Are Americans Especially Distrustful of Religion?

Or are they just cynical about every institution?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

A few years ago I was talking to an editor of a major newspaper who had to make some tough decisions about what topics his reporters would cover and what stories would make the front page. He noted, like almost everyone in the media business does, that clicks and traffic matter now more than ever. For those who haven’t been paying attention to the economics of journalism - let’s just say that the future is pretty bleak. Which means that there’s an incentive among editors to focus on stories that they know will get some traction.

He was fully aware that stories with scandal, violence, and corruption get a lot more clicks than a feel good story about a family reuniting with their long lost pet. He mentioned a term to me that I have been thinking about a lot - “negativity bias.” It’s the idea that negative stories draw more eyeballs than positive ones. In the journal Nature last year a research team published an article with a simple title, Negativity Drives Online News Consumption. The upshot was simple, “For a headline of average length, each additional negative word increased the click-through rate by 2.3%.”

One very real implication of this is that trust in American institutions has eroded significantly over the last several decades. The General Social Survey has asked respondents how much confidence they have in over a dozen institutions - things like major companies, the federal government, and the scientific community. But given the name of this newsletter, I bet you can guess which institution I want to focus on today: organized religion.

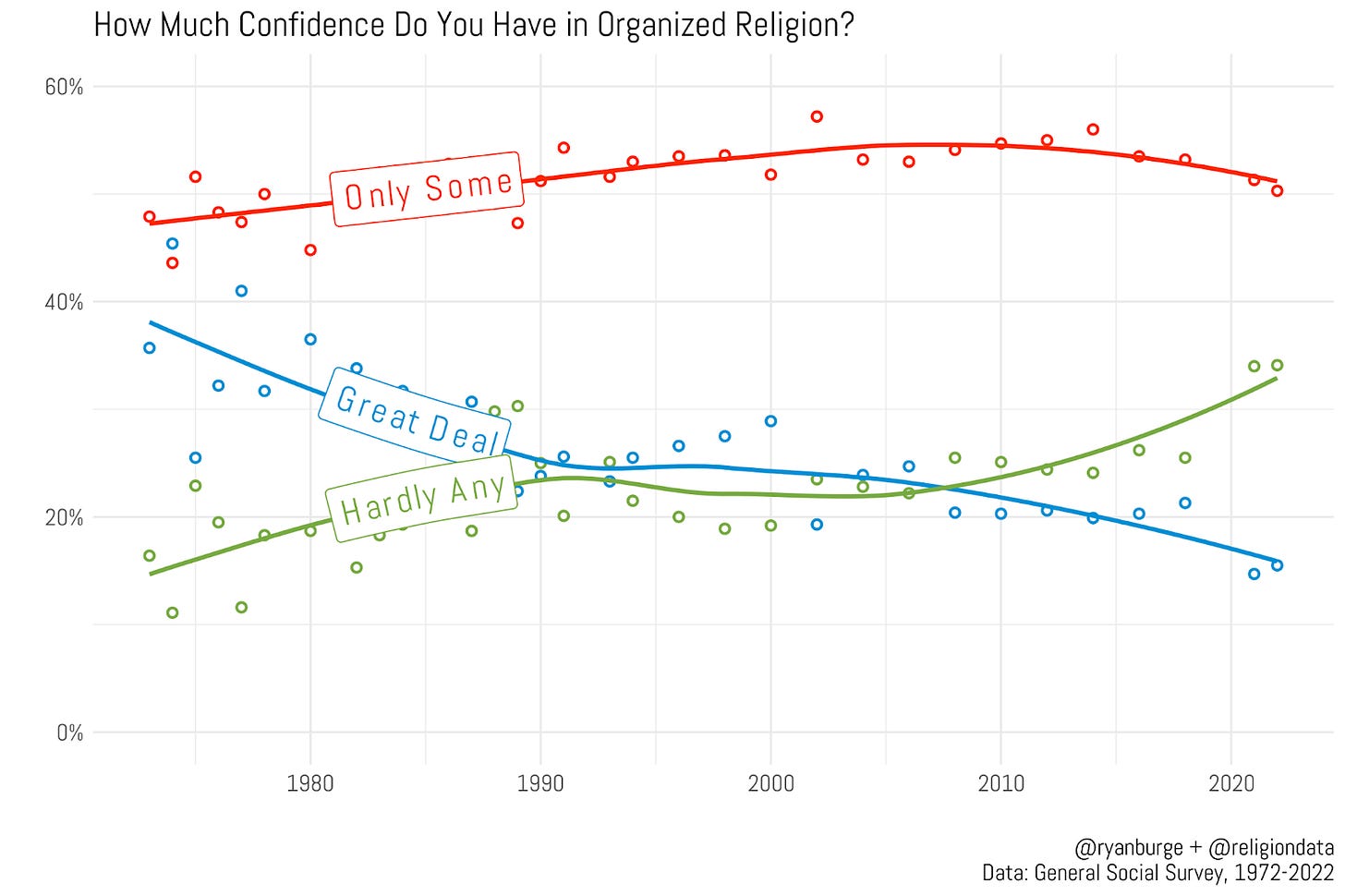

Respondents were given three options - they had a great deal of confidence in organized religion, only some confidence, or hardly any confidence. Here’s how those percentages have shifted over the last five decades.

The most popular response option from the very beginning has been the middle one - only some trust in organized religion. It was about 48% of the sample in 1972, but that share has slowly crept up in the intervening decades. In the late 2000s, it was at an all-time high of 55%. But it’s receded just a bit from there and it currently sits right around 50%.

However, the share of folks who said that they had a great deal of trust in organized religion has really taken a dive. Between 1972 and 1990, that share dropped from about 38% to just about 25%. It stayed at that level for about fifteen years, then began to slide again. In the most recent data, about 15% of folks expressed a great deal of confidence in religion, while the share who had hardly any trust has risen from 15% in 1972 to 35% today. It’s fair to say that the average American is significantly more skeptical of religion today than a person from fifty years ago.

