Can We Predict a Christian Conversion?

Or is it just something that defies explanation?

There’s this huge disconnect between what religious people want and what social science can provide. It’s one of the biggest frustrations of the type of work I do. I get asked hundreds of questions a year that I totally understand the motivation behind - but I know that there’s just no way in the world to accurately answer such a query using anything resembling rigorous social science methods. I think there are two primary reasons for this.

The things that academics are concerned with are not at all the same as what folks in the pews are thinking about on a daily basis. This a pervasive problem in the Ivory Tower - no points are deducted for being incredibly disconnected from actual problems in the real world. In some ways, I think the opposite is true - being highly specialized, technical and esoteric denotes a type of sophistication that is rewarded. I could talk for hours about the number of papers I’ve seen that use incredibly technical and fascinating methods to answer the most pedestrian questions. When I used to go to academic conferences, I would constantly mutter under my breath, “Yeah, but who really cares about this?”

The other problem that occurs is that the average person has no concept of what kinds of questions are even answerable based on the type of data that we have access to at this present moment. I often get an email, a DM or a Twitter reply that asks an incredibly interesting question to me. The problem is that to answer that question, I would need a budget of several million dollars and a couple years of my life to answer. It’s just a truism in this work - we gravitate toward topics that are easier to assess with the data constraints that we have.

Evangelicals, understandably so, are very interested in the idea of true religious conversion. They want to see people jump from the realm of the non-religious into a Christian tradition where they are deeply rooted. How often does this happen? And, is there any way at all that I can shed some light on factors that make someone more likely to have a Christian conversion experience?

I have data that can generally get us in that direction. It’s called the Cooperative Election Study’s Recontact Survey. They asked 60,000 people a bunch of questions in 2020 and then followed up two years later by recontacting 11,000 of them and asking them the same questions again. It’s called a panel survey, for what it’s worth. It allows me to get closer to answering that pesky question about Christian conversion.

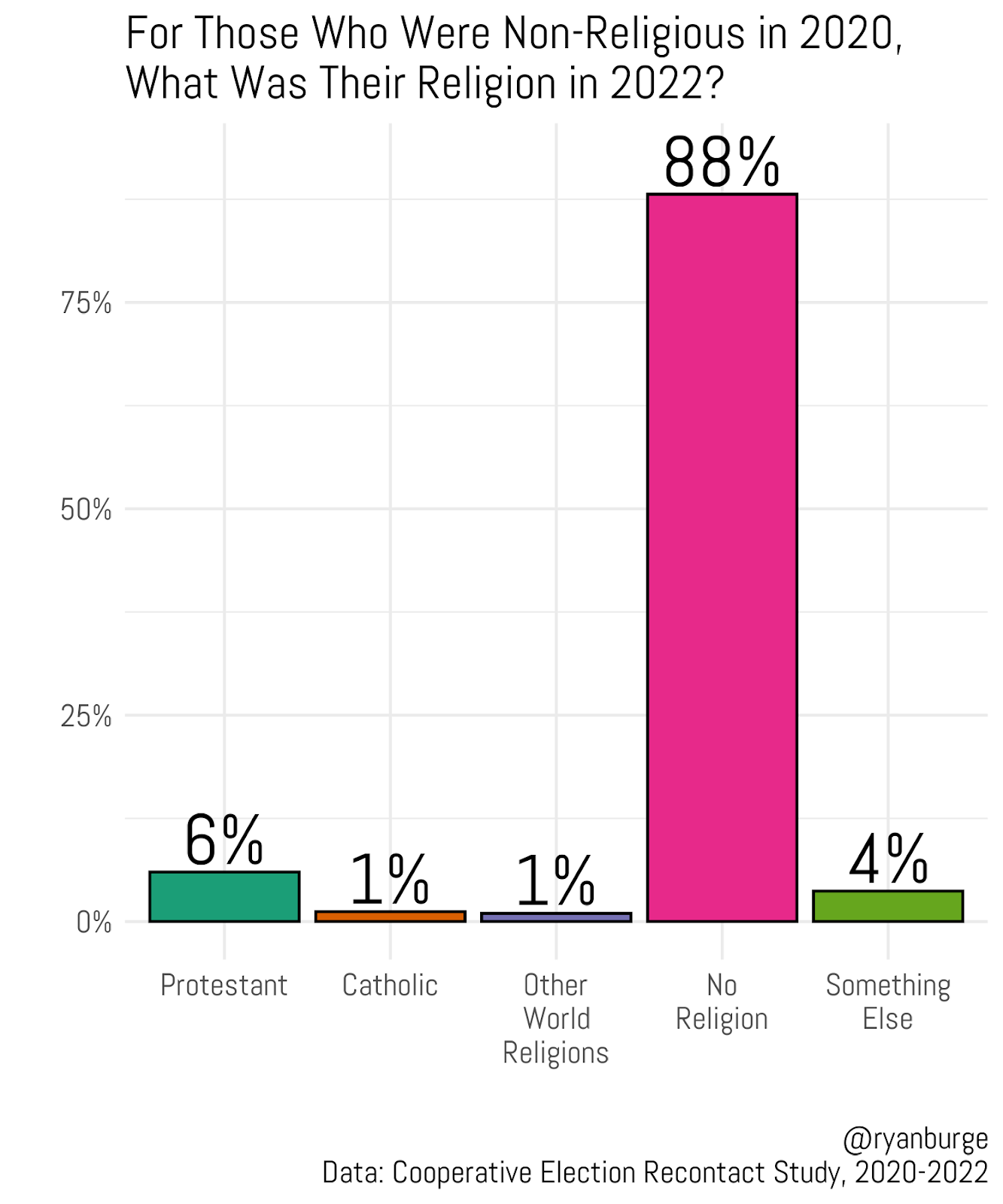

For those who identified as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular in 2020 - where were they on that same religious question in 2022? Here’s what that looks like.

The answer is that the vast, vast majority are still non-religious - about 90% of nones are still nones when asked again. Said simply - most people don’t change their answer two years later. But for the 12% who did actually switch, where do they end up? The most likely landing spot is Protestant Christianity at 6%. Then, another 4% fall into the black hole of the “something else” category. That’s basically where they check the “other” option and get a free response box to fill out. Those people are a methodological nightmare.

So, we’ve got about 6% who become Protestants and another 1% who become Catholic. So, that’s seven percent of nones who are now Christians when asked about their religion two years later. Let me put some real numbers on this.

We started with 11,009 people. Of that, 3953 were non-religious in the 2020 survey. Of that, how many switched to a Christian faith - a total of 285. So, we started with over 11,000 and now we are down to less than 300 people. We have just excluded 97.5% of my entire sample. And, for the record, a panel survey of 11,000 is absolutely huge to begin with. It would have been completely unheard of 20 years ago. Do you see the issue that’s arising here? I can only slice this data so thin before it just completely falls apart.

Speaking of slicing it again - of those folks who went from non-religious to Christian (and yes I’m including Catholic here so I can have a reasonable sample size), what is their church attendance after they make the switch?