Do You Believe in Miracles?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

About a year ago, 60 Minutes ran a piece by Bill Whitaker where he visited the town of Lourdes in Southern France. It’s become a pilgrimage site for people who are seeking a divine healing from their infirmities. Each year, over three million souls make the trek to bathe in the water of the natural spring and participate in the rituals that could possibly lead them to a cure for what ails them.

In its 160 year history as being a site of supernatural healing, the Catholic Church has recorded a total of seventy miracles. The Church has an incredibly detailed process as to how they arrive at such a stunning conclusion. The criteria for what they define as a miraculous healing is incredibly rigid and they require that dozens of physicians review the medical records of each potential case of healing.

The most recent officially declared miracle was of Sister Bernadette Moriau. She indicates that after visiting Lourdes and returning home in 2008 that God healed her of a condition called cauda equina - a debilitating disease that impacts the nerves and the lower spine. It took ten years for the Catholic Church to officially declare her divinely healed.

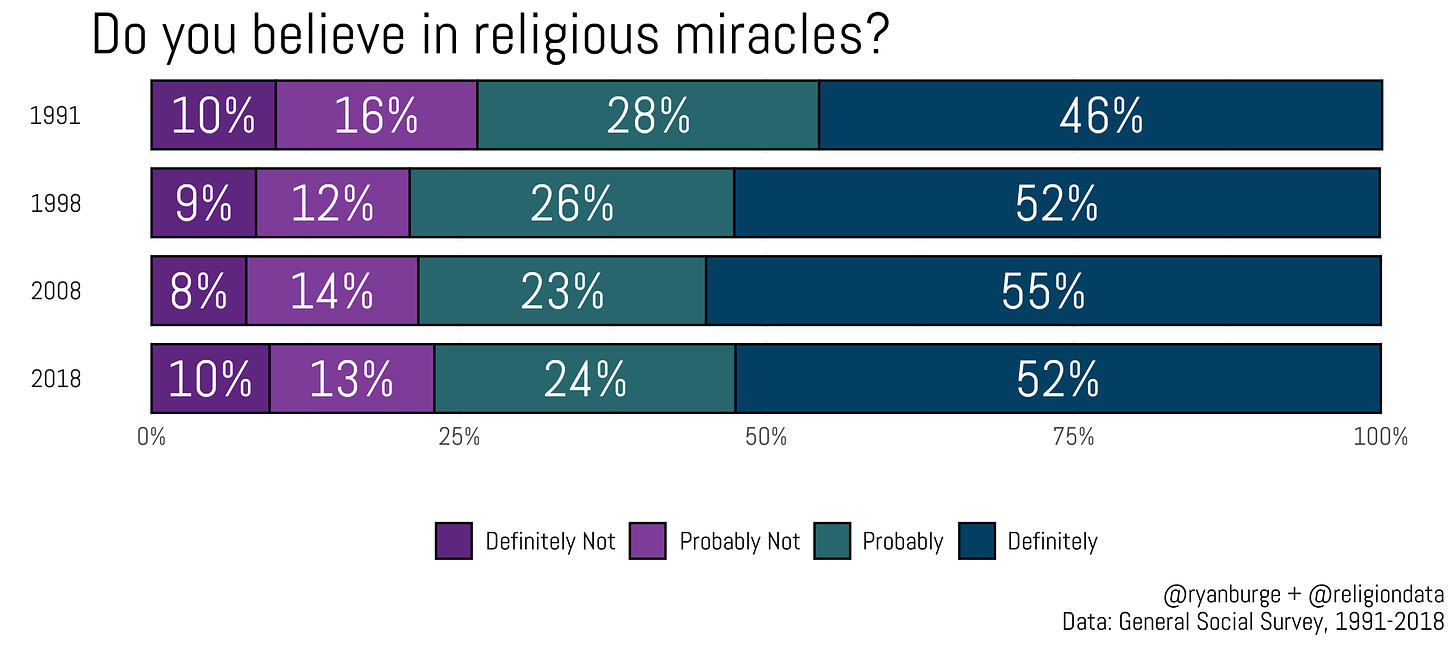

I was thinking about that story a few weeks ago after I got an email from a reader who wanted to know if I had any data about the topic of miracles. It’s a subject that I haven’t written about yet but seems like it is worthy of some analysis. When I searched the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), what I discovered was that there were a few datasets out there that did include a question about miracles. For instance, the 2007 Baylor Survey does ask folks, “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about God? God often performs miracles which defy the laws of nature”, but I was especially pleased to see that the General Social Survey has periodically asked a simple question, “Do you believe in religious miracles?” It’s only been included four times in the GSS - 1991, 1998, 2008, and finally in 2018.

