How Many Americans Are Actually Spiritual But Not Religious?

Why “Spiritual But Not Religious” Might Be More Niche Than You Think

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

It may be one of the most frequently used terms in my neck of the woods - “spiritual but not religious.” The term is one that is really hard to trace back to its origins but Wade Clark Roof’s 1993 book A Generation of Seekers definitely talked about this general idea. However, I think that Robert Fuller’s Spiritual, but Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America is probably the one single piece of scholarship that pushed that term into the mainstream. It’s used so much among folks who study the decline of religion that it has an acronym - SBNR. It’s certainly an idea that we almost accept as being true without really testing the underlying assumptions behind it.

While there are a dozen working definitions of the SBNR concept, I think it’s probably most clearly articulated by saying it’s an individual who says that they are spiritual but reject all the trappings of organized religion. This could be someone who doesn't ever go to church, but they read their horoscope on a daily basis and believe that tarot cards can help them understand the future. It could also be someone who doesn’t identify with a particular religious faith, but perhaps believes in the afterlife or a higher power. Certainly the discourse around this type of person is that they are becoming a larger share of the population. But, I wanted to test that really basic claim with data from the General Social Survey.

In 1998, for the first time the GSS asked, “To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person?” - the ARDA provides a handy little tool to just check the frequencies of those responses without having to download the data or anything. What’s interesting is that the team at GSS didn’t ask that same question again until 2006 but has asked it in every wave of the survey since that point.

The most common response over the time series has been “moderately spiritual,” with 40% of respondents selecting this option in 1998. But things have dropped from there. In 2022, just 32% of folks said that they were moderately spiritual. Meanwhile, the percentage of those identifying as “very spiritual” has increased, rising from 22% in 1998 to 26% in 2022. However, the trend line for “very spiritual” seems to be pointing downward in the last couple of surveys. I just can’t see how one could draw the conclusion that highly spiritual people are a growing part of the adult population.

The biggest shifts have occurred among those who consider themselves “slightly spiritual” and “not at all spiritual.” The percentage identifying as “slightly spiritual” started at 26% in 1998, dipped slightly in the early 2000s, but has since rebounded to the same level in 2022. Meanwhile, the “not at all spiritual” group, which started at 12%, has seen a gradual rise, reaching 15% by 2022. So, the ‘very spiritual’ percentage has increased by 4 points since 1998, but the share who are ‘not at all’ spiritual has also risen 3 points. Again, if there’s a rise in spirituality in the United States, that claim cannot emanate from this GSS data.

Having established that overall spirituality is not dramatically increasing in the United States let me take this analysis one step further by just looking at people who claim no religious affiliation. I mean, it does seem likely that there are a growing number of people who are quite literally “spiritual but not religious.”

This is certainly not a graph that represents a lot of really significant changes over time. A lot of these lines have been almost completely flat since 1998. In that first sample collected in the late 1990s, about one third of the nones said that they were “not at all spiritual” and the same share said that they were “slightly spiritual.” So two-thirds of the non-religious were also not very spiritual either. Just 12% of the nones said that they were “very spiritual” and another quarter chose the “moderately spiritual” option. Certainly not overwhelming evidence that a lot of nones have a deep spiritual side.

If you look at how things have changed over time, what’s remarkable is how little these proportions have shifted. Consider this - the nones were 13% of the population in 1998 and were 27% of the sample collected in 2022. So, a doubling in size. Yet their overall spiritual composition just didn’t change that much. In fact, not a single response option moved by more than two percentage points in either direction over the prior 24 years. So there is no evidence to be found here that the nones grew larger because of an influx of SBNR people.

