Who Believes in the Prosperity Gospel?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

If someone asks me who the most famous preacher in the United States is, the answer is honestly quite simple. It’s Joel Osteen, by a mile. He leads Lakewood Church in Houston, Texas. His congregation meets in what used to be the home of the Houston Rockets basketball team. Its seating capacity is nearly 17,000. Osteen’s first book Your Best Life Now sold a reported eight million copies.

But, what really propels Osteen into a different level of fame is his presence on television. According to data from 2007, the church spent about $30 million to buy thirty minute blocks of TV time in hundreds of media markets across the United States. The end result of this expense is that, according to their own records, about seven million people watch Osteen’s sermon each week. He has ten million followers on Twitter.

However, one criticism that other Christian leaders tend to levy against Osteen is that he preaches a form of the prosperity gospel. He has intimated that true followers of Jesus Christ will find a prosperous life full of health, healing, and financial gains while on Earth. He said last month that he was “not a poverty minister.”

This piece by Tara Isabella Burton does a nice job of explaining the contours of prosperity theology and some of its most high profile proponents (Osteen included). But, one has to wonder - how pervasive is this understanding of the Gospel among average Americans?

Back in 2012, the General Social Survey included a special module of questions that is housed by the Association of Religion Data Archives that specifically focused on issues related to views of the Bible and theology. There are two questions that tap into some of the basic tenets of prosperity theology.

To what extent did you read the Bible to learn about attaining wealth or prosperity?

To what extent did you read the Bible to learn about attaining health or healing?

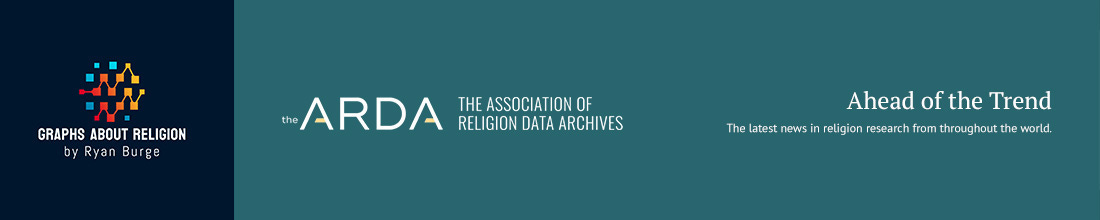

Here’s the distribution of those answers in the entire sample who said that they primarily read the Bible as their sacred text.

It’s fairly evident from this data that prosperity theology is not pervasive across the American public. In fact, 45% of respondents say that they never read the Bible to learn about attaining health or healing and 63% have never looked to the scriptures to learn about how to obtain wealth or prosperity. In contrast, just 15% of folks said that they often looked to the Bible for guidance on healing and 11% sought out biblical texts to learn about gaining wealth.

However, there are niches inside American Christianity in which the prosperity gospel seems to be more pervasive than others. For instance, I can think of no high profile mainline Protestant pastor who is an advocate of prosperity theology. And, in many corners of American evangelicalism there is a tremendous amount of disdain for this type of theology. I am thinking specifically about denominations and traditions that tend to be more reformed in their theological outlook.