In 1991, about a quarter of the sample indicated that they ‘definitely not’ or ‘probably did not’ believe in religious miracles. The plurality answer was ‘definitely yes’, though. In that sample, 46% of folks were certain that religious miracles did occur. When the question was asked again, the share who were certain of religious miracles had increased by six percentage points to 52%. Meanwhile the portion of the sample that tended to not believe dropped by about five points to just 21%.

It’s fair to say that the data collected in 1998 looks pretty similar to those last two surveys that were fielded in 2008 and 2018. In 2008, the ‘definitely’ believe in miracles percentage was the highest ever recorded at 55%. It did recede a little bit in the 2018 data, but it was still at 52%. That’s the same percentage as it was two decades earlier. In other words, the data points to the conclusion that belief in miracles had actually modestly increased between 1991 and 2018.

But anyone with a passing knowledge of American religion over the last three decades knows that the religious composition of the public has shifted. More specifically, there are a whole lot more non-religious folks in the sample in 2018 compared to 1991. In fact, about 5% of the sample were nones in 1991 compared to 23% in 2018. That may have an impact on this question because it specifically mentions “religious miracles.” Let me show you the same analysis but only include folks who align with a religious tradition.

Okay, this story is a bit different than the previous graph. The conclusion is clear - religious people are much more inclined toward religious miracles in 2018 compared to 1991. In that early survey, less than half of folks said that they definitely believed (48%). Meanwhile a quarter were in the definitely not/probably not camp. In the 2018 data, certain belief in religious miracles had climbed to 62% - an increase of fourteen points from the 1991 baseline. Meanwhile the share who chose the ‘definitely not’ or ‘probably not’ options had dropped by nearly half to just 13%.

There’s little doubt from this data that religious people are significantly more inclined to believe in divine miracles in 2018 compared to the early 1990s. But does that vary by religious tradition? Are evangelicals more open to miracles than Catholics for instance? I calculated the share of each religious group that ‘definitely’ believed in religious miracles across the four survey waves that included the question.

In 1991, belief in miracles was the highest among evangelical Protestants and Black Protestants - about three in five definitely believed. Catholics were a lot lower at 43% and the mainline was slightly below that at 35%. But you can just see the baseline increase for Christian groups between 1991 and 1998. Every single group was more inclined toward miracles in that 1998 data. For evangelicals the jump was 11 percentage points. Catholics reported the same increase in belief concerning miracles. It was even higher for mainline Protestants - increasing from 35% to 48%.

For evangelicals, a certain belief in religious miracles continued to climb through the rest of the time series. In 2008, 79% of them definitely believed in miracles and that crept up to 81% by 2018. For evangelicals, sure belief in miracles rose twenty percentage points between 1991 and 2018. For Black Protestants the increase was eighteen points, from 60% to 78%. For both Catholics and mainline Protestants, a definite belief in miracles hit its peak in the 2008 data but then receded a bit in the 2018 survey. However, each tradition has members who are more inclined toward miracles in 2018 compared to 1991.

What about other factors like education? I think it would be fair to assume that educational attainment and belief in the supernatural may run on opposite tracks. To test that I broke the sample down into four levels of education and removed the non-religious (as that would likely be a confounding variable in this analysis).

In the 1991 data, there’s a clear conclusion: those with the lowest level of education are the most likely to say that they definitely believe in religious miracles. It was 52% of folks with a high school diploma, but only 30% of people who had taken courses at the graduate level. However, something really interesting happens across the course of the survey - belief in miracles increases for every level of education.

For instance, the share of people with a college degree who definitely believe in religious miracles went from 45% in 1991 to 63% in 2018, an eighteen point jump. For people with a high school diploma the increase was much more modest, just eight percentage points. The biggest increase in a belief in miracles, though, is people who have taken graduate level courses. In 1991, just 30% definitely believed in divine intervention. In 2018, that had more than doubled to 61%. In that data, there is no statistically significant difference in the share of people who definitely believe in miracles regardless of educational attainment. That’s striking and refutes the idea that belief in the supernatural is rooted out by increased levels of educational attainment.

