Is Divorce the Next Front in the Culture War?

Is it too easy to dissolve a marriage right now?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

When someone says the term “Culture War,” the first issues that usually come to mind are access to abortion or same-sex marriage. These are two of the most well-known ‘social issues’ in American religion and politics over the last several decades. Interestingly, both areas have seen a lot of newsworthy events in recent years - the Supreme Court decision Dobbs v. Jackson essentially gave states the power to regulate abortion access and Obergefell v. Hodges made same-sex marriage legal in all fifty states.

However, there are a number of secondary issues in the culture war that don’t come up as much - like marijuana legalization or regulation of pornography. There are certainly some dust ups about both from time to time but they don’t grab headlines like abortion or gay marriage. However there’s another issue that is starting to creep into the mainstream discourse - divorce. For instance, NPR ran a story last year with the headline, “Conservatives in red states turn their attention to ending no-fault divorce laws.” So, there is certainly some effort among religious and political cultural warriors to rethink how divorces are granted in the United States.

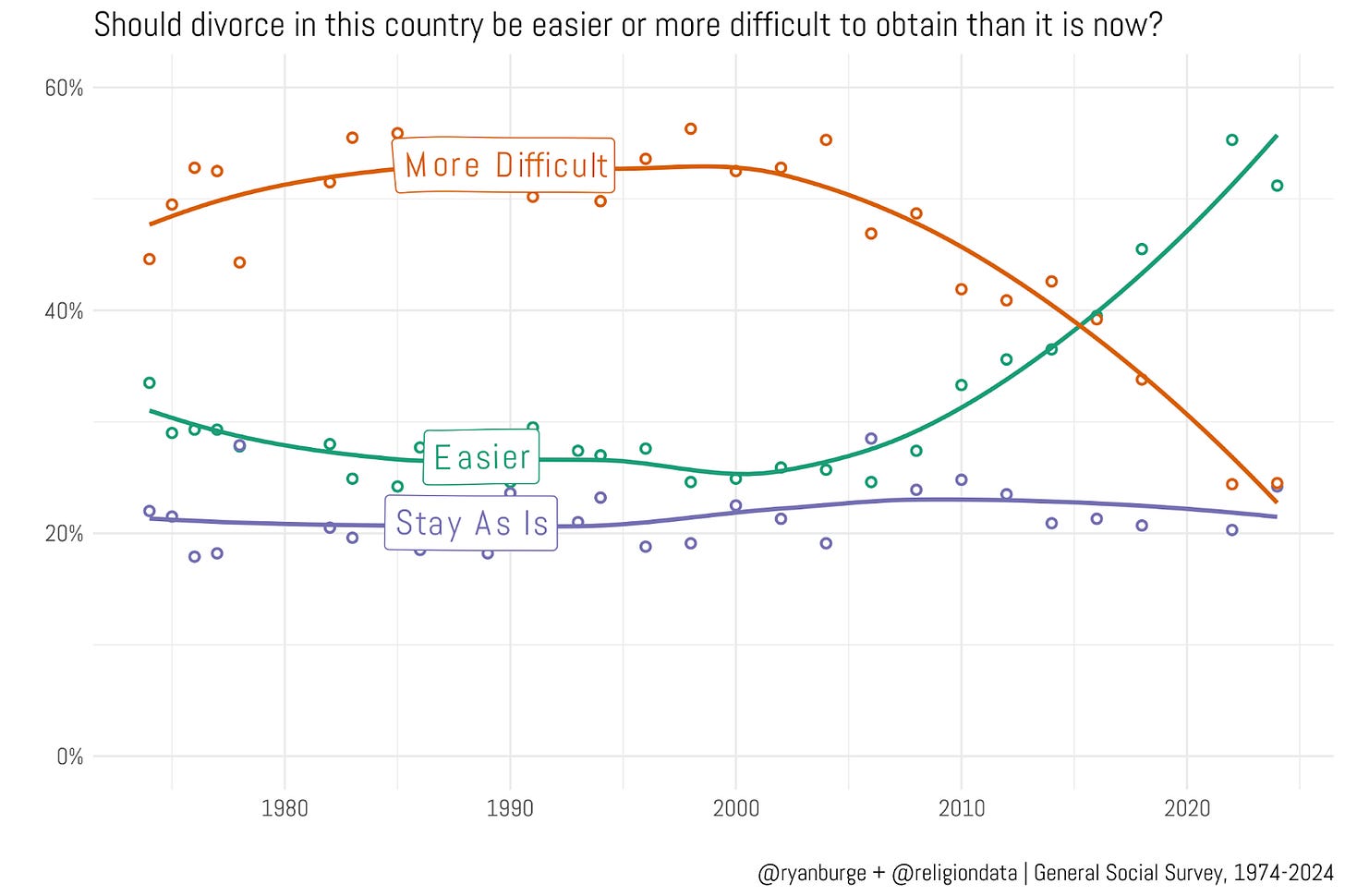

The General Social Survey (which is hosted on the ARDA) has been asking a question about divorce since 1974: “Should divorce in this country be easier or more difficult to obtain than it is now?” It’s a perfect window into how Americans have been thinking about the topic over the last several decades and whether those views are shifting.

The best way to describe opinion on divorce between the mid-1970s and 2000 is stasis. A little less than 50% of Americans thought it should be more difficult. Between 25-30% thought it should be easier and about 20% thought it should stay as it is.

But then look at what changed in the last twenty years - Americans became a whole lot more permissive toward divorce. The share who said it should be easier to get a divorce was 29% in 2006. In 2024, it was up to 52%. Most of that shift came from the ‘more difficult’ crowd which dropped roughly twenty-five percentage points during the same time period. The ‘no change’ crowd barely shifted.