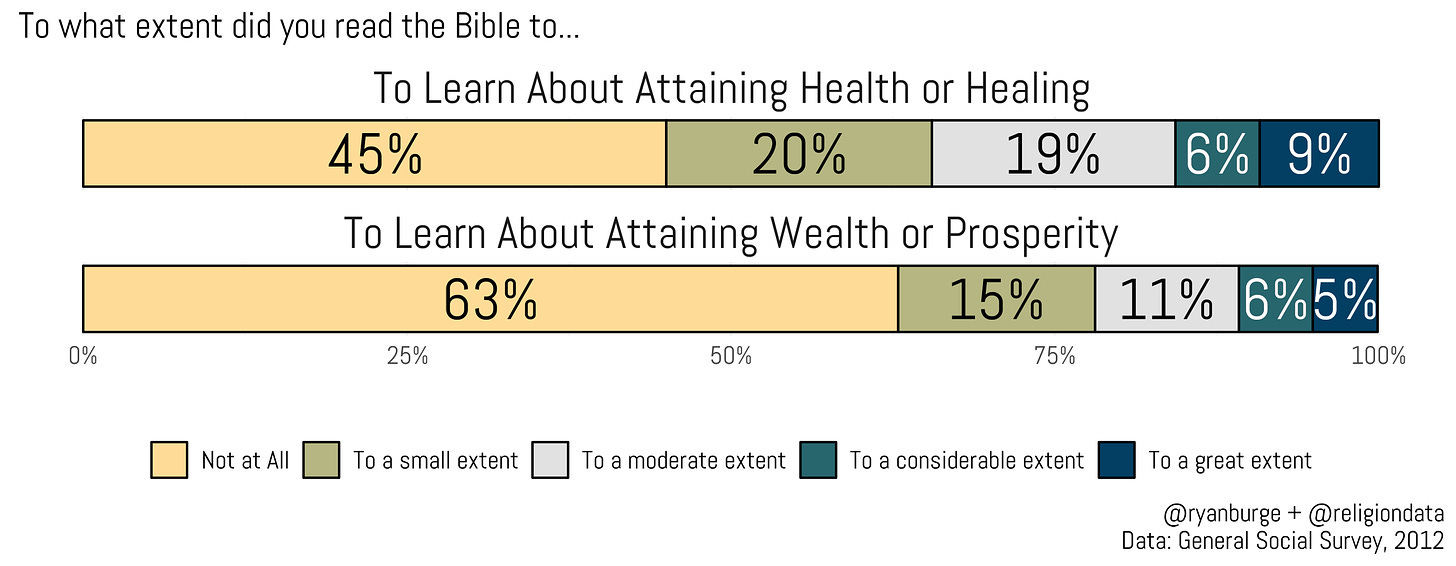

If I were asked to pinpoint the types of churches that tend to be more apt to embrace a version of the prosperity gospel, I would point to traditions that are closer to the charismatic or Pentecostal movement. Pastors like Jesse Duplantis, Kenneth Copeland, and Creflo Dollar are ones that come to mind when I think of prosperity theology. Their audiences tend to be much more multiracial than other flavors of evangelical Christianity. I wondered if there was any evidence in the data that these prosperity views were more widespread among Christians of color.

And, the data here is as clear as it could be. Non-white respondents are more likely to embrace certain aspects of the prosperity gospel–as measured by these two questions in the General Social Survey–compared to white Christians. While over half of white Christians say that they never consult the Bible for information about healing/health and 72% never read the scriptures for help in obtaining wealth, those shares were just 24% and 40% of non-white Christians respectively.

Just six percent of white Christians chose one of the top two options when it comes to learning about prosperity from the Bible, it was 24% of non-white Christians. There’s just no escaping this conclusion - reading the Bible to learn about attaining health, healing, wealth, or prosperity is more pervasive among American Christians of color. It could be that the different historical experiences of non-white American Christians has encouraged them to come to the Bible with different questions and expectations around health, healing, wealth, and prosperity compared to white American Christians.

Unfortunately, the sample is not large enough to dig into specific racial groups (Black, Hispanic, Asian, etc.). There is ample evidence in the scholarly literature that the Black Church has a much stronger strain of prosperity theology than white Christian traditions - Kate Bowler’s book Blessed is an accessible entry point to this larger literature.

But race may not be the only factor that is strongly associated with this type of theology. Recall earlier that prosperity preachers often encourage their flocks by telling them that God will reward their faithfulness and generosity. For some, this could seem like a pathway for them to climb up the rungs of the economic ladder and move into the middle or upper middle class. Obviously, many critics of the prosperity gospel point to examples of preachers in this movement taking advantage of those who are struggling to make ends meet.