Let me provide one more look at this. I divided the sample into birth cohorts based on decades. I wanted to see if folks are more inclined toward miracles as they aged and if this changed among people born in the 1970s compared to those who were born in the 1940s, for instance. I didn’t exclude the nones here, either, this is the full sample.

The data points to a pretty nuanced picture regarding how belief in miracles changes across the life course. It does look like the older generations did report an increase in belief as they aged. For folks born in the 1930s, 56% had a certain belief in 1991. That increased to 66% in 2018. There was also a pretty linear increase for people born in the 1950s, too. They went from 45% with a certain belief in miracles in 1991 to 64% by 2018.

Yet the 1940s and 1960s birth cohorts don’t have that linear pattern. For each of those birth cohorts, certain belief in miracles rose between 1991 and 2008 but then it retreated just a bit in the 2018 data. I don’t know what to make of that. In the 1970s cohort, certain beliefs have continued to increase as they have moved through the life course going from 47% in 1998 to 58% in 2018. For children born in the 1980s, there’s been no change with 47% having a certain belief in 2018. Notice, though, that this cohort is clearly the least inclined toward religious miracles of any other cohort in the last wave of the GSS.

This data does generally point to some eyebrow raising conclusions. Belief in miracles is actually higher today than it was in the early 1990s. That’s true in the general population, but it’s especially the case when you exclude the non-religious. Here’s a thought about why that is - the nature of evangelicalism has changed pretty significantly. I’ve written about this before: The Future of American Christianity is Non-Denominational. Most of those growing non-denominational churches tend to be a lot more charismatic in their orientation than the largest evangelical denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention. A charismatic style in a church leads to things like hand raising in worship, possibly speaking in tongues, and at least the openness to the idea of miracles. That may be pushing belief in miracles higher among evangelicals, but that may have a spillover effect into other non-evangelical traditions, too.

Despite the rise of secularism in the United States, belief in miracles is actually increasing. That’s quite striking.

I found the end of that 60 Minutes piece about Lourdes especially poignant. Bill Whitaker writes:

It's been said about Lourdes: for those who believe, no explanation is necessary. For those who do not, no explanation is possible.

Code for this post can be found here.

I have two personal miracle stories. Neither involves healing or suddenly getting money to pay a bill.

In 2010-ish I was powerful in the Spirit, more so than now. I was a faculty member at a big private university. We had a faculty room with a refrigerator, sink, and our big 4 foot tall master copy machine. I was running VERY late to give a class a test. Kids DO NOT like it when you don't give them tests when they are scheduled, as they want to "cram and forget." I had the master copy in my hand and on my way to class ran to the copy room. There were at least two other people (maybe three). I have eyewitnesses. The copier was dead. I don't mean, lit up and not copying, but dead as if it had no power.. Lights were off. No one could get it to work. I had NO TIME for this and I jammed my test in the slot and laid hands on the copier and shouted "IN THE NAME OF JESUS, WORK!" and it shot to life, copied all my tests. The minute I pulled them out of the hopper, it died and no one else could get it on.

The second was I was with my brother-in-law at a gas station. My wife and I had a practice of whenever walking about just staying alert to what we called "favor of the Lord," pennies, nickels, whatever, which we put in a jar and haven't touched to this day. (One time I found $14 outside Taco Bell---but that's not the miracle). This day, as I always did when gas was automatically pumping, I walked around the pumps just checking for favor of the Lord. Nothing. I "heard" a strong stirring. "Go around again." So obediently I walked around the pump again, looking studiously. Nothing. I got this a second time: "Go around again." Now I'm thinking this is some trick or I'm on a camera or something. But I went around a third time and right in my pay, where I couldn't have missed it even if I wasn't looking, was the brightest, shiniest penny I had ever seen. You could have seen it from two pumps away. I said, "Good one, Lord."

Ryan, I wonder if there is a factor in the age cohorts that would see in a very general sense children of the 30's are in the cohort of the 50's and children of the 40's are in the cohort of the 60's and if this relates to the parallelism of the two sets of cohorts? And does that apply elsewhere: as in church attendance or tithing, etc.? I appreciate all the hard work you do Ryan.