Why Religion, Not Income, Predicts the American Vote

Inside the data that shows socioeconomic status barely matters once you know someone’s religious tradition.

Here’s one advantage of being a professor that I’ve only really started to appreciate in the last couple of years: if you sit with an idea long enough—thinking about it repeatedly for days on end—you eventually find a new way to approach a problem. There’s nothing magical about it. It’s more like a brute-force method of discovery. You just keep turning an idea over until something clicks and a new angle emerges.

When I talk to my students about this process, I compare it to yanking a jagged, ugly rock out of the ground. It’s dusty, uneven, and honestly not very impressive. But over time, your thinking wears down those rough edges. You polish that rock simply by handling it—turning it over in your mind again and again over the course of months or years. And eventually, if you stick with it, you end up with something more valuable than any gemstone: a clearer idea of how the world actually works.

Teaching helps accelerate that polishing process. Explaining the same concepts every semester forces me to refine how I think and talk about them. That happened again last fall while I was teaching Religion and Politics at WashU. We were covering Jewish Americans—their basic demographics, where they tend to live, and how they vote. One of the first things you notice when you look at the data is how consistently Jewish Americans appear near the top of the socioeconomic hierarchy. On both education and income, they rank among the highest of any religious group in the country.

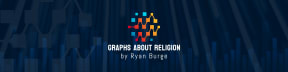

The scatterplot below makes that obvious: educational attainment on the x-axis, mean household income on the y-axis. Jewish groups cluster right up in the top-right corner.

I know there are a lot of groups displayed here, but I actually left many out by limiting the analysis to traditions with at least 250 respondents in the sample. Even with that threshold, the first thing that jumps out is how strong the correlation is between income and education for virtually every group.

The idea that a college degree is no longer financially worthwhile has risen exponentially in the general public, but the empirical record remains remarkably consistent: people with a bachelor’s degree earn substantially more over their lifetimes than those without one.

But once you look more closely, some religious patterns emerge that are worth pointing out. A number of Pentecostal traditions cluster in the bottom-left corner of the plot—groups like the Assemblies of God and the Pentecostal Church of God. Moving toward the middle, you find a wide mix of traditions: atheists, Latter-day Saints, Muslims, and a variety of Protestant denominations, all occupying similar socioeconomic territory despite very different theological profiles.

The top-left portion of the graph contains just three major groups: Hindus, Jews, and mainline Protestants. Hindus report the highest income of any tradition—around $85,000 per year—while three branches of Judaism (Reform, Conservative, and “Other Jew”) all average above $80,000. Episcopalians and members of the PCUSA also land in this high-income, high-education quadrant, both averaging above $75,000.