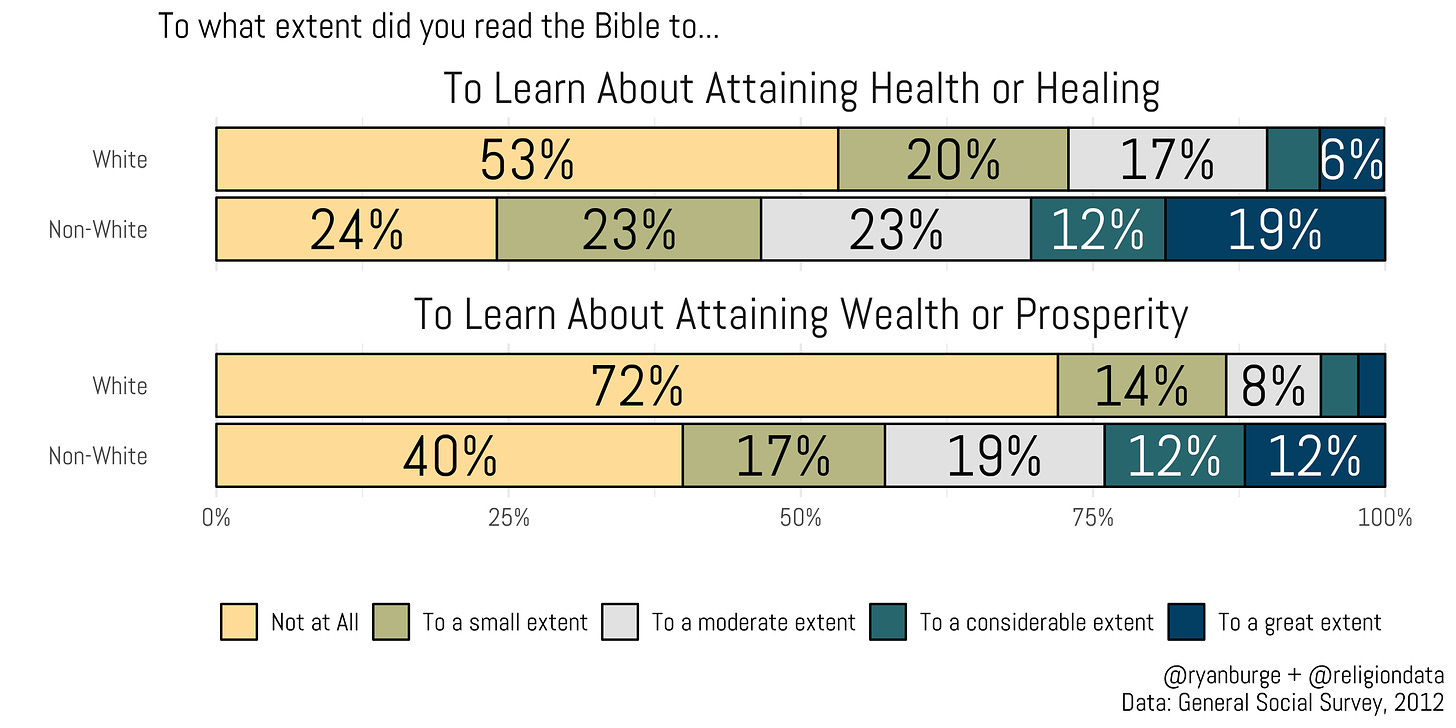

I broke the sample into a number of income brackets and then calculated the share who said that they read the Bible at least “to a small extent” to understand things like health/healing or wealth/prosperity. The results are striking - Americans at the lower end of the income distribution are much more likely to look toward the scriptures as a way to find a pathway toward prosperity. Among those making less than $40,000 a year as a household, about two-thirds said that they looked to the Bible for advice about health and healing and a bare majority said the same for wealth and prosperity.

As one moves up the graph and looks at those reporting a higher level of household income, a belief in the prosperity gospel begins to wane. For instance, among those making at least $75,000 per year, just 22% say that they have used the Bible as a guidebook on financial success. It is important to point out there is a drop off in regards to the question about health and healing from the bottom end of the economic spectrum to the top, but it’s much smaller than the measure that focuses specifically on money.