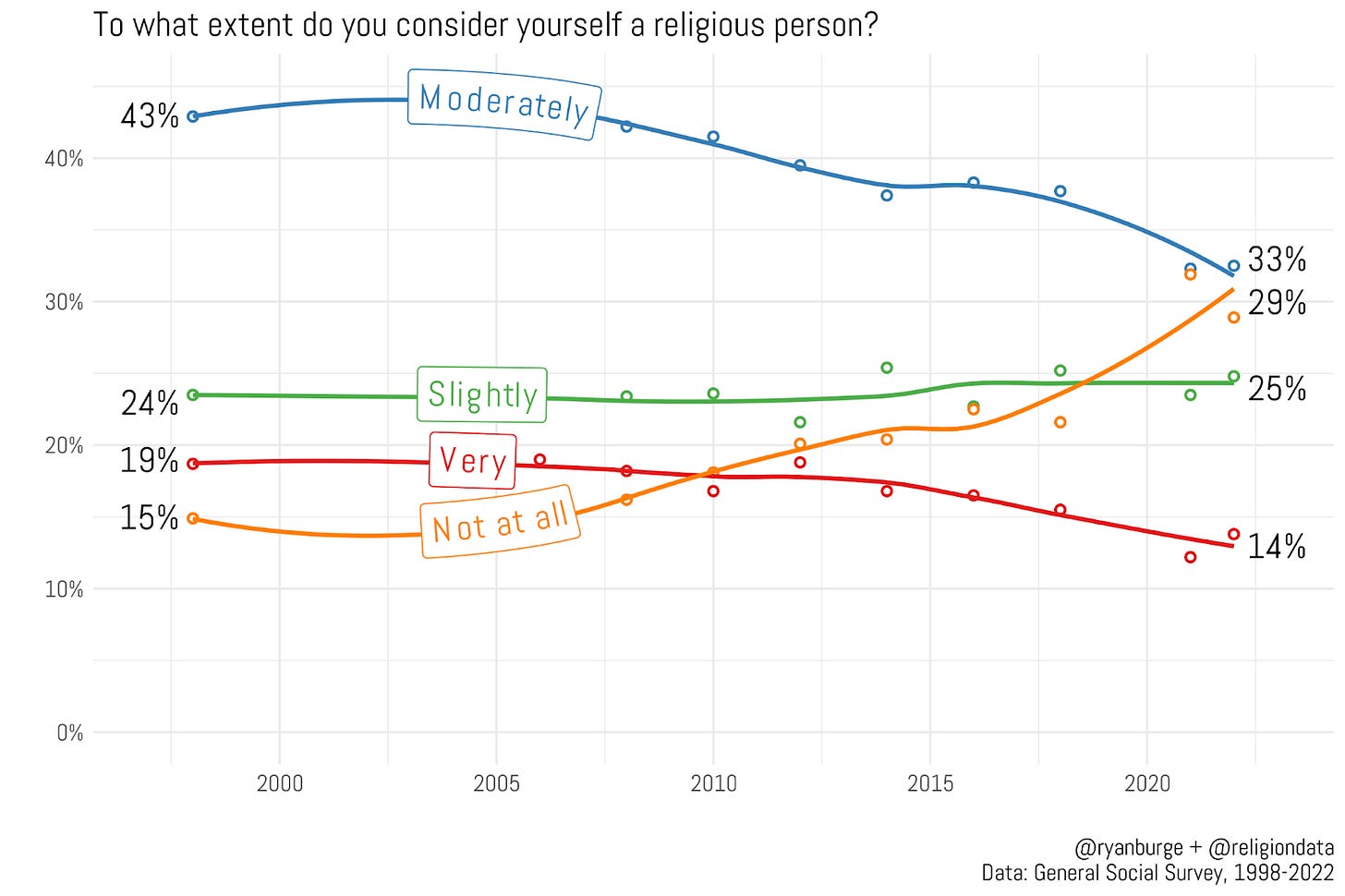

Now, of course, I do need to provide a bit more context for this by illustrating how responses to the question “to what extent do you consider yourself a religious person?” have changed over time, as well.

You can see that the most popular answer for the entire time series is “moderately religious.” In 1998, 43% of all respondents chose that option. Meanwhile, less than 20% of people in 1998 said that they were “very religious.” If you trace the lines over the last twenty-five years or so there’s a whole lot of stability around the ‘slightly’ and ‘very’ religious response options. They have moved no more than five percentage points.