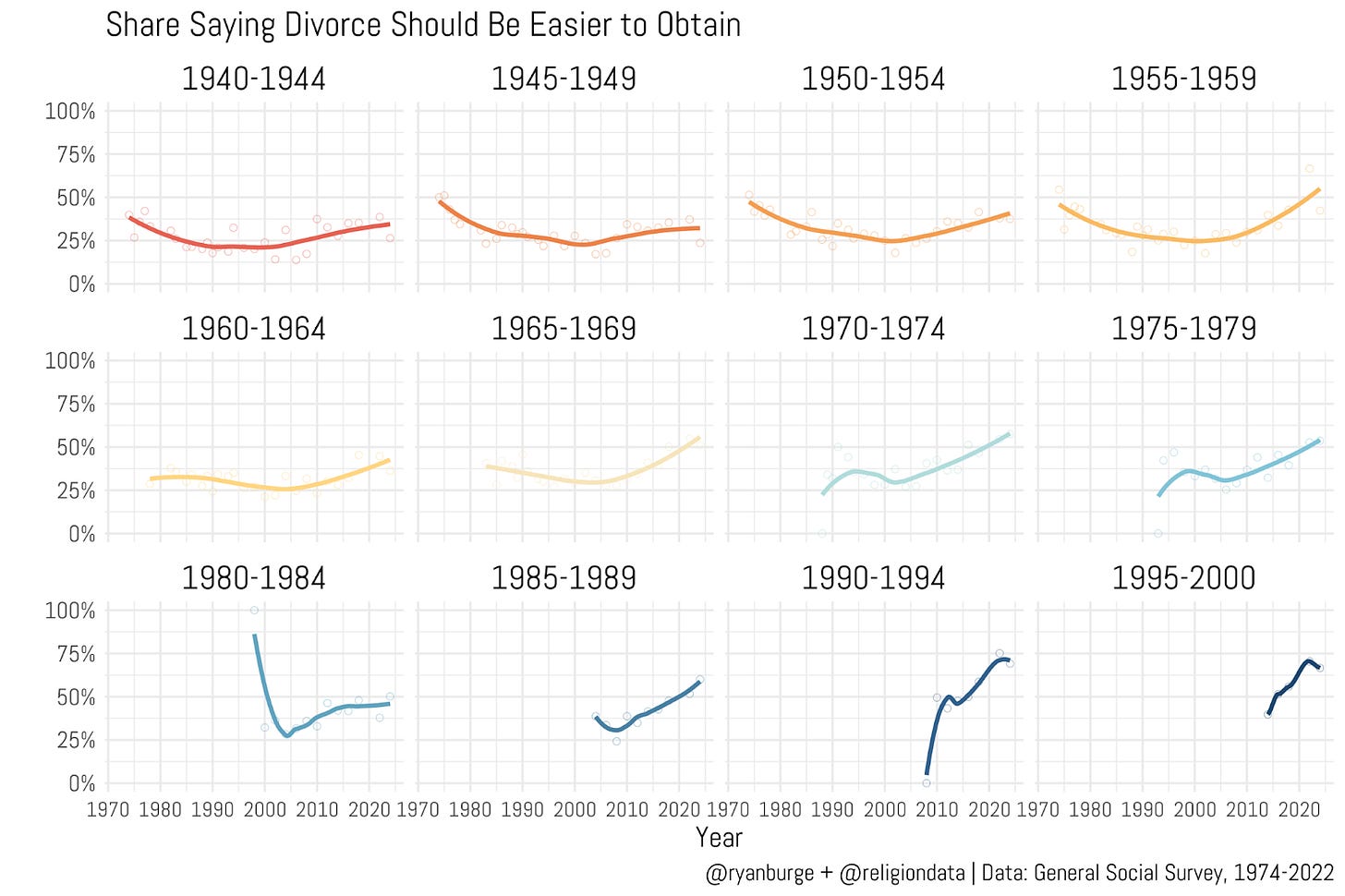

There’s no doubt that the average American is more permissive of divorce today than the average American from the early 2000s. But how did that shift happen? Are older people changing their minds? Is it generational replacement? Let’s do a cohort analysis.

The top row is folks who were born in the 1940s and 1950s, and the shape of their lines looks very similar to each other. When they were younger, they took a more permissive approach to divorce. Then, as they moved into middle age, they were less likely to say that it should be easier to get a divorce. But they have reversed course in the last two decades. Now, they are as permissive today as they were in the 1970s.

The pattern across the second row is completely different. For folks born in the 1960s and 1970s, their opinion of divorce didn’t change a lot for the first couple of decades. However, something happened in the mid-2000s which led to a huge shift toward easier divorces. For those born between 1965 and 1974, support for easier divorces basically doubled. That’s astonishing.

It’s hard to make sense of the bottom row. There aren’t a lot of data points for the youngest cohorts, but I think I can say that the evidence is pointing towards young adults becoming much more permissive as time passes.

Overall, this appears to be a story of generational replacement. Older folks are more conservative regarding divorce. Younger folks are more liberal. As time passes the top rows are replaced by more people in the bottom rows which moves the aggregate number.

