Does Religion Generate Higher Levels of Self-Reported Well Being?

A look at 25 countries around the world.

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

I've got some pretty fun data to work with today - it's got a great name: "The Many-Analysts Religion Project," and it asks a battery of religion questions from folks in twenty-five countries around the world. Although it was fielded in 2019, it was just added to the Association of Religion Data Archives (the ARDA) in the last couple of weeks. After exploring the codebook and noticing the range of unique questions on religious practice, I knew I had to dig deeper. There's a solid mix of countries - places like Turkey, Israel, Morocco, India, China, Canada, Brazil, and the United States. And the survey asks a bunch of nuanced questions about religion beyond the typical measures of religious attendance.

Let me start with this fun one - it asks people how they would describe themselves: atheist, not religious or a religious person. I especially like the fact that the survey makes a clear distinction between being atheist vs non-religious. In their recent book, Secular Surge, Campbell, Layman and Green drive home the distinction between those groups. Atheists and agnostics are considered secular folks; they don't have a religious worldview. It’s been replaced with a framework based on logic, reason, and science. On the other hand, non-religious people have shed the religious perspective but have not replaced it with anything else. Here’s how respondents in all 25 countries answered that question.

In terms of the largest concentration of atheists, there are two top contenders - China and Spain. Nearly half of the sample from each country chose the atheist option. Then, there are a number of countries that have an atheist population that is at least one-third of the sample including Turkey, the UK, and Japan. In the United States, about 15% of folks said that they were atheists - that’s in the same general neighborhood as countries like Brazil, Australia, and Morocco.

What countries are the most religious in this survey? Undoubtedly it’s India. Just 3% of Indians describe themselves as atheist. In contrast, 83% say that they are religious. That’s more than twenty points higher than the next country in line - Romania at 51%. In this data there are only a handful of countries where the share who identify as religious is at least 50%. That list includes the aforementioned Romania and India along with Morocco and Australia. There are a few in the forties, though - Ireland, the United States, Brazil and Croatia.