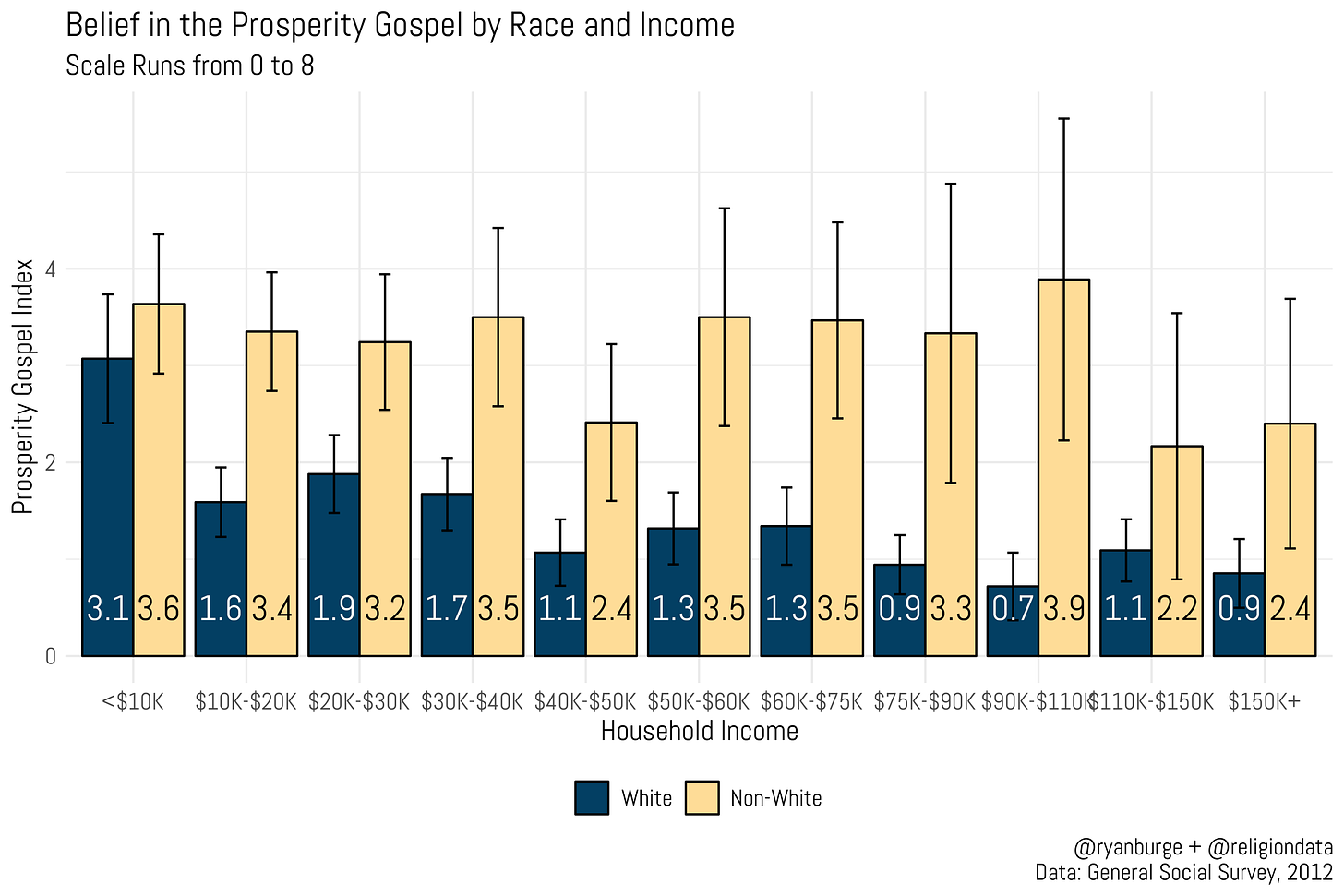

So, let’s combine the last two variables - race and income and see how they impact the embrace of prosperity theology. To simplify this I created a scale of both questions. I coded the “not at all responses” as zeroes and the “to a great extent” responses as fours and added both questions together to get an index that runs from 0 (meaning total rejection of PG) to 8 (complete embrace of PG). Then I calculated the mean score across income levels and racial groups. Here’s what I get.