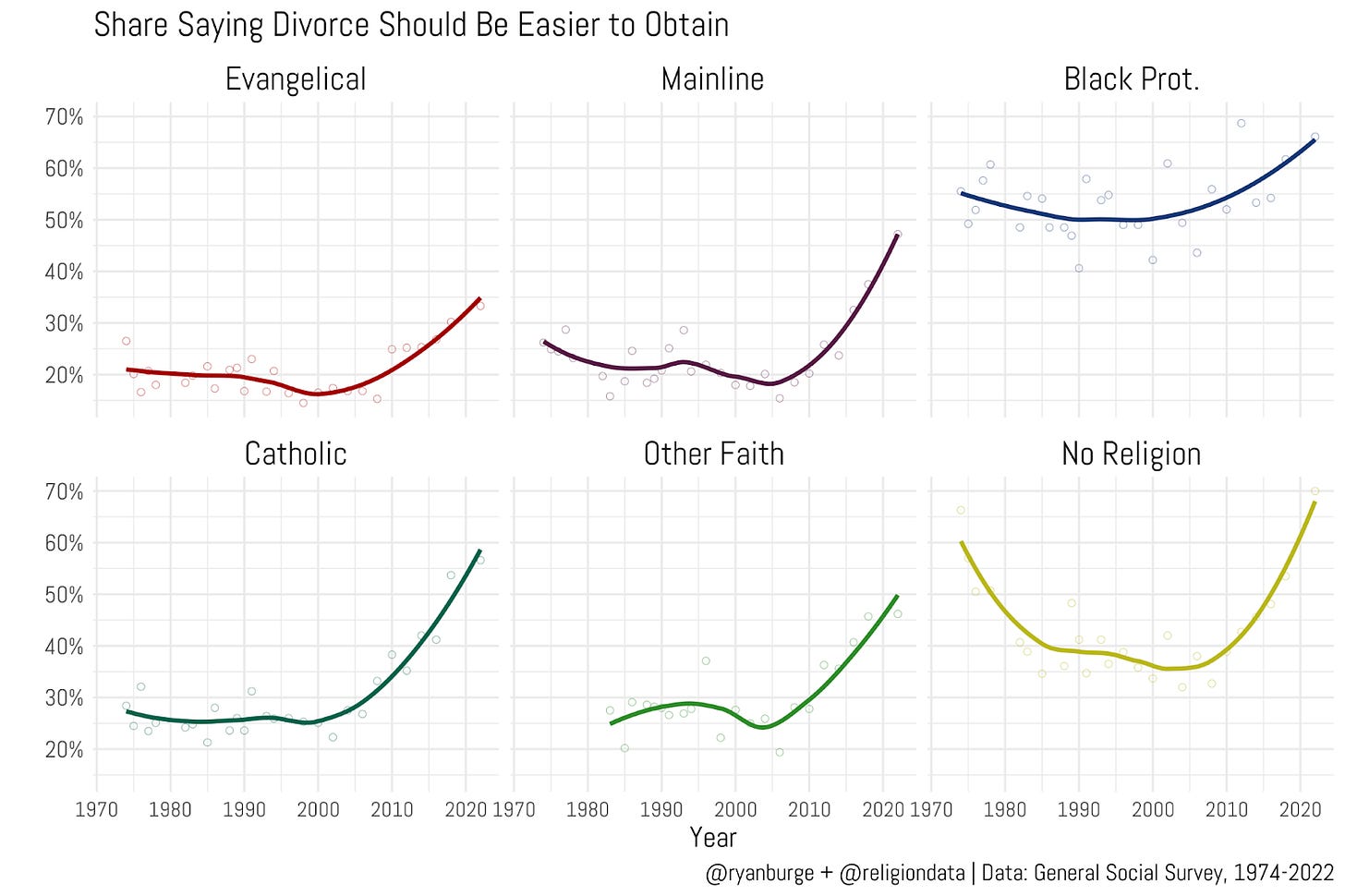

It’s undoubtedly the case that religion can influence one’s views on divorce. In the Christian tradition, divorce is generally frowned upon, if not largely forbidden. Other religions tend to be somewhat similar in this regard, with Judaism seeing divorce “as a fact of life, albeit an unfortunate one.” So there’s ample reason to believe that religious Americans should have a different view of the issue than the non-religious.

It’s really noteworthy how the three majority white Christian traditions (evangelical, mainline, Catholic) have a very similar trajectory. Between the mid-1970s and the mid-2000s there was no shift at all. However, by 2005 the lines began shooting up for each group. Today, about a third of evangelicals think divorce should be easier; for mainline Protestants, it’s 48%, and for Catholics, it’s 58%.

Notice how much the Black Protestant line deviates from the other Christian groups, though. The Black Church was more permissive of divorce in the 1970s than the mainline Protestants have ever been. And Black Protestants have only moved in a more permissive direction in the subsequent decades. Now two-thirds believe that divorce should be easier.

I do want to highlight the non-religious result, though. In the 1970s, the nones were much more permissive of divorce. Then, the belief that it should be easier dropped noticeably to about 35%. Then it shot back up from there, and nearly 70% of the non-religious think divorce should be easier to obtain. The only group that is even close to that percentage is the aforementioned Black Protestants.