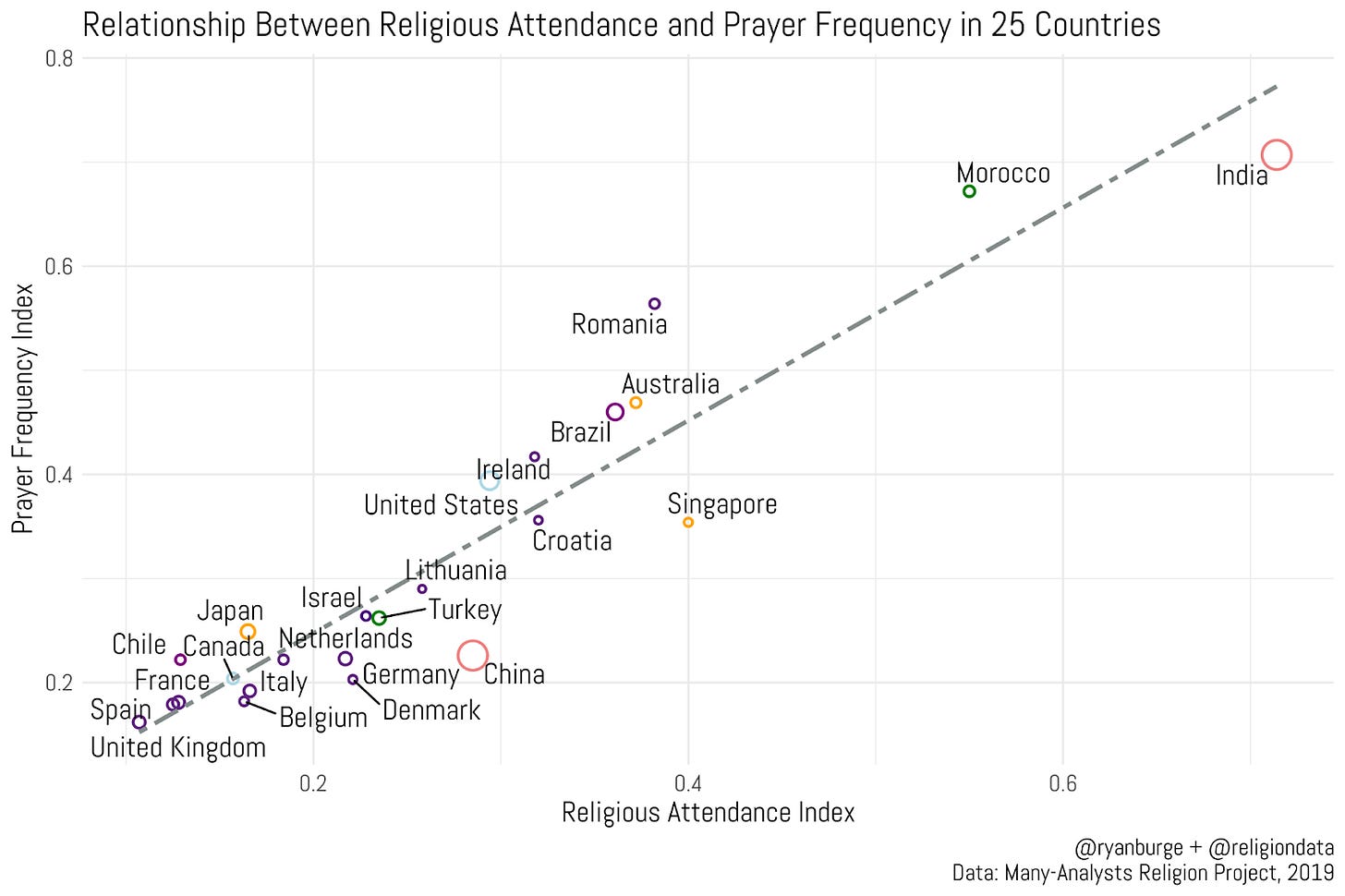

While understanding religious identity is important, analyzing behavior gives a fuller picture of religious life. Let’s explore questions on prayer frequency and religious attendance. I calculated the mean for each metric for all twenty-five countries and then put together a scatter plot of those values.

Of course there are a lot of countries that are concentrated in the bottom left corner of the graph - they score low on both metrics of religious behavior. There are a lot of European countries here - the UK, Spain, France, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. From these two measures, they honestly look pretty indistinguishable. There are a few countries on the continent that are more religious though. Lithuania scores noticeably higher on both questions but Romania is easily the most religiously active country on the continent.

The two big outliers are Morocco and India. They are the only countries out of 25 that score at least .4/1 on the religious attendance index and .6/1 on the prayer frequency metric. What I was also struck by is how few outliers appear in this data. There are a couple, though. The Romanians seem to pray significantly more than they attend church. The respondents from Singapore are the opposite - fairly high religious attendance but lower prayer frequency.

