The Four Types of Nones

A new understanding of 30% of Americans who are non-religious

As some of you know, Tony Jones and I won a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. It was part of the foundation’s Spiritual Yearning Research Initiative. Our specific project is titled Making Meaning in a Post-Religious America, the centerpiece of which is a huge survey of the non-religious with questions specifically tailored to explore the nuances of the nones in a way that we haven’t been able to do with previous survey methods.

About a year ago, we put that survey instrument into the field using Qualtrics, which is widely used in both the business and academic worlds to provide high quality data. The total sample size for this data collection effort was 15,296 Americans: we gathered responses from 12,014 folks who identified as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular (the nones).

We also polled 3,282 people who said that they were a member of any religious group. It was primarily Protestants and Catholics, but there were also some Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, etc. as well. The reason for including that part of the data collection effort was simple: we need a group to compare the nones to on all these metrics. They are our ‘reference case.’ (Just so we have full transparency on this, this effort cost about $110,000. Doing good data work is not cheap!)

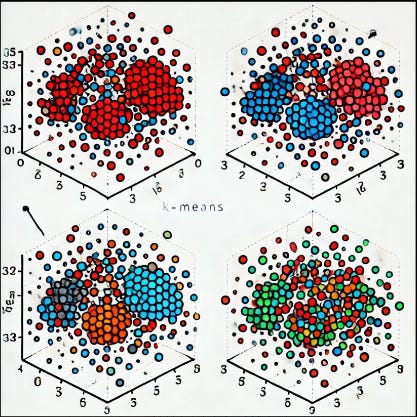

To create our new typology of the nones, we used a bit of machine learning. In this case, it was k-means clustering. It’s a pretty simple process, really. You pick some variables that you think that might be meaningful in creating categories and then let the algorithm find commonalities in the dataset. We chose this process because it achieves an important goal in this type of work: it’s atheoretical and (theoretically) unbiased. The computer has absolutely no idea what any of the numbers mean — it just sees a bunch of values that range from zero to one.

We didn’t want to bias the process with our own assumptions of how the nones should look. In the end, it didn’t take that many survey questions to create our categories and we will actually publish a full writeup of the variables we included and the code to recreate this analysis on other survey datasets in the future.

We landed on four categories of the non-religious for both statistical and practical reasons. The data really did say that four types of nones is the optimal number (using the elbow method). But we also know that it’s hard for people to remember a dozen different groups. You’ve got to find the sweet spot between simplification and over-simplification. We think we’ve found that by creating the four types of nones.

So, without further delay. Here is our understanding of what the non-religious looks like in the United States.

The four groups are: NiNos (Nones in Name Only), SBNRs (Spiritual but not Religious), the Dones, and the Zealous Atheists. Some of these groups are pretty well known to interested observers of the study of non-religion in the United States. For instance, SBNRs has been a concept that has bounced around the literature for decades in journal articles and books. I’ve written about it in my newsletter as well. And the term “Done” is already out there, too. Daryl van Tongeren (one of our consultants on this project) wrote a book with that same title just a few years ago (though we use it a bit differently from Daryl, as you will see below).

But we’ve also got two categories here that are brand new to the study of the nones: NiNos and Zealous Atheists. We think both those groups add a ton of nuance and understanding to what secularism looks like in this part of the world. It’s important to note that the classification typology does not draw bright lines around people. Most nones don’t fit completely into one of these buckets, but we believe most are primarily rooted in one of the four types.

Let me briefly describe each type now.

Nones in name only make up 21% of the entire non-religious sample. You can probably guess how this group got their name — they are actually fairly religious on a bunch of metrics, but they still don’t classify themselves as part of a religious group. When it comes to the traditional religion question, almost three quarters of them describe their religious affiliation as “nothing in particular.” This group scores the highest on both religious importance and spiritual importance.

There are some fascinating results here: one third attend a house of worship at least once a year, over half of them say that they pray on a daily basis and a similar percentage say they believe in God without a doubt. You see what we mean when we say that they are ‘nones in name only’?

Now, it is important to note that they are not nearly as religiously engaged as Catholics or Protestants. Their attendance is still far lower than other religious groups, but when compared to the other three types of nones, they are much more religiously attached. We actually believe that this group poses a methodological problem for researchers. For reasons that we will explore in a future post, these people aren’t able to classify themselves properly based on the current approach to asking about religious affiliation.