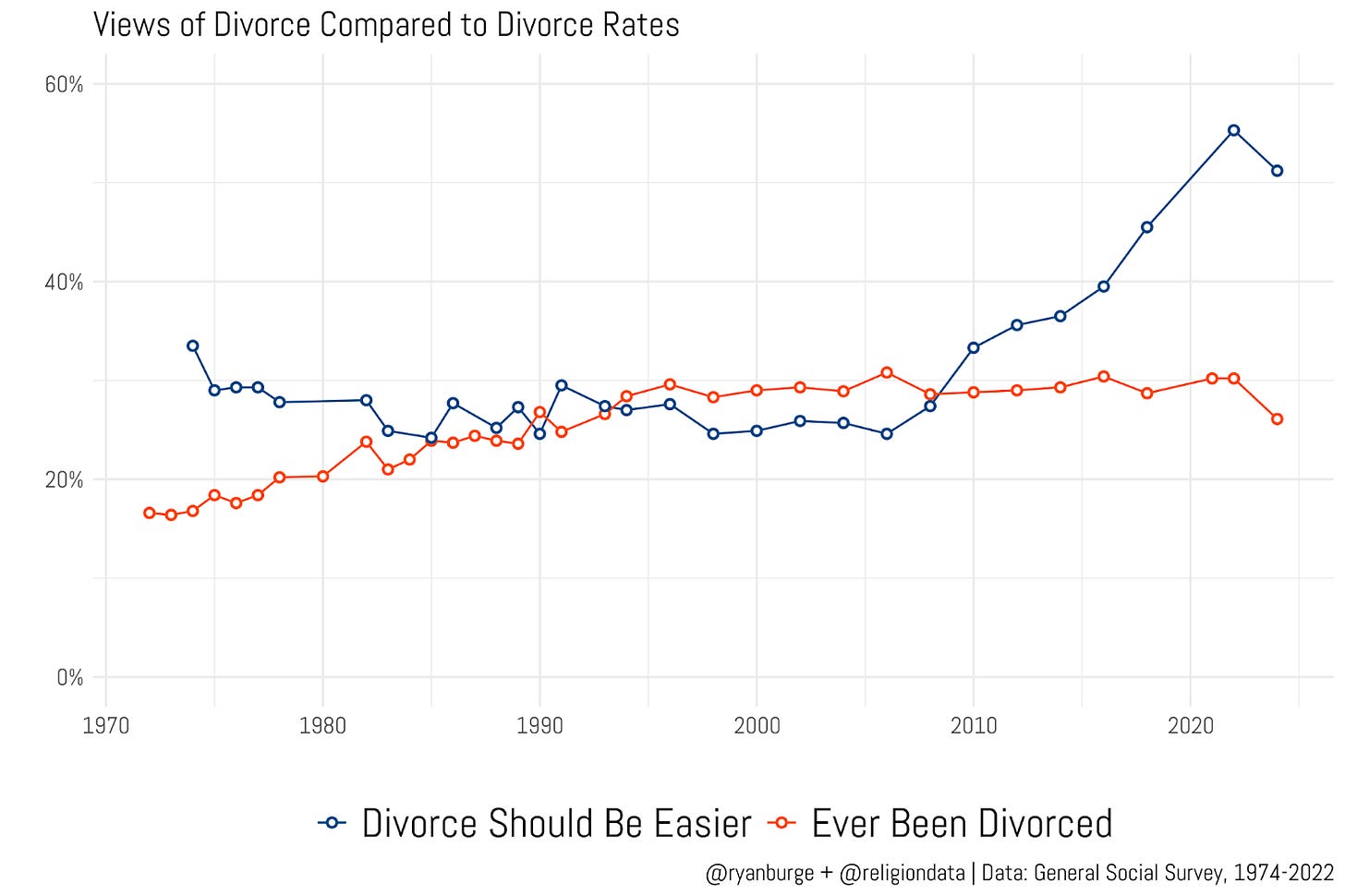

There’s one last factor lingering behind the scenes that could have a huge impact on these numbers - the share of folks who have gotten a divorce has increased significantly since the 1970s. Well, the General Social Survey has been asking about marital status since its inception.

To calculate the divorce rate, I removed folks who had never been married and then calculated the share of ever-married individuals who had been divorced at some point. There’s been a pretty modest increase over time. For instance, in the early 1970s it was around 18%. It rose to nearly 30% of the sample by the mid-1990s and has kinda stuck at that level for the last few decades.