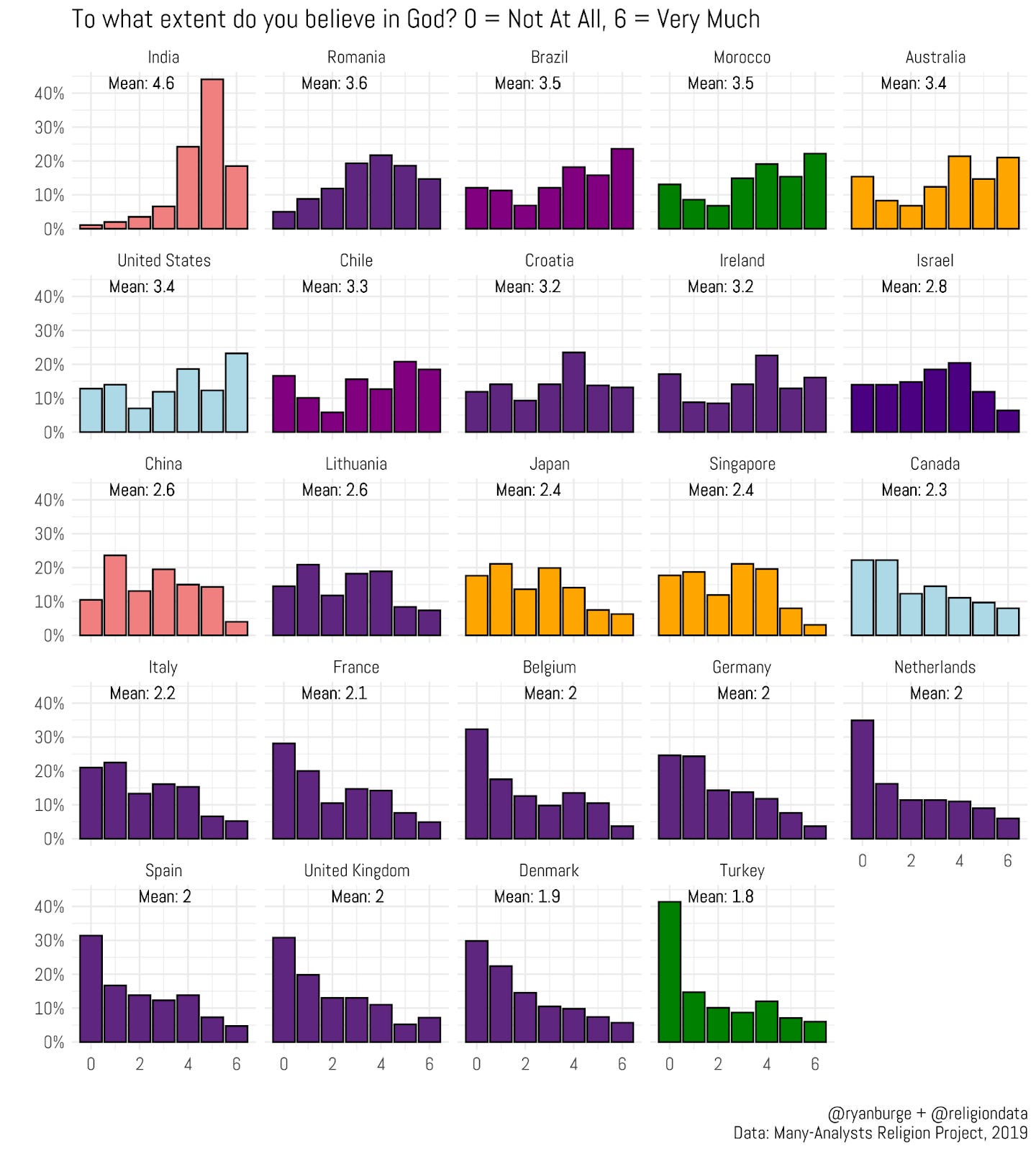

There’s also a belief in God question, that asks folks to rate their belief in God on a scale that runs from 0 (meaning they don’t believe in God at all) to 6 (they believe in God very much). Here’s the distribution of scores for all twenty-five countries and I also sorted the graph in descending order on the mean score.

Again, India is the most religious here - they are a full point higher than the Romanians. The distribution of the Indian scores really stands out - 44% of them chose 5 out of 6 on the scale. In total, 63% of Indians gave a response of five or six on this question. Then, there are a whole bunch of countries that are clustered about 3.5 out of 6 on this scale. That’s places like Brazil, Morocco, Australia, and the United States. The mean score for the entire sample on this question was 2.7, so the United States is significantly higher than the average respondent.

I tried to color code these countries based on the general region and you can see a whole lot of purple in the bottom half of the graph - these are countries in Europe. There were a whole bunch who scored right around 2 out of 6 on this question about religious belief. Among the Dutch, 35% said that they had no belief in God at all. It was 32% of Belgians, 31% of Spaniards as well as those from the United Kingdom. The only country that scored lower on this metric was Turkey at 41%.

There was also a question about belief in an afterlife. To simplify these I divided responses into three buckets - no belief in the afterlife at all, an ‘in between’ belief, and those who very much believed in life after death.

There’s not a whole lot of belief in an afterlife in a huge swath of Europe. Just 8% of Belgians and Spaniards say that they ‘very much’ believed in something after this life. A whole bunch of countries were at 12% - France, Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. However, somewhat surprisingly - the country that had the least belief in the afterlife in this sample was Italy. Just 4% of them gave the top response on this question. Although, to be fair a clear majority of Italians put themselves between the extremes on this one (57%).