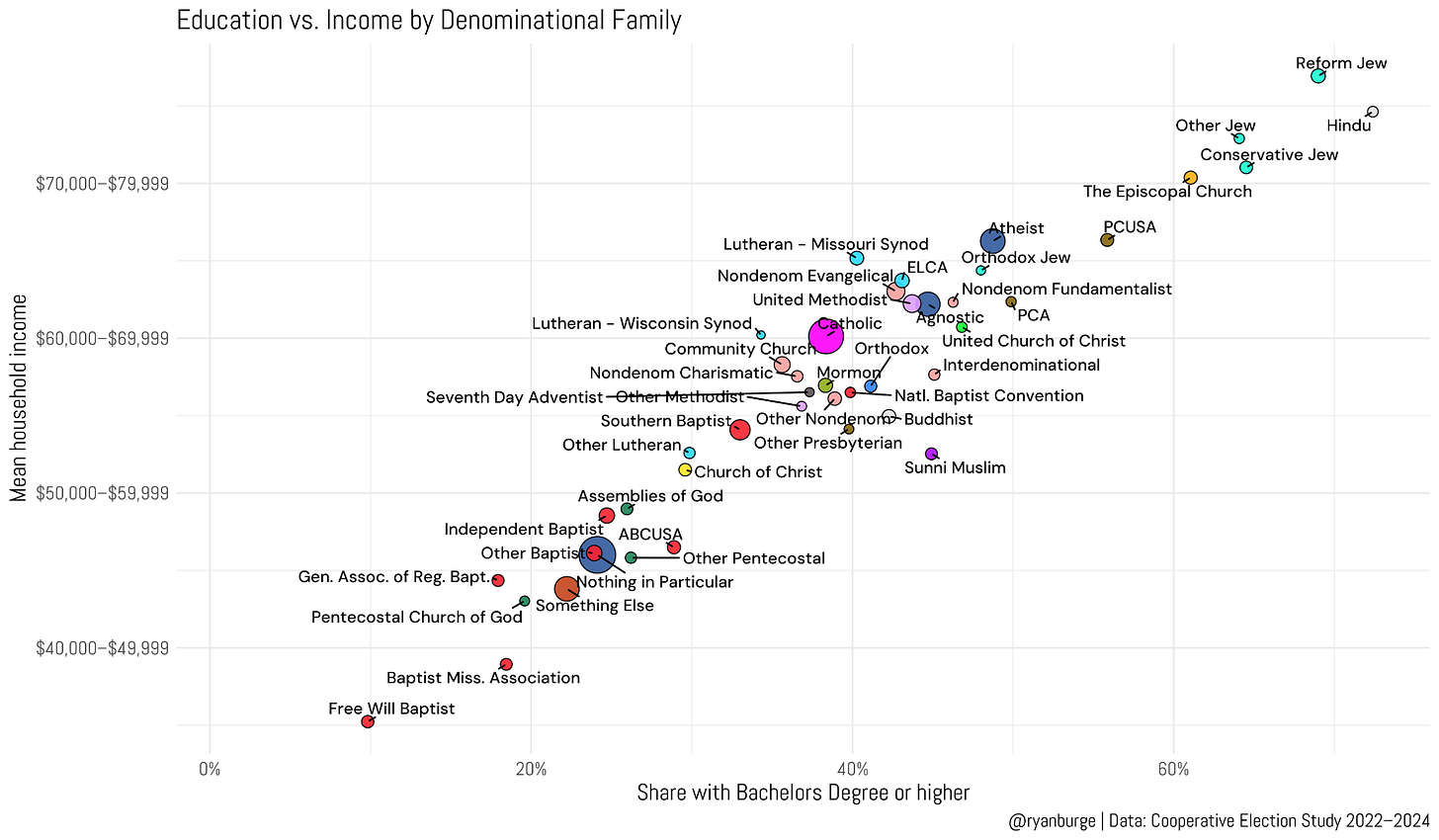

As a visualization, that scatterplot is deeply satisfying because these two variables—education and income—track together so cleanly across almost every group. But now let’s take one variable from that analysis (income) and replace educational attainment with something very different: the share of each tradition that identifies as Republican. That graph is below.

Yeah, good luck finding any kind of discernible trend line in this data. It practically looks like I fed a random-number generator into the Republican-percentage column—the points are scattered everywhere. (By the way: the small differences in mean income between the two scatterplots are simply because each graph keeps only respondents who answered both relevant questions.)

Take Reform Jews, for example. They sit way up in the top-left corner—meaning they have some of the highest incomes of any group in the dataset, but fewer than 20% identify as Republicans. Atheists and agnostics live in a similar neighborhood: high income, but overwhelmingly Democratic. Hindus remain near the top, though they shift slightly toward the center because about a quarter of them identify with the GOP.

And then there’s… the right-hand side of the plot. I’m not even sure “cluster” is the right term—it’s more like a theological traffic jam. Most of the Protestant traditions pile up there, with median incomes in the $50–$60K range but wildly different partisan profiles. That actually creates some fascinating contrasts. Members of the United Church of Christ, for instance, have almost the exact same average income as people who identify as non-denominational. Yet the partisan breakdown could not be more different: about 29% of UCC respondents are Republicans, compared to nearly three-quarters of non-denominationals.

Looking at that scatter of points, a conclusion starts to bubble up: income, at least on its own, just isn’t a very strong predictor of partisanship. But I wanted to push on that idea a bit harder by looking within a handful of the largest religious traditions in the Cooperative Election Study.