Meanwhile, support for making divorce easier tracked pretty well with the divorce rate from the mid-1980s through the late 2000s. But then the lines began to diverge. More specifically, views of divorce became more permissive even as the divorce rate stayed steady. In other words, it seems pretty unlikely that opinion change was driven by a huge surge in people who wanted to get a divorce.

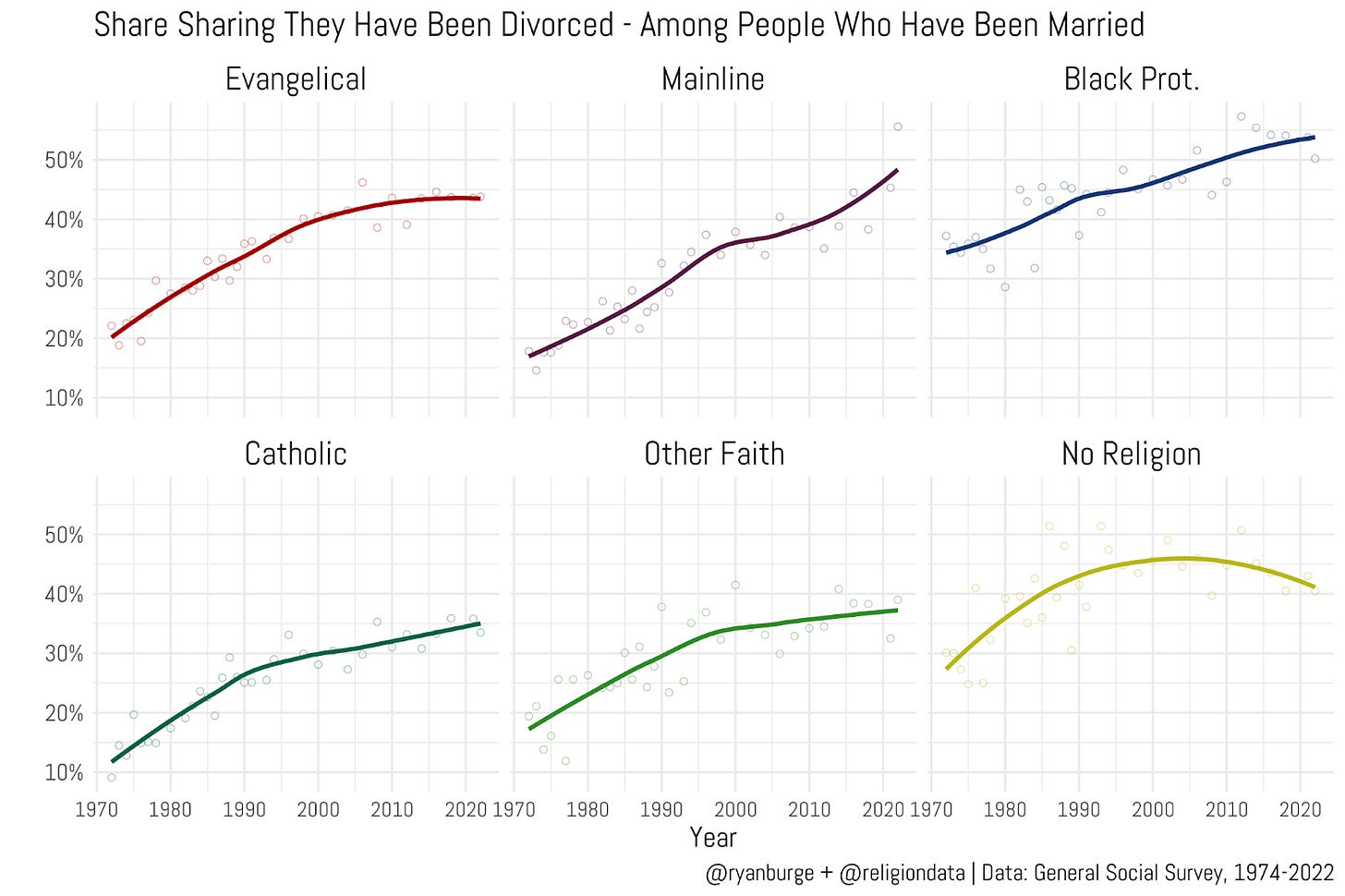

What about the divorce rate in specific religious traditions? Well, to put it bluntly - they are up. A lot.