There was a grand total of one country where a majority said that they ‘very much’ believed in life after death - that was Morocco at 72%. I do find the comparison between Canada and the United States pretty interesting in this graph. Among Americans, 33% very much believed in an afterlife, compared to 19% who said ‘not at all.’ In comparison, it was 16% and 32% respectively for Canadians. Nearly the opposite distribution.

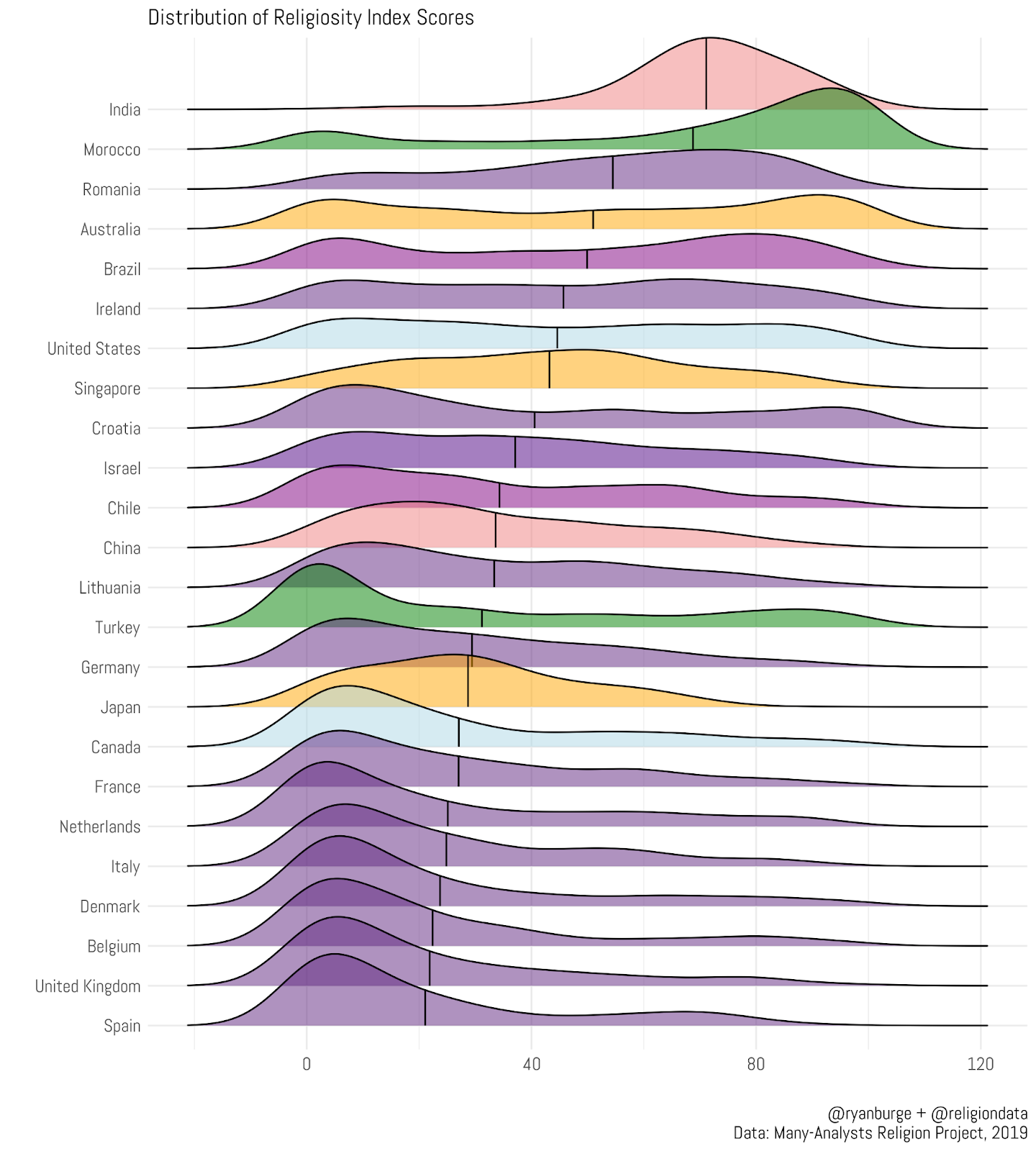

But to simplify this for the next bit of analysis, I combined seven questions about religion to create a religiosity index. These questions touched on religious behavior, beliefs and belonging. The scale runs from 0 (meaning not at all religious) to 100 (meaning very religious). Here’s the distribution of those scores among all twenty-five countries. I also denoted the mean for each country with the vertical black bars.

