Those Non-Denoms are Just Southern Baptists, Right?

How Non-Denominational Christians Compare to America’s Largest Christian Traditions

It’s become my hobby horse at this point—non-denominational Protestant Christianity. I swear, it’s somehow gotten more legs than the “nones” in the larger cultural discussion about religion. Whenever I do any kind of analysis of denominational statistics, there’s always a chorus in the feedback: what about those non-denoms? It’s like folks can’t get enough of this new phenomenon. For those of you who want a longer-form essay from me that contains no charts or graphs, I’d point you to The Demons of Non-Denoms, which I published in Asterisk Magazine a couple of months ago.

But this is my Substack, after all—and it’s called Graphs about Religion—so I’m going to try to trace the contours of non-denoms across a few arenas that I’ve really examined a lot over the years: racial composition, a bit of age analysis, and then a deeper dive into the religious views and attendance patterns of non-denoms compared to other Protestant groups.

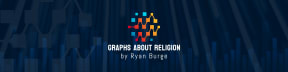

However, I have to start at the very top level and show you the latest General Social Survey data on the rise of the non-denoms. The GSS has been asking about religious affiliation from the very beginning of the survey, way back in 1972. It’s really the only dataset that exists that can track this phenomenon across a five-decade time horizon.

For followers of this newsletter, you’ve seen this graph before—but without the 2024 data included. The share of all Protestants who were non-denominational was just 5% in 1972. It was little more than a rounding error in the grand sweep of Protestantism. Today, about 30% of Protestants are non-denoms. But that number has been really unstable over the last four survey cycles.

It was 23% in 2018, then jumped a full ten points in the 2021 survey to 33%. It ticked up again to 34.7% in 2022. The most recent estimate dropped a full six percentage points to 28.7%. That’s just a very noisy metric. I’m not fully convinced that the 2022 number wasn’t a bit too high—or that the most recent figure isn’t a bit too low. I still think the statement “about 30% of Protestants are non-denoms” is empirically defensible.

In terms of all Americans who are non-denoms, the figure was just 3% back in the early 1970s. Today, it’s somewhere between 12–14% of the population. In real numbers, that translates to roughly 45 million non-denoms in the United States. For comparison, the Southern Baptist Convention has about 12.5 million members, and the Catholic Church has about 62 million.

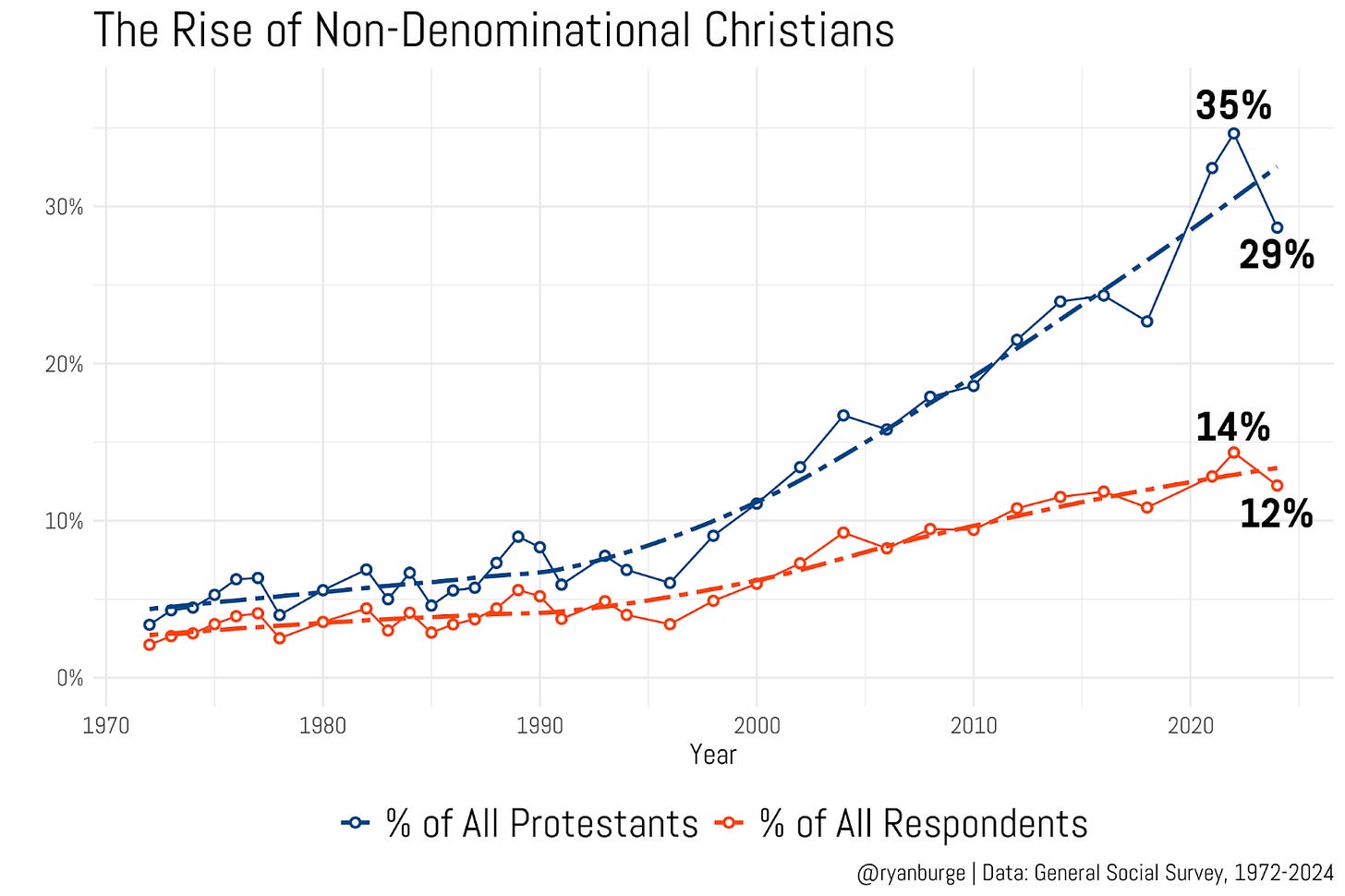

And not only are there a lot of non-denominational Christians in the United States—their future looks quite bright in the data. One reason is straightforward: their overall age profile is significantly younger than many of the largest Protestant denominations. To show this, I visualized the age distribution of a dozen groups using a beeswarm plot. This gives a clear sense of how age is distributed within each tradition. I also added the mean age of each denomination at the top of each swarm.