Okay, the empirical portrait is coming into sharper focus now. There are clear gaps in the prosperity gospel metric for white and non-white respondents, once you control for household income. For instance, look at those making between $30K and $40K per year. Among white respondents, the average score was 1.7 - for non-white respondents it was double that rate (3.5). This gap stays large through the income spectrum. In fact, in many income brackets the non-white mean score is triple that of white respondents who make the same level of income.

The other thing I want to point out is that there’s an unmistakable trend line for white respondents - as income increases, the mean prosperity gospel score goes down. For those white respondents making between $10K and $40K, the mean hovers around 1.75. But it’s about half that rate when you looking at those making $75K or more. Among non-white respondents, there’s really no drop off between the lowest income bracket and those making $100K per year.

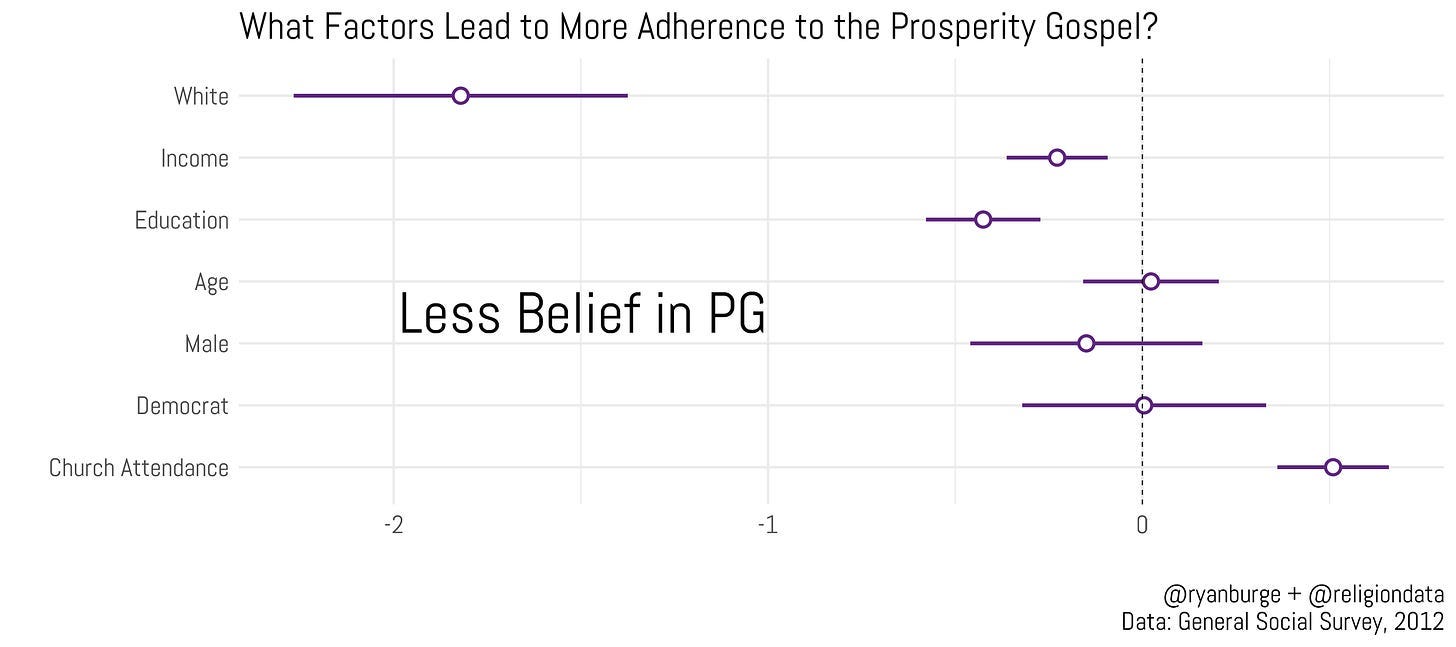

But let’s end this with a more rigorous test - a regression analysis. The thing we are trying to predict here is the mean prosperity gospel score (using the same measure I described above). I included variables for race, income, education, age, gender, partisanship and church attendance. If the coefficient is positive, that means a higher score on the PG scale. A negative score indicates a lower PG score. If the point estimate (or the error bar) intersects with zero, there’s no statistically significant relationship.