There is movement on the other two options, though. For instance, the “moderately religious” contingent was 43% of the sample in 1998 and that’s now down to just 33%. At the same time the “not at all religious” group used to be the least popular at 15% but has risen dramatically over time. Now, 29% of the sample reports that they are not religious at all. A near doubling since 1998. I think it’s probably the case that the “not at all religious” response option will be the plurality in the next 5 years. Religion is certainly not en vogue in the United States in 2022, but it doesn’t look like it was even that popular back in the late 1990s.

How about we combine both of these metrics into a single visualization now to see how both religion and spirituality have shifted between 1998 and 2022.

There is some movement here between some squares in 1998 and 2022. The one that jumps out to me the most initially is the “moderately spiritual” and “moderately religious” option. In 1998, 29% of folks in the sample chose this one. In 2022, that had dropped to just 18%. Also the “very/very” square was 14% in 1998 and 11% in 2022 - a drop of three points. So that’s a 14 point decline in just those two squares alone.

Of course those losses have to be picked up in other places - where did they go? The “moderately religious/very spiritual” group jumped by four points. So did the “not at all religious/slightly spiritual” option. But there wasn’t a single square that just saw a massive increase from 1998 to 2022. Instead, I think it’s instructive to look at the four squares in the top left. In 1998, that was just 8% of the sample. In 2022, it was 19% of the sample. So, that does look like a noteworthy increase in the “low religion/high spiritual” sector. In comparison the bottom left four squares (low spirituality/low religion) only increased by five points.

But again, I just don’t look at this graph and think “wow, that top left corner is just filling up rapidly.” Using this definition, less than 20% of American adults are spiritual but not religious. It was 8% of the country in 1998. That's a half a point per year increase. It’s certainly some movement, but not at all dramatic. From my vantage point, this is still very much a niche part of the religious landscape.

Here’s an interesting extension of this question, though. I took the six large religious traditions and compared their responses to the spirituality question in both 1998 and 2022. I was wanting to see if any Christian tradition seemed especially drawn to spirituality today in a way that wasn’t true in the late 1990s.

Look at the evangelical graph in the top left. In 1998, just 28% of evangelicals described themselves as “very spiritual.” In 2022, that share was up to 46% - an 18 point increase. That really struck me, honestly. Maybe all that talk about how “it’s not a religion but a relationship” has led many evangelicals to see themselves as more spiritual. If you look at the graphs for the other Christian traditions you really don’t see anything quite that dramatic. The share of mainline Protestants who are very spiritual is up by four points, it’s 10 points for Black Protestants and 2 points for Roman Catholics. But nothing close to that shift among evangelicals.

And, I wanted to point us back to the non-religious too, for just a second. None of those numbers have shifted in any significant way since 1998. What makes that just really fascinating to me is that the overall composition of nones probably changed more than any other religious group during this time period. Nones aren’t more spiritual today than they were twenty years ago. About two-thirds of them say that they are “not at all” or “slightly” spiritual.

I hope that this bit of data analysis helps us to calibrate what this idea of “spiritual but not religious” is really all about. Yes, it’s a growing share of the American religious landscape. But even today, less than one in five adults fit these criteria. Also, it doesn’t appear to be the case that the SBNRs are really religious refugees who left a church for the word of non-religion. It’s something to keep an eye on but the SBNRS are certainly not going to be a majority of Americans at any point in the near future.

Code for this post can be found here.

Two observations. The description of spirituality without formal affiliation has existed in other forms for a long time. Those of us who were Scouts remember #12 of the Scout Law. A Scout is Reverent. They have religious medals that can be earned by performing what each denomination requires, much like a merit badge. But no affiliation is also acceptable. Reverence in some form is required.

The trends in spirituality parcelled out over each faith tradition over 25 years has to be taken in the context of shifts in membership during that interval. The Evangelicals may be more spiritual now because the ones who were less spiritual became their sources of attrition. Much like WB Yeats' observation as Irish Revolutionaries were sorting themselves out in his era. "The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity."

Speaking entirely anecdotally, I do think that most of the Canadian Evangelicals that I have pastored over the past fifteen years would have denied that they were religious but affirmed that they were spiritual. "I'm not a religious person" is something I hear a lot from the most religiously motivated folks in my circles!