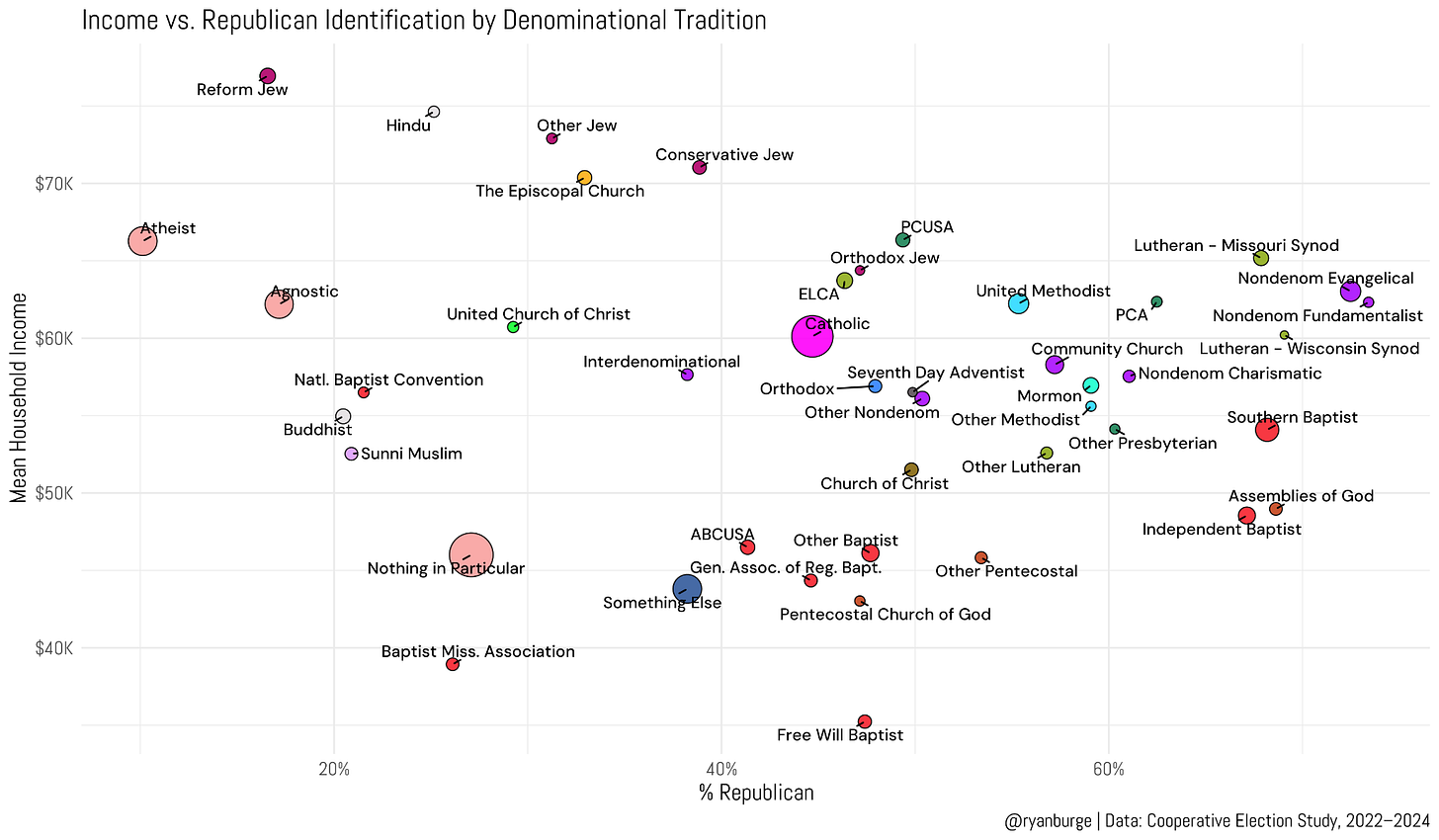

This is a graph where I need to pause and remind you to pay attention to the confidence intervals. Once you slice any religious group into four income buckets, the sample sizes get smaller, and that naturally widens the margin of error. But even with that caution in mind, the overall pattern is striking: for nearly every group in this analysis, there’s no meaningful relationship between reported household income and a Trump vote in 2024.