After looking through the prior graphs, it should come as no surprise that the two most religious countries in this data are India and Morocco. Then, there’s a huge gap before we get to Romania. Then, the gaps between the mean scores for the countries become pretty small. However, you can still see that dark purple pattern at the bottom of this graph. Those countries that score the lowest on this metric are undoubtedly in Europe. From this view, there’s not a whole lot of difference in the religiosity of the country that’s seventh from the bottom (France) and the very bottom (Spain).

I do think taking a look at the distributions can be interesting, though. For instance, you can clearly see that while a huge chunk of Turkey is not at all religious, there’s a little hump on the right side that’s north of 80/100. That’s also the basic pattern in Croatia, too. Then there are countries that are relatively flat across those ridges. This is what shows up in the American sample, as well as Singapore and Ireland, too.

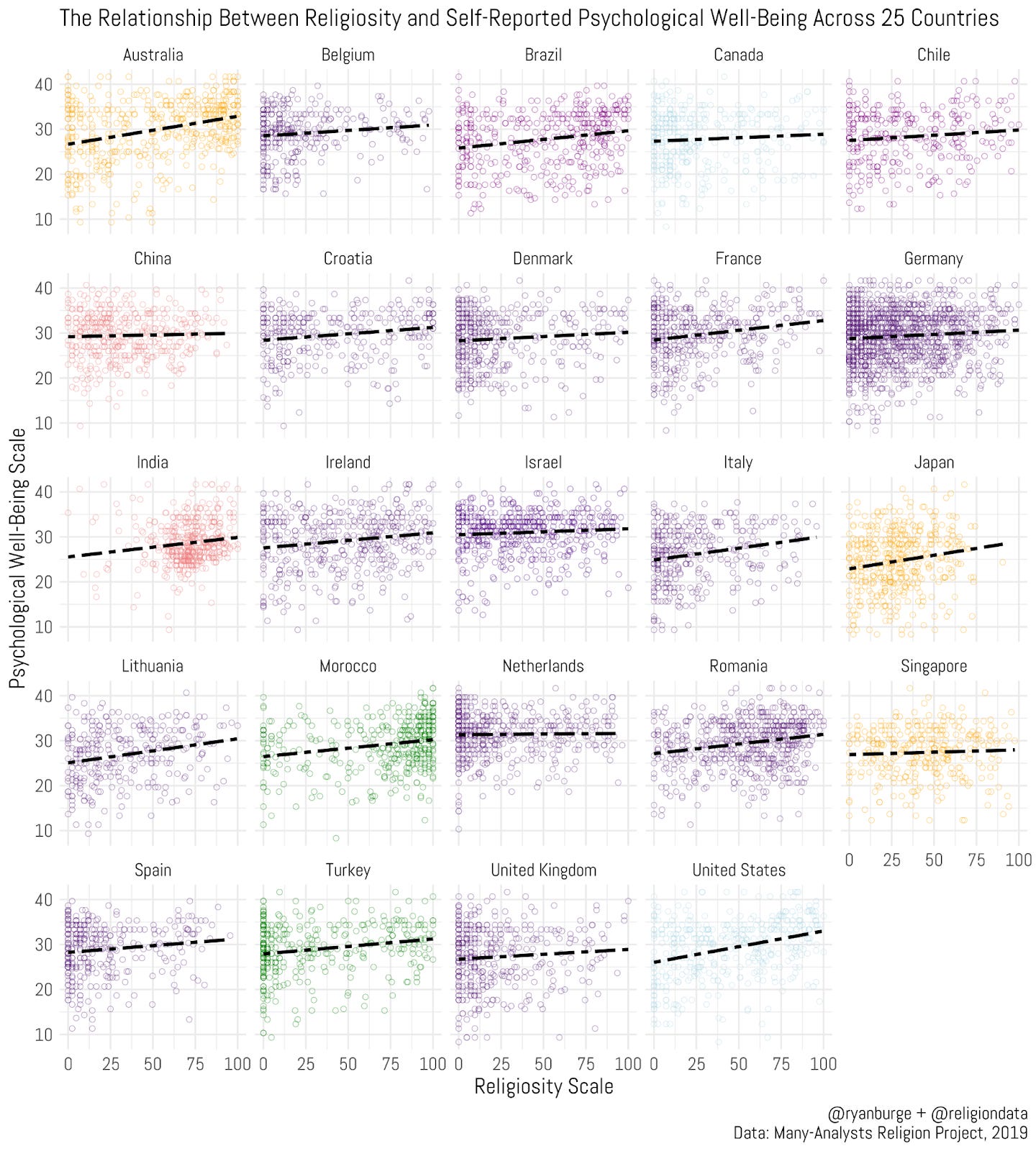

In addition to the religiosity scale, I also added together a bunch of psychological questions like: How much do you enjoy your life? And To what extent do you feel your life to be meaningful? It was a total of six questions that were summed together and transformed into an index that ran from 0 to 100, with higher numbers indicating a greater degree of self-reported psychological health. Here’s how the religiosity index correlates with the psychological index in all 25 countries.

The trend lines for a lot of these countries are relatively flat, indicating a very weak relationship between religiosity and self-reported psychological well-being. That’s evident in Croatia, Germany, China, Israel and the Netherlands. But there are other instances in which the lines do seem to point upward, which would indicate that folks with higher religiosity scores also have a greater degree of self-reported psychological well-being. The United States jumps out here, so does India, and Japan.

But I wanted to visualize the magnitude of those effects in a different way so you could understand the relationship between these variables in a more precise way. So, this is the result of a linear model that tries to predict a change in self-reported psychological well-being with a single independent variable - the religiosity index across all twenty-five countries.

First, let me speak broadly about the relationship between these two variables. In seven countries, there is no statistical relationship. That includes places like the Netherlands, China, Singapore, Canada, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Chile. There are 17 countries with a positive relationship between religiosity and self-reported psychological well-being. There is not a single country out of these twenty-five where there is a negative relationship between religion and well-being, though. That’s important to note.