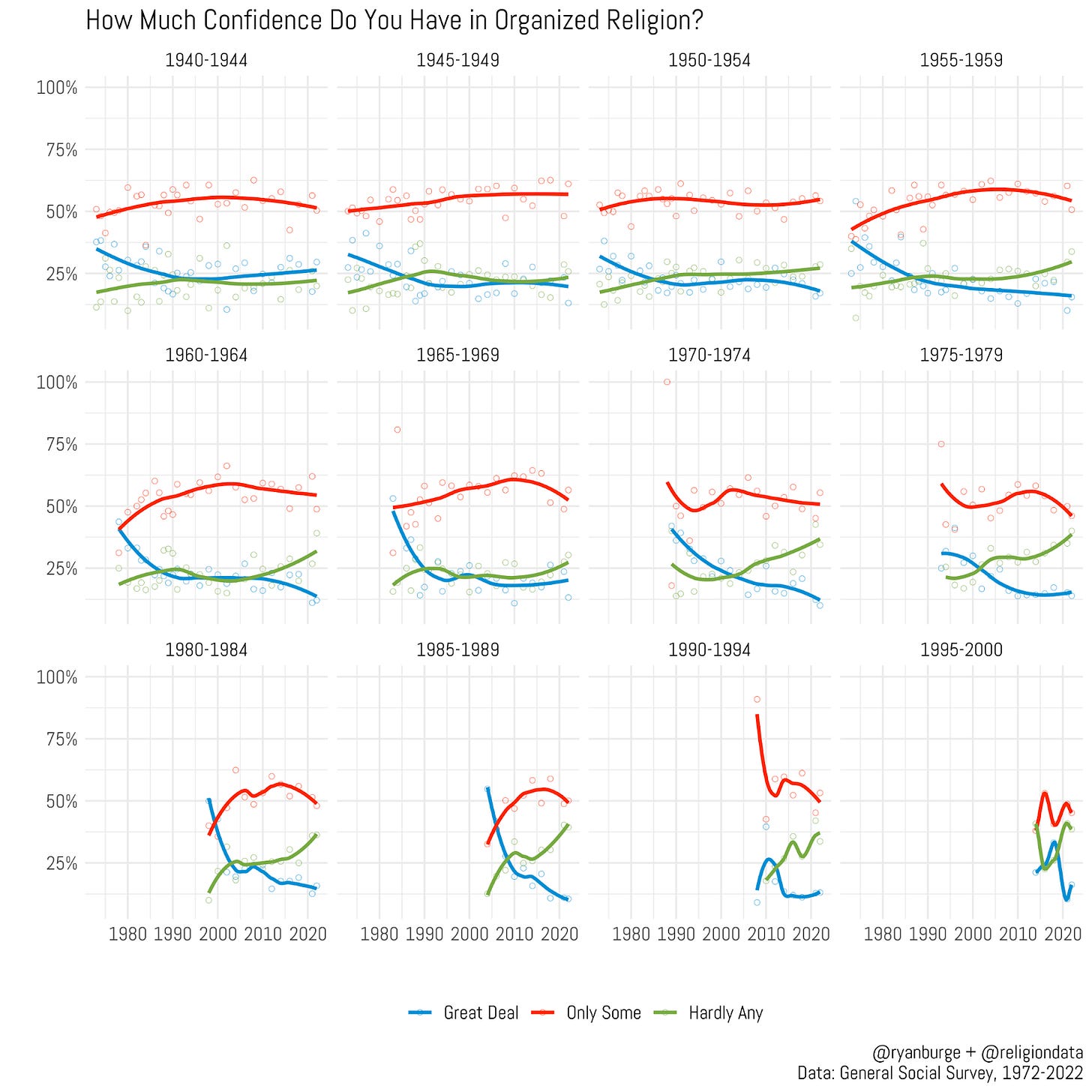

But what’s driving that change? Is it the fact that people are just growing more skeptical as they age or is it really generational replacement where older, more trusting people are dying off and are being replaced by young adults that are much more cynical?

If you look at the top row of birth cohorts, you can see a pretty clear pattern in the blue line (that’s folks saying that they have a great deal of trust in religion). Among people born in the 1940s and 1950s, trust dropped clearly between 1972 and about 1990 and it edged down very slowly from that point. But you can also see some of that same pattern in people born in the 1960s, too.

For those born in 1970 or later, the pattern of a quick drop then a long plateau is just not as clear. Instead, it’s just a continued decline as these cohorts age. That’s really clear for folks born between 1970 and 1974 - the share with a great deal of trust has dropped by half as they have aged. From this angle it looks like both theories are true - each cohort became less trusting as they aged but also younger cohorts were less trusting than older ones. In other words, trust in religion has eroded across all age groups.