Take Southern Baptists. Among those making under $40,000 a year, about two-thirds voted for Donald Trump. Among those earning between $80,000 and $120,000, that number rises to about 78%. That roughly ten-point increase is statistically significant—but it’s also the exception, not the rule.

Look at other large traditions. Among United Methodists, there is essentially no difference in Republican support between someone earning $35K a year and someone earning $115K. The same flat pattern shows up among non-denominational Protestants, white Catholics, Jews, Buddhists—you can go group by group and see the same story repeat. Within a religious tradition, income just doesn’t seem to move the needle very much.

Where the action is—where the real differences show up—is across traditions, not within them. A Southern Baptist and an atheist with the exact same income are separated by sixty percentage points in their likelihood of voting Republican. That gap utterly dwarfs the tiny within-group differences by income.

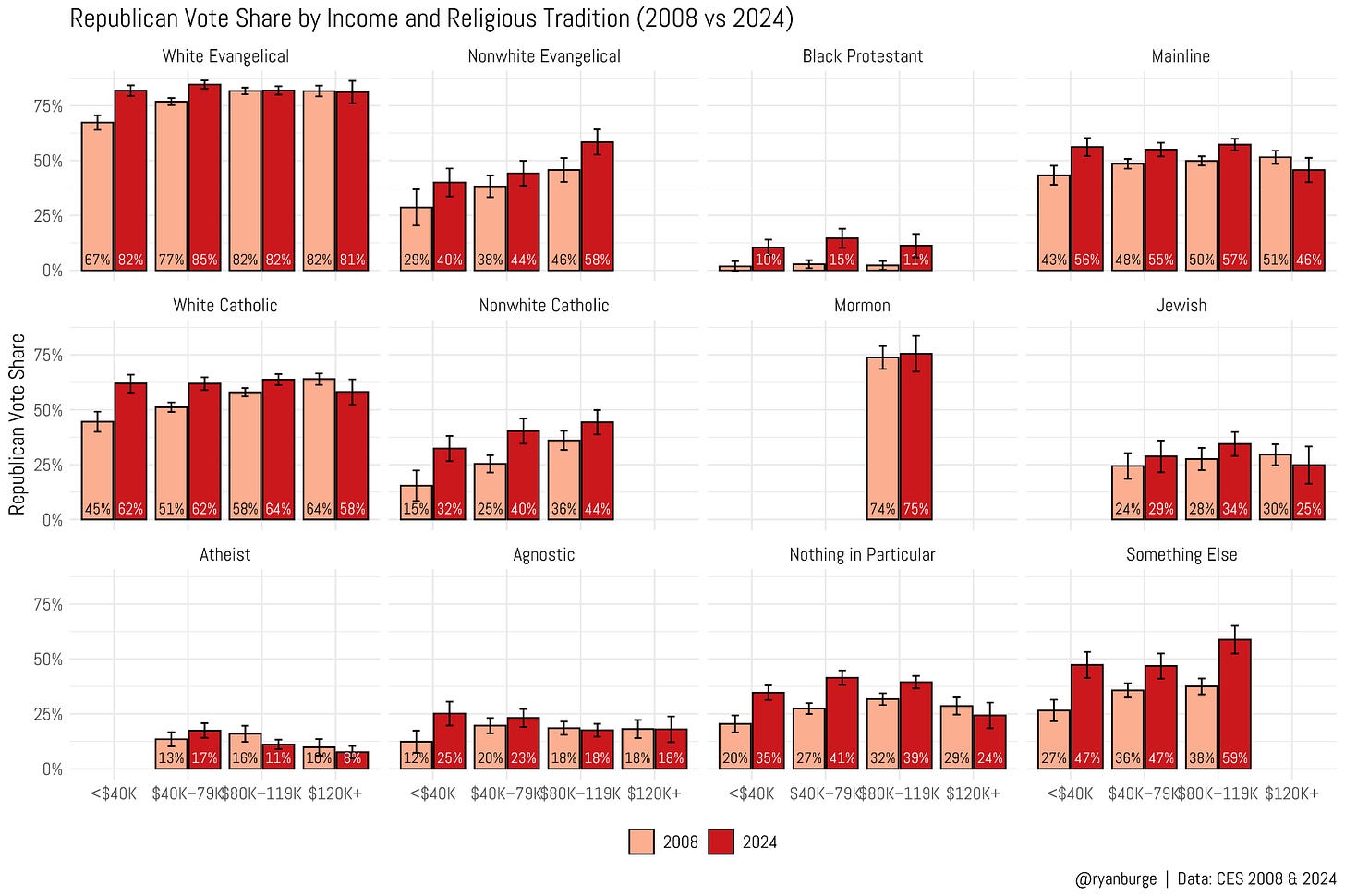

And guess what? This pattern isn’t unique to the 2024 election. It also shows up when we rewind the tape back to 2008. For this comparison, I only included matched pairs—subgroups that had enough respondents in both datasets to make a reasonable comparison. That’s why several cells are blank: small sample sizes simply don’t allow for reliable estimates.

But when you do have enough data to compare across time, the story is familiar. Among white evangelicals, for instance, Trump performed a bit better than McCain among people in the bottom two income buckets, but support among higher-income white evangelicals was virtually unchanged. The GOP’s strength among wealthier evangelicals has been remarkably stable for at least fifteen years.

A similar pattern pops up in several other traditions. Among white Catholics, Republican gains among lower-income respondents are noticeable. You see the same thing among mainline Protestants. But once you look at the higher end of the income scale, the differences between 2008 and 2024 shrink dramatically. In most groups, vote choice among higher earners barely budged.

