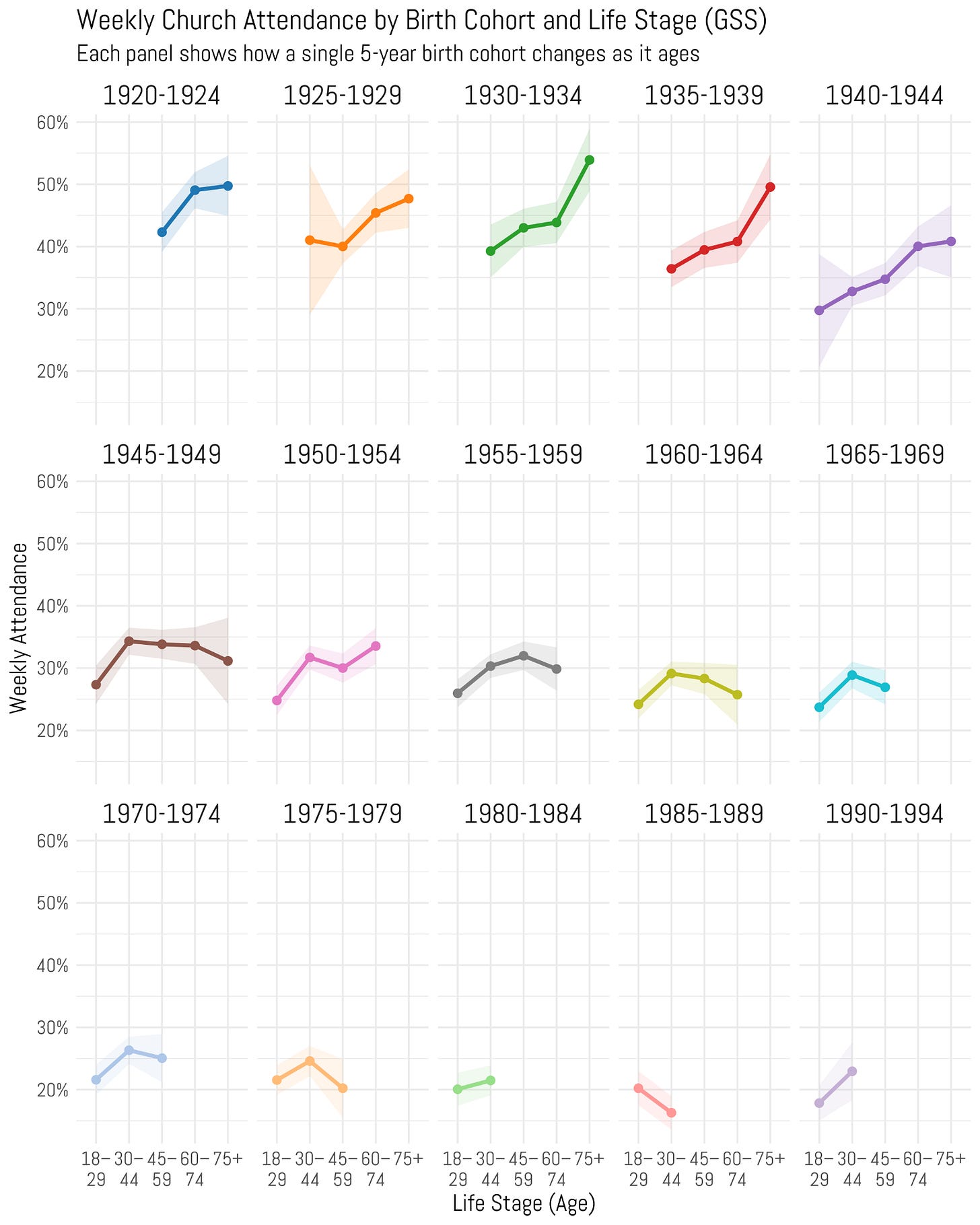

Let me show you this one more way before I close up. These are five-year birth cohorts, and I tracked them at five different life stages throughout the last fifty years of the GSS.

This puts a nice bow on what I described before in the previous graphs. Notice the top row—that’s folks who make up the Silent Generation. Their attendance clearly continued to rise as they aged. It’s as clear as day for people born between 1925 and 1945. And these jumps are massive. For those born in the 1930s, about 40% were weekly attenders in their 30s. By the time they hit their 70s, attendance rates were 55%.

But then take a look at the second row of results. Those are much “muddier” than the first set. We do see a consistent pattern—a bump in attendance at 30–44 years old. That’s there even through cohorts from the 1970s as well. Attendance is at a trough in the 18–29 period. But notice what happens after that life stage? A whole lot of stability. In the top row, the line kept going up. In the middle row, it basically stays the same.

What can we say about the bottom row? Well, we are constrained by fewer data points. But I think it’s fair to conclude that the increase in attendance at 30–44 is not materializing for Millennials. And for those born in the late 1980s, there’s some evidence that attendance kept falling at the 30–44 checkpoint. That has never happened before.

So, there’s a lot to digest here. Let me break down some big takeaways.

Religiosity is declining (in large part) because each successive generation is less religious than the one before it. But their overall religiosity doesn’t really decline as they age. It stays stable—just at a lower level.

The idea that “settling down” leads to a jump in religiosity is supported among older generations, but it may not hold going forward. We just don’t have enough evidence right now to say that younger cohorts will follow that same pattern.

Of course, there’s a huge question mark hanging over all this: why is religion not being handed down more effectively in the United States? That’s a much harder one to answer with just a couple of questions from the General Social Survey.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

Hooray for using birth cohorts! Really, a much more explanatory measure than Generations and uses a fact-based descriptor instead of what can be an "othering" label.

The graph and table with shaded boxes is a great way to illustrate age-period-cohort analysis.