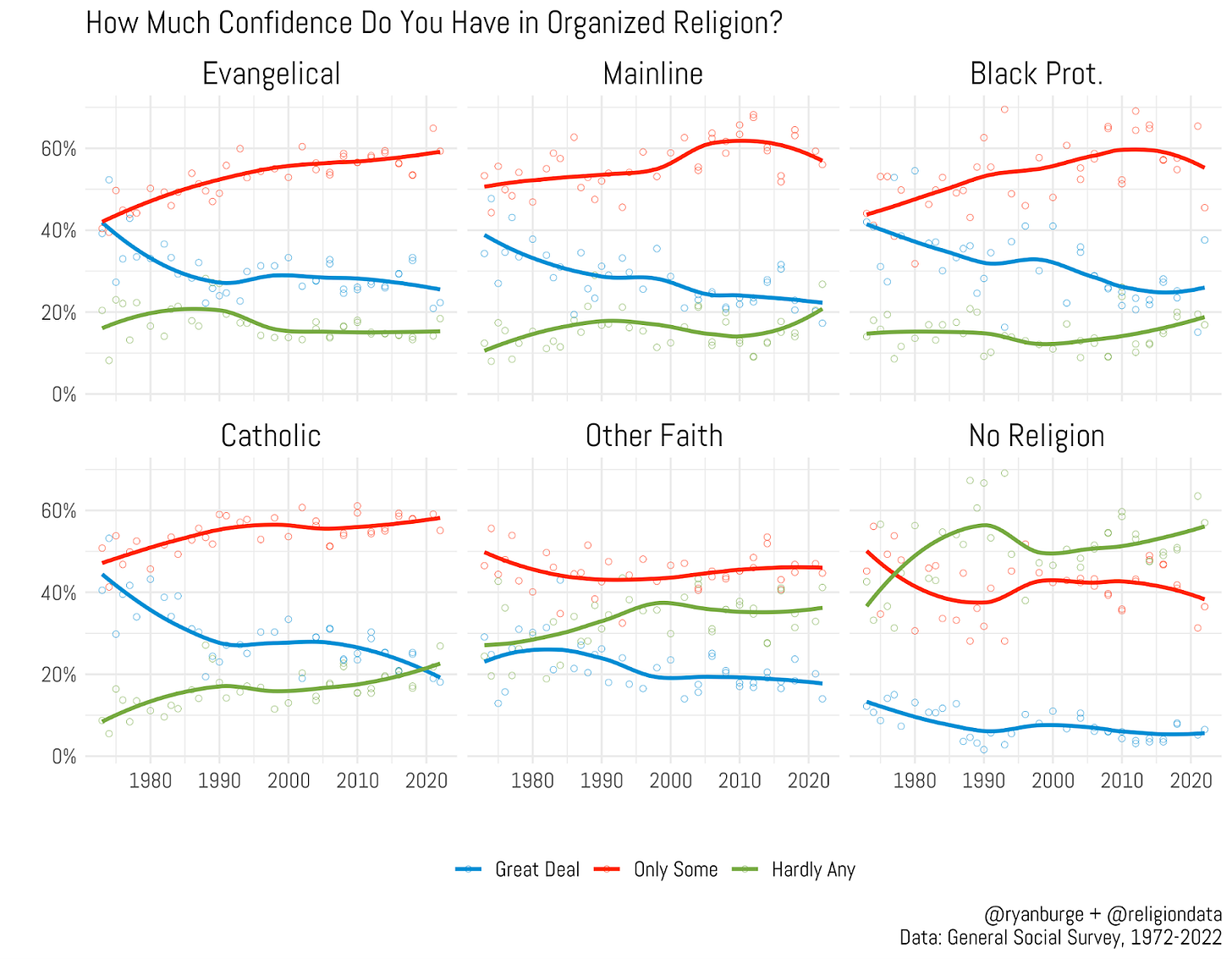

But maybe there’s a really simple reason for this - older people tend to be more religious and younger people are more likely to identify as religiously unaffiliated. It logically follows that non-religious folks would have less trust in religion. So, let’s see if trust in organized religion has declined even among Christians.

Well, this is a pretty striking graph. Trust in religion has dropped even for many religious people! For instance, about 40% of evangelicals had a great deal of trust in 1972, that’s dropped by nearly half over the last fifty years. You can also see that with mainline Protestants, Black Protestants, and Catholics, too. There’s a striking reality when looking at Catholics in the sample, they are the only group that currently is more likely to say that they have “hardly any” trust in organized religion than to say that they have a “great “deal” of trust.

But what about the non-religious? You can see that trust in religion has never been that robust. In the early years of the survey, nearly half of the nones said that they had at “only some” trust in organized religion. By the early 1980s, the most popular response option was undoubtedly “hardly any” trust. What I wanted to point out is the fact that this line has continued to rise over time. In fact there’s been very little deviation in the trend lines over the last 20 years or so.