We have a total of one variable that predicts a higher likelihood of embracing the prosperity gospel and that’s church attendance. All else equal, someone who attends church with a higher frequency reports a higher PG score.

There are three variables that are not statistically significant: age, gender, and partisanship. In each case, we can’t say with any degree of certainty if those variables drive up (or down) the PG score.

There are three variables that predict a lower likelihood. Both income and education drive down a belief in the prosperity gospel. The coefficient for each is statistically the same, meaning one is not more predictive than the other. Generally speaking, those with more incomes and higher levels of education are less likely to be proponents of PG.

The last variable is the one at the top of the plot - race. All other factors being held equal, a white respondent’s score on the PG scale is nearly two points lower than their non-white counterparts. It’s easily the most predictive factor in this analysis.

There’s doesn’t seem to be any indication that prosperity theology will recede in the future. In fact, it may have gotten a significant boost in the last several years with the presidency of Donald Trump. Trump was a member of Norman Vincent Peale’s church in New York City. Peale is most famous for his book The Power of Positive Thinking, which is often seen as one of earliest modern articulations of the prosperity gospel. Trump also surrounded himself with a number of ministers who have strong ties to the prosperity gospel movement like Paula White.

Even when this political moment passes, there’s no reason to believe that prosperity theology will fade in any way. Russ Douthat once said, “The prosperity gospel, in its various forms, has always been with us and always will.” It clearly plays a small but influential role in American Christianity in the 21st century.

Code for this post can be found here.

The two questions really don't belong together. Health is an intrinsic part of the New Testament message. Lots of miraculous healings for blind men, lepers, and dead men. Wealth is NOT in the gospels at all. Exactly the opposite.

Wealth was invented by the medieval popes as a way of justifying their own wealth and avarice. They said Jesus was rich just like the popes, who inherited his wealth by apostolic succession. The Inquisition started when some heretics tried to point out that the real Jesus was poor and fiercely anti-wealth.

Good discussion. Rings true to my experience, and it's sometimes an uncomfortable fact to note that blacks are heavily overrepresented in Prosperity Gospel (but I think as a group it's still majority white), even after adjusting for income. The connection to poverty also rings very true.

I have a very poor and somewhat troubled (white) relative who actually lives very close to your neck of the woods, Ryan. And he was telling me about how he needs to use all his money to buy gold, based on his read of one verse or another of the Bible, and then he'll finally be a rich man. It's at least better than Powerball tickets or sending his money to a televangelist, so I wasn't sure how much I should try to dissuade him.

One thing that marks Osteen is that he himself is rich and uses his wealth to engage in conspicuous consumption. You can likely judge someone's attachment to the Prosperity Gospel largely by how he feels about that fact. To a full-throated Prosperity Gospeler, the normative reaction is something like, "That could be me!"

Of course, some people go the other way and say a pastor should be poor. I am fine with my pastor -- who has 8 kids and pastors to a middle-class audience -- being middle-class. We pay him enough to provide for that family at a mid-middle-class lifestyle. But I would have a big problem with him being wealthy and using his wealth as Osteen uses his.

The Douthat quote is a good one. There's something universal about the human drive to pray to God or the gods or the spirits for wealth and prosperity. So it has a tendency to show up in every religious tradition, including Douthat's own Roman Catholicism, but most often at a poorer and less educated/catechized "folk" level.

If the Reformed tradition is better about this, as Ryan points out, it's that, for one, to adhere strictly to the Reformed tradition isn't very "folk". You could say Pentecostalism is derived, ultimately, primarily from the Reformed branch of Protestantism (which is to say, not Lutheran, Anglican, or Anabaptist) and is one way it can turn out when that branch goes "folk".

But two, Calvin himself described self-denial as "the sum of the Christian life." Everything about the Reformed ethos militates against excessive material comfort and conspicuous consumption.