The General Social Survey data indicates that in the early 1970s, only about 20% of evangelicals who had been married had experienced a divorce. Which was just slightly higher than the mainline but much higher than the Catholics (which reported a divorce rate of just above 10%).

But all traditions have seen big increases in divorcees with the passing of each successive decade. For instance, divorce rates among evangelicals are between 40-45% now. But that’s largely flatlined in the last ten years or so. Among mainline Protestants, the number keeps increasing and is near 50%—an all-time high. However, Catholics are the big outlier. Among Catholics who have walked down the aisle at least once, only about 35% are divorced.

The nones really stand out to me, though. Their divorce rates rose quickly in the 1980s and 1990s and hit a peak around 2000 at 45%. But the share of the non-religious who have been divorced has actually receded just a bit in the last couple of years and is now down to 40% or so. That’s lower than evangelicals, actually.

But a big caveat here - I removed the people who have ‘never been married’ from the sample before I did the analysis. In 2022, only 18% of evangelicals had never been married compared to 40% of the non-religious. Which means that far fewer nones get married than evangelicals. But when a “none” gets married the likelihood of them getting a divorce is actually slightly lower than most Christian groups. That’s something worth thinking about.

So, a few points in summary.

The general public is far more permissive of divorce today than it was in the 1970s. But almost all that movement has happened in the last 20 years.

The reason for the shift is probably generational replacement. Older, more conservative folks have died and are being replaced by younger people who tend to be more accepting of divorce. However, this change is probably not being driven by a change in divorce rates.

When it comes to religion, evangelicals are the least supportive of easier divorce while mainliners and Black Protestants are the most supportive. The views of the non-religious have shifted big time over the last few decades.

Calculating divorce rates across religious groups is really hard, because the nones tend to not get married at nearly the rate of religious folks. But when the nones get married they are essentially no more (or less) likely to get divorced than Protestants.

Looked at in totality - I just don’t see a huge appetite across the American population for policy changes on divorce. Yes, there are some loud voices who want to end “no fault divorces,” but that is not at all reflected in the aggregate data. Folks seem to take a laissez-faire approach to the topic, even people of faith.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

I’m a lawyer who’s more generally conservative (libertarian-flavor) and I agree with you on this point!

I wonder if the reactions on this point have more to do with the difficulties with sorting out financial and child care issues in divorce situations - actual difficulties and perceived senses of fairness or unfairness in matters involving child custody, support, division of assets, etc. Back in the bad old days of ‘fault’ divorce, it was generally more tolerable to a general public watching mostly from afar that the ‘bad’ spouse was dealt with punitively and the ‘innocent’ spouse was treated more positively.

My biggest concern with easier divorce is the effect on children, especially as easier divorce leads to multiple mixed families, step-siblings, wrenching changes in financial and other circumstances for children, who are often shuttled between parents in joint-custody situations, with both parents vying for the kids’ sympathy and loyalty.

Regardless of the legal impediments or lack thereof, married couples should think thrice (or more) about the potential effects on the children and less often about their individual ‘happiness’ in situations in which there is no overt infidelity or physical or mental abuse.

I’ve know a fair number of kids over the years - starting with friends when I was a teen and on through children of friends and of our own children - where the parents divorced at sensitive times for the children for no apparent reasons other than they had ‘grown apart’ or ‘wanted to do their own thing’ or even ‘wanted a better lover’…Very tough on these kids - unsettling to the kids into many ways, confusing about themselves and everything they’d believed about their families, etc.

I know there are situations where divorce makes sense even when children are involved, and I am certainly no enemy of relatively liberal divorce laws.

Abortion and divorce are both indications of individual and a societal failure to understand the difference between a contract and a covenant----a failure to think of possible consequences first, then act accordingly. Apparently we "all" live in Erica Jong's "paradise" now.