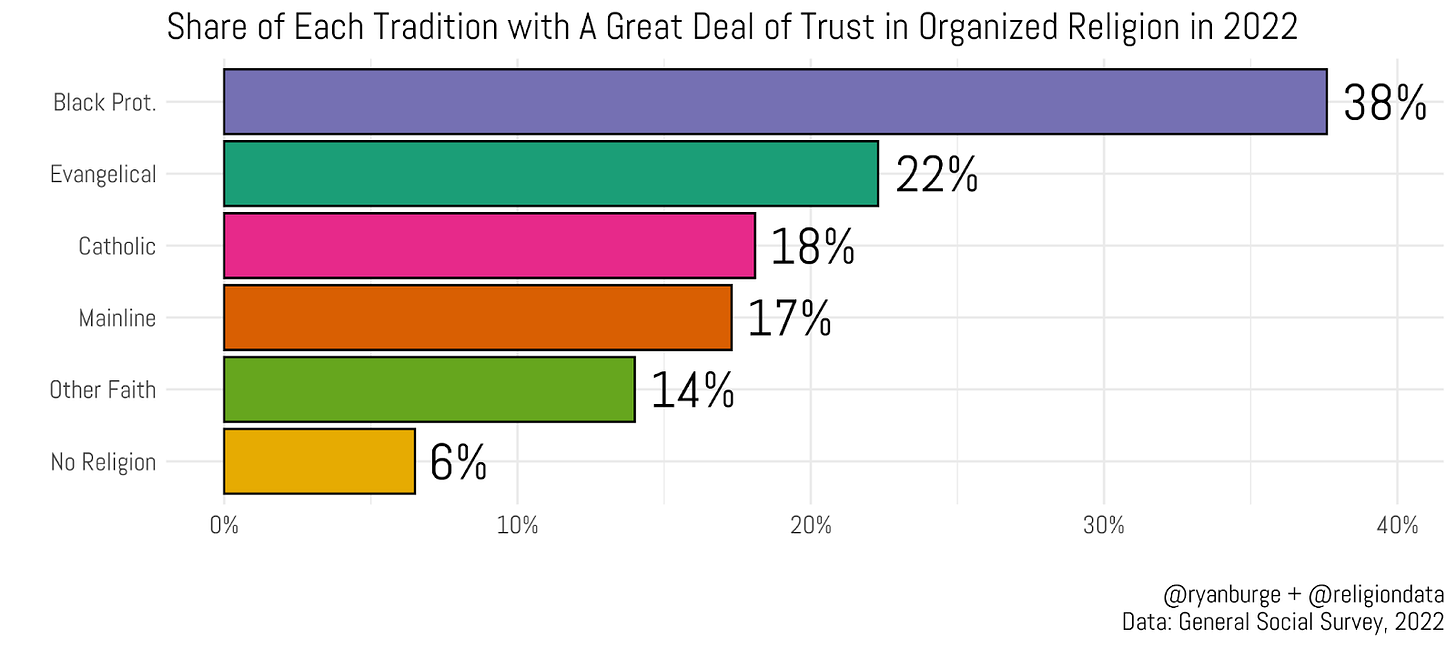

Below is the share of each religious tradition that said that they had “a great deal of trust” in organized religion in the most recent data collected in 2022. It makes plain how trust in organized religion is incredibly low.

The group that clearly stands out here is Black Protestants - with nearly four in ten saying they had a lot of faith in religion. They are really an outlier here. Among evangelicals, mainline Protestants, and Catholics, the share who have a lot of trust in organized religion is less than 20%. About 80% of evangelicals are part of an organized religious group that they don’t trust very much. It’s quite overwhelming to think about, really.