The country with the most robust relationship between religiosity and increased feelings of psychological well-being is the United States. But let me spell out just how strong that relationship is based on this simple model. For every ten point increase in religiosity in the United States, the corresponding increase in self-reported psychological well-being is about .8 on a scale that runs from 0 to 100. That means that in order to increase well-being by 1%, there would need to be a 14% increase in religiosity. In other words, yes religious people tend to report higher feelings of well-being, but it’s an incredibly marginal difference.

As a social scientist who studies religion, I’m not just interested in measuring the overall level of religiosity. I am also concerned with how changes in religiosity can also impact other parts of the human experience. Here, there’s a very small positive impact on self-reported mental well-being in some countries. In other parts of the world, there is absolutely no connection at all. That’s what makes this work great - almost no social forces are universal across different continents and cultures. There is always more to explore and learn about the social world on Planet Earth.

Code for this post can be found here.

Overall, this is really interesting, great work. In particular, it really highlights that India is a world unto itself.

But another one that stands out strongly to me is Turkey. In fact, it stands out so strongly that it makes me question the data there. From everything we know elsewhere, Turkey should really stand out as being a more religious country than Western Europe. But here it appears to be less religious than Belgium. Something isn't adding up.

For example, Turkey is run by an Islamist party that rose to power democratically, overcoming various secular elements of its constitution to do so. There are lots of other anecdotes to suggest that, while Turkey isn't as religious as the Arab world, it's still a fairly pious Muslim country. But we also know the country has a sharp divide, that the Turkish Republic has its roots in the hard secularism of Kemal Ataturk, and that Kemalist ideas still hold sway over a large swathe of the population, especially in the urban cores of Istanbul and other parts of Western Turkey. So what it feels like is that, with that sharp divide, the more pious part of Turkey's population was under-sampled here.

For the record, here's the description of the sampling:

"Participants were recruited from university student samples, personal networks and representative samples accessed by panel agencies and online platforms (MTurk, Kieskompas, Sojump, TurkPrime, Lancers, Qualtrics panels, Crowd-panel and Prolific)."

Do you ever think that the evangelical emphasis on Christianity as “not a religion, but a relationship” could impact these surveys in any way?