Spiritual but not Religious (SBNRs) are likely the most recognizable group to people who aren’t very familiar with the literature surrounding secularism in the United States. In our sample, this was the largest group of nones at 36%. These people are exactly what you would think they would be: deeply skeptical of religion but highly interested in spirituality. In fact, of all four groups they had the biggest gap between religious importance and spiritual importance. Which makes sense given their anti-institutional stance.

On the traditional measures of religiosity, this group scores incredibly low. For instance, 93% of them describe their church attendance as seldom or never. When asked about prayer, nearly 9 in 10 SBNRs say that they hardly ever pray. And it’s hard to find an SBNR who has a strong belief in God. Just 5% said that they believe in God without a doubt. They are much more likely to fit in the “I believe in some Higher Power” category.

It should come as no surprise that about three-quarters of the SBNRs say that they trust in religion “not at all.” These are the new age spiritualists who explore spirituality through practices like crystals, yoga, meditation, walks in nature, etc. We are going to explore this dimension of SBNRs in a whole lot more depth in some future posts.

Of all four groups that we uncovered, the Dones were the easiest to label after taking a quick glance at the data. These people are, quite literally, done with religion entirely. In total, they make up one-third of all non-religious respondents. On both measures of religious importance and spiritual importance, you can’t get much lower than the Dones. One of the questions that Spiritual Yearning Initiative was trying to answer was: Does everyone yearn for God? In the case of the Dones, we feel confident in saying that there is no clearly articulated “God-shaped hole” in the hearts of these folks.

You should not be at all surprised to learn that they engage in no traditional religious practices. Just 2% of them attend a house of worship at all, and 99% of the Dones just don’t pray at all. And, among the Dones, it’s basically impossible to find one that has a certain belief in God. When we say that they are done with religion, that’s the unmistakable conclusion from this data.

What really crystalized this fact was a set of questions we asked each person about the afterlife. One statement was, “When I die, my existence ends.” Among the NiNos, 26% agreed. It was 39% of the SBNRs. For the Dones? 77% of them said that this is all there is to life. For them, death is it. They become worm dirt. We are going to explore the depth of this in some future posts.

This last group was the biggest surprise to Tony and me and we went back and forth trying to name this group. At one point I wanted to call them “evangelical atheists” but that felt a bit too confusing. So we settled on Zealous Atheists. It’s important to point out that this group is the smallest of the four: just 11% of the nones are classified as Zealots. That was a really startling finding from doing this type of analysis - the vast majority of non-religious people don’t attempt to persuade other people to leave religion behind. That wasn’t true of Zealous Atheists - about three quarters of them have tried to convince someone else to leave religion in the prior twelve months.

When we give presentations about these results to various groups, this is the part of the talk where people lean forward in their seats and get very engaged. We think there’s a reason for this: these are the type of people that you encounter when you try to talk about religion on social media. They are quick to point out that religious people believe in fairy tales or that they don’t need to pray to Sky Daddy or they mockingly worship the Flying Spaghetti Monster. I’ve taken to calling them the Reddit Atheists — if you’ve ever spent some time in that forum, you know exactly what I mean. They are often angry, caustic, and eager to get into an argument.

What’s really noteworthy about this group is that they actually engage with religion a bit more than the Dones. About 17% attend a house of worship once a year or more, and about the same share say that they have prayed just a little bit in the prior year. We think there’s a reason for this: they still interact with religion enough to remind themselves why they dislike it so much. Maybe it’s their spouse or their parents who are still religious and they attend Christmas Eve Mass with them to be nice around the holidays. But they aren’t as far away from religion as the Dones.

Well, this is a good start toward describing the findings of The Nones Project. We plan to publish a new post in this series every other Saturday for the foreseeable future. We’ve got a ton of unmined territory in our dataset. We have a range of questions about how the non-religious make meaning, how they feel about traditional religious groups, and the religious environment in which they were raised. So, we hope you enjoy this new series and feel free to ask questions in the comments. There’s a good possibility that we can answer them using our data.

Our plan is to publicly release the data next Spring on The Association of Religion Data Archives, so that other folks can explore this data for themselves.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

The Dutch have invented an interesting word for the SBNR category: ietsism. Ietsists do not believe in a personal God, but have a "unspecified belief in an undetermined transcendent reality." The word "iets" means "something" in Dutch. An ietsist is someone who when asked whether he or she believes in God, answers, "No, but there must be something." My mother was one. Einstein most often called himself an agnostic, but ietsist is arguably a better fit.

A 2014 poll concluded that the Dutch population is 27% ietsist, 31% agnostic, 25% atheist, and only 17% theist.

It would be interesting to cross reference the four types with our political parties...