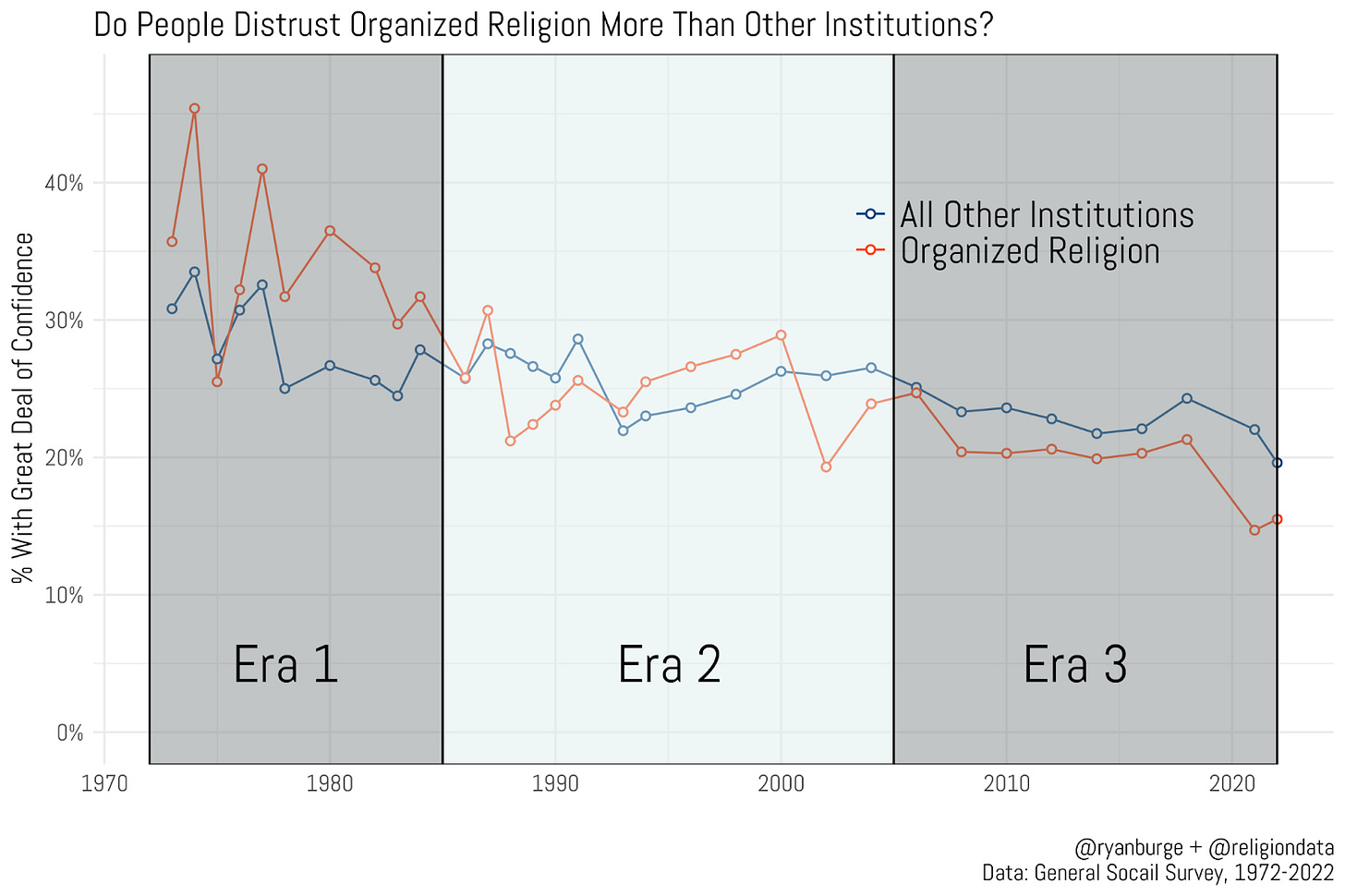

When I was creating these graphs, I had a question lingering in the back of my mind - are Americans especially distrustful of religion or is it the case that religion is being caught up in the larger way of distrust that is sweeping over the United States in the last five decades?

The GSS has been asking about confidence in a bunch of institutions for decades (unions, the media, banks, the Supreme Court). So I calculated the share of the sample who reported a great deal of confidence in those other institutions and created an average trust score. Then I did the same for the question about organized religion. This is the end result of that calculation.

I think I can probably divide this graph up into three fairly distinct eras of institutional trust.

Era 1: Between 1972 and the mid-1980s, I think it’s fair to say that people seemed to trust religion slightly more than they trusted other American institutions. The gap isn’t huge here - probably averaging between three and five percentage points. But I think it’s fair to say that religion had a slight edge.

Era 2: Between the mid-1980s and the mid-2000s, the lines basically ran in parallel. It’s evident from this angle that religion was not trusted more or less than other institutions like labor unions or the media. The public didn’t really seem to distinguish between the two.

Era 3: The mid-2000s to today. It appears that religion has fallen below the trend line for other institutions. In fact, there’s only one survey year between 2002 and 2022 where the point estimates overlap each other and that happened in 2006. It looks like religion is ranked about two to three points lower than the rest of the institutions in American society.

I think about this issue a lot. There’s no doubt in my mind that the average American is much more anti-institutional today than the average American from the 1970s. A growing chorus of people are convinced that the structures that built the United States like religion, science, the media, and the government are corrupt, abusive, and deserve little respect. I don’t know if this trend toward distrust will continue into the future. What I do know is a world without institutions is not something that the average American has ever really considered. The old saying, “you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone” seems pretty appropriate in this situation.