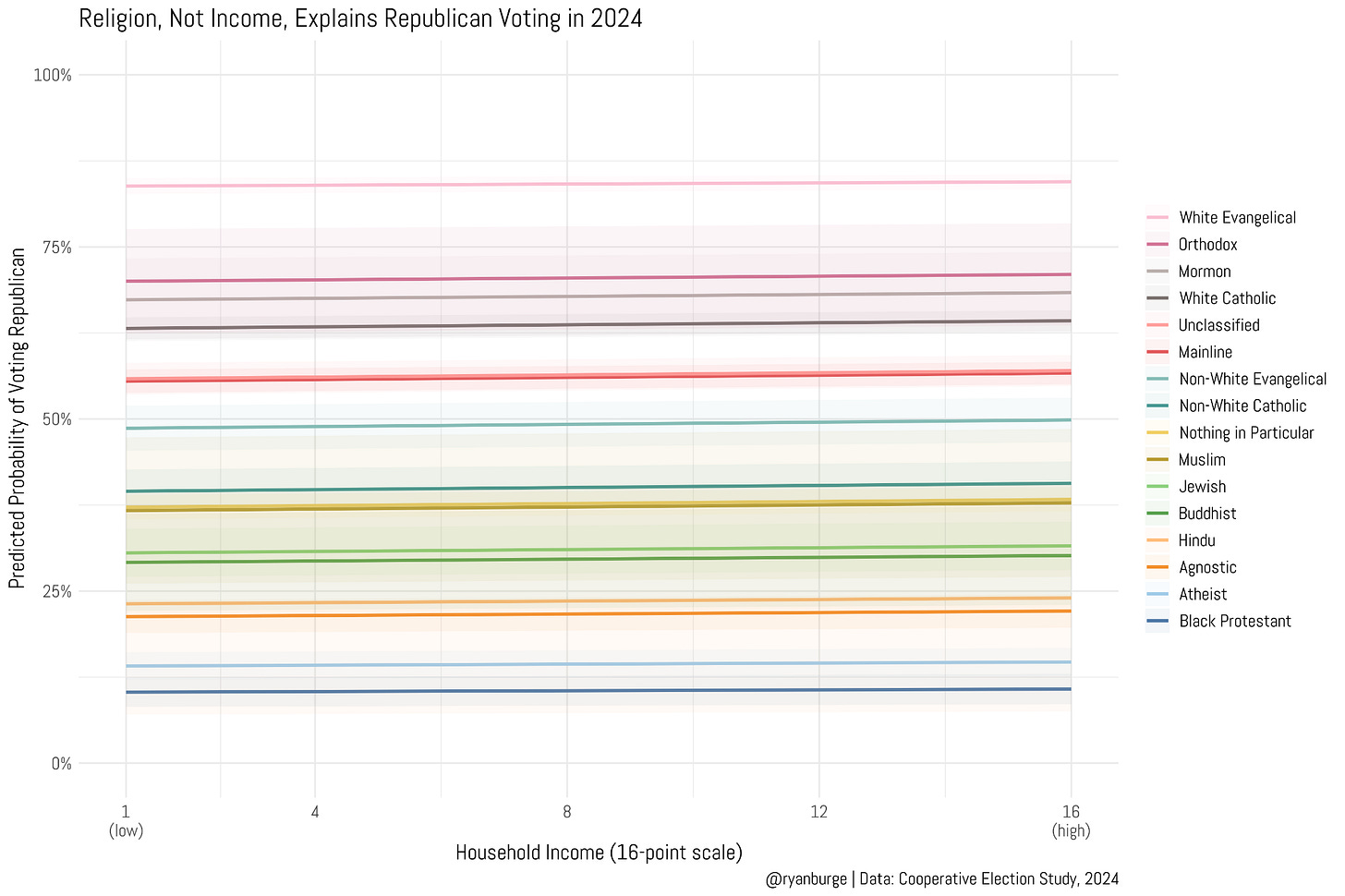

At this point, the conclusion becomes hard to avoid: income is not doing much work here. So I wanted to push that intuition one step further and run a simple regression. Nothing fancy—just a straightforward attempt to predict whether someone voted for Trump in 2024 using income and a set of sixteen major religious traditions.

Let’s just say the resulting visualization is not exactly a thriller.

At first I thought I should just facet this graph and create sixteen separate panels—one for each tradition—but then it hit me: doing so would actually bury the point I’m trying to make. So instead I threw them all into a single graph.

And look at what happens. Those lines are about as flat as lines can be. Once you control for religious tradition, the effect of income on a Trump vote drops to essentially zero. If you stare at the graph long enough you might convince yourself you see a slight upward or downward tilt across the income scale, but that’s just trying to squeeze meaning out of noise.

But the real punch of this visualization isn’t the flatness—it’s the spread. Putting all sixteen traditions on the same axes makes the story unmistakable. White evangelicals sit at the very top of the chart (insert shocked-face emoji), while Black Protestants are parked all the way at the bottom. Trump pulled support from over 80% of white evangelicals and under 10% of Black Protestants—even when comparing respondents with the same household income.

In other words: income barely budges the needle within traditions, but traditions themselves are separated by enormous political gaps.

