How Much Did Evangelical Identification Shift Between 2020 and 2022?

It may be the most contentious word in the world of religion right now—evangelical. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I hear this word spoken nearly every day of my life. Reporters want to ask me about the voting patterns of evangelicals. Audiences for my talks want to try and understand the concept better. Trolls on social media try to pick apart how I operationalize the term in my research.

More and more, I’ve come to a simpler approach to this whole topic. A survey asks people, “Do you consider yourself a born-again or evangelical Christian or not?” If they say yes, that’s good enough for me. It’s not my job to police words. If an individual who never goes to church says that they are evangelical, that’s just fine. Or if a Catholic or Muslim reports an evangelical identity, I have to figure out why they said yes to that kind of question.

Building on that, I now have a tremendous opportunity, thanks to recently released data, to understand the term ‘evangelical’ at an individual level. The Cooperative Election Study surveyed about 61,000 people in 2020. Then, two years later they recontacted 11,000 of them and asked them a lot of the same questions as the prior instrument.

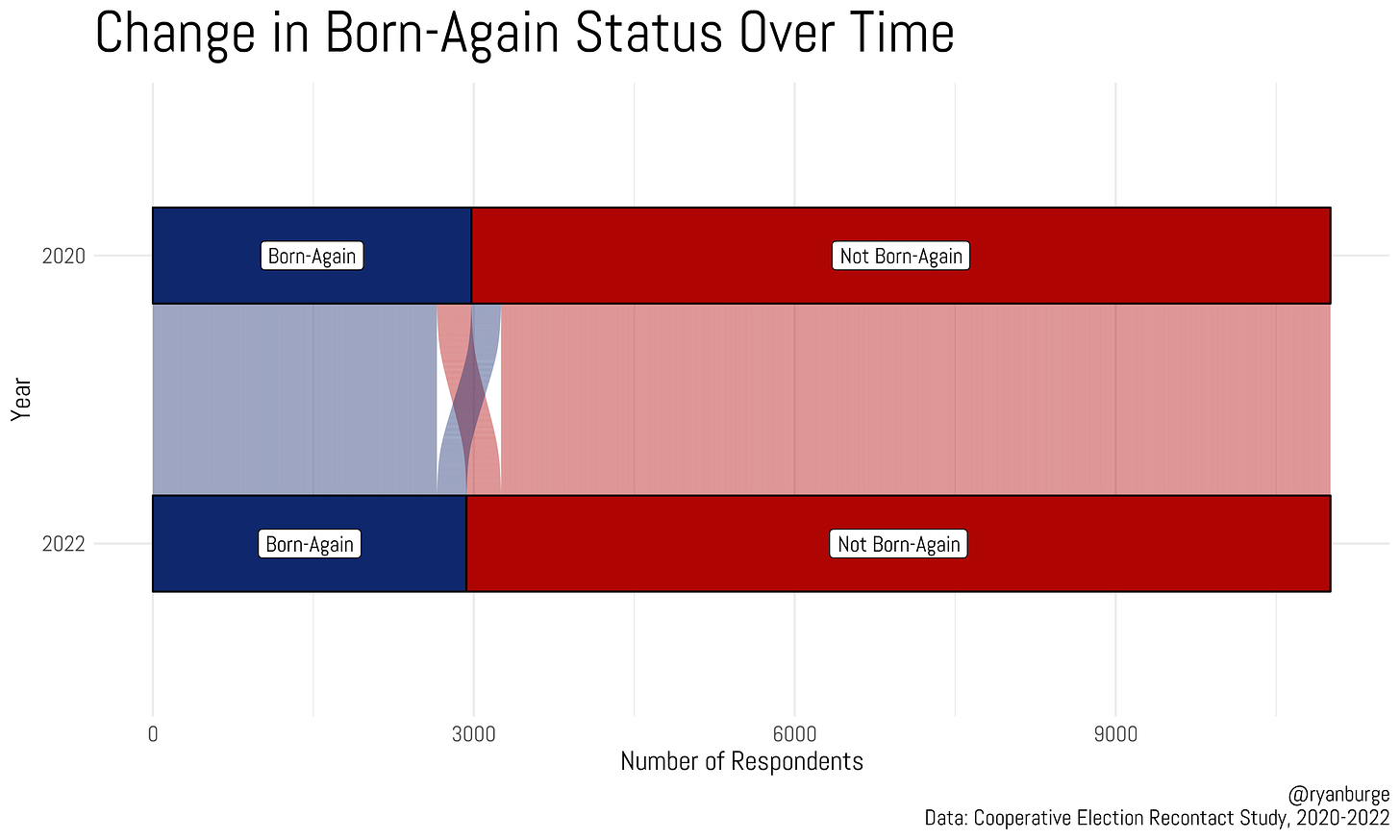

Well, guess what they included in both surveys? A question about evangelical self-identification. Here’s how people’s responses to that question changed over that 24 month period of time.

Well, that graph is pretty boring right? This is what’s frustrating for people who don’t work with data regularly—there’s rarely a huge 'a-ha' moment. More often than not, the shifts are subtle when tracking people over two years. In this case, about 94% of the sample did not change their evangelical self-identification between 2020 and 2022.

But for those who did shift from being born-again to not born-again or vice versa, is there anything in the data that points to causes for those changes? Let me walk you through what I found.