Code for this post can be found here.

Hi, this is well written and I found the drop offs in hi-trust in religion by age cohort to be interesting, thanks for compiling the data. But the institutions you're referring to at the end aren’t the ones that built America; they’re relatively new constructs, mostly centralized and consolidated within the past fifty years. Many of the key institutions that did build America, such as genuinely decentralized and publicly accessible mass-member parties, robust state and city governments with real power, and a scientific ecosystem that was diffuse, experimental, and independent before World War II, among others, either no longer exist or have been transformed beyond recognition. What you’re observing isn’t just a generic loss of faith in “institutions” but a recognition that what replaced the old structures is fundamentally different in nature, worse in performance, and corrupt to its core. The centralized exclusionary membership parties that masquerade as political representation today were never part of the original design; the current form of "science" as a bureaucratic and industrialized apparatus really only took shape in the late 1970s, and state and city governments have been rendered largely ineffectual, unable to act as real counterweights to the national center. The growing distrust isn’t a rejection of institutions in general, it’s a rejection of the new centralized order, which has proven itself corrupt, unaccountable, and incapable of producing the broad-based prosperity and participatory governance that once existed. The real tragedy is that most people don’t realize just how much was lost in the process.

Religion becoming less trusted than other institutions strikes me as support for Aaron Renn's Negative World thesis.

Though I can't help but notice that among evangelicals, trust seems to be flat-to-positive since 1990 or so. The "Great Deal" line is flattish while the "Some" line has increased mostly at the expense of "Hardly Any".