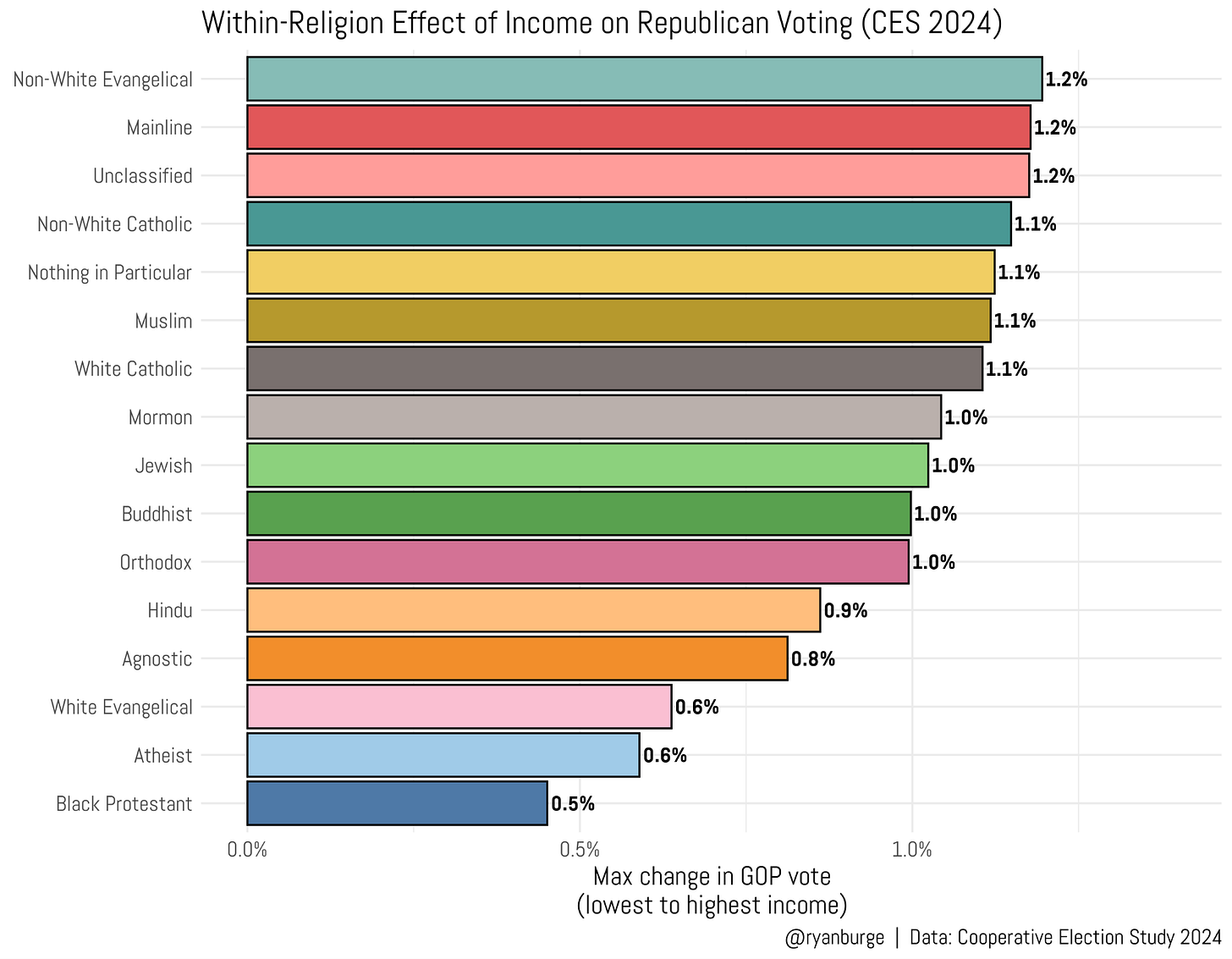

It may be even easier to see this when we compare how much those predicted probabilities actually change from the very bottom of the income distribution to the very top.

Yeah, I think this graph does an excellent job of conveying just how little income matters on Election Day once you control for religious tradition. Among non-white evangelicals who make at least $500K per year, they are only 1.2 percentage points more likely to vote for Donald Trump than members of the same group making less than $10K per year. And that’s actually the largest gap I found.

For Latter-day Saints, the difference between the highest earners and the lowest is one percentage point. For white evangelicals, it’s 0.6%. For Black Protestants, just 0.5%. I’m not even going to bring up statistical significance here, because the substantive story is the real key: income simply has no meaningful impact on vote choice within these religious traditions.

This brings me back to that conversation in my Religion and Politics class at WashU. One of the questions on the final exam was:

There appears to be a disconnect between the socioeconomic demographics of Jewish Americans and their voting behavior. Based on demographics alone, how ‘should’ they vote? And how do you explain how they actually vote?

The point I wanted them to articulate is that demographic factors do matter—but they can be completely overshadowed by other forces. Jewish Americans are white, well-educated, and high-income. On paper, that’s a textbook profile for a Republican voter. Yet about two-thirds consistently vote for Democrats.

And now I can show exactly why.

If we take the average Jewish household income and plug it into a model predicting Republican voting, we get a predicted probability of about 32%.

But if we change just one thing—not the income, not the education, not the race—just flip the religious identity from “Jewish” to “White Evangelical”—that predicted probability jumps to 85%.

In other words:

The difference isn’t income.

It’s religion.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

This seems to make sense. I assume this is why we see some groups vote against their own self interest, because it's needed to stay in their group. For example, low income evangelicals fighting against the ACA even though they are a primary beneficiary of it.

One of the downsides of democratization is that every election becomes apocalyptic. Each faith tradition responds accordingly to whichever evil they understand is their duty to ward off. This notably was not the attitude of Jesus, who approached government as something like a necessary evil to be endured rather than agent of social transformation or perpetuator of injustice.