Again, followers of this newsletter shouldn’t be surprised by the groups listed up top. Among the six oldest traditions, four come from mainline Protestant Christianity: the United Methodist Church (mean age of 60.3 years), the Episcopal Church (60.2), the Presbyterian Church (USA) (59.2), and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (58.7). They’re joined by two evangelical groups as well—the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and the Southern Baptist Convention.

The groups across the bottom are the youngest, and on this metric, non-denoms actually do pretty well. Their average age is 52.6. That’s only about four years older than the mean age of the entire sample. You can also see in their distribution that there are plenty of younger non-denoms. They do have a fairly strong concentration around the Baby Boomer ages, but many of those will be replaced by younger folks taking their place over the next couple of decades.

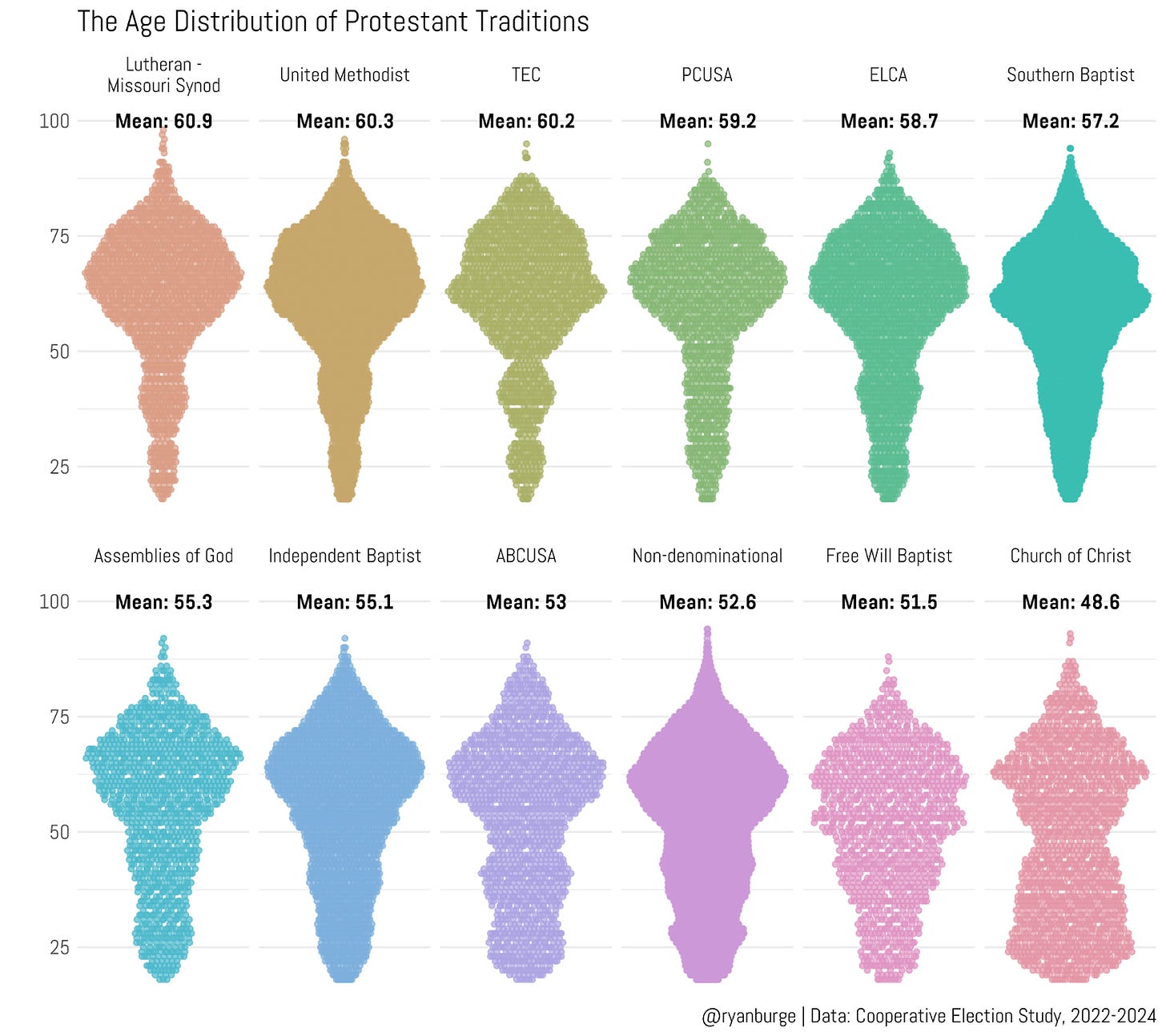

One other aspect of non-denominational Christianity that’s often pointed to as a strength is racial diversity. Many of the churches featured on television show people from all backgrounds worshiping together in the same congregation. That can certainly be a sign of a positive future, especially as the United States continues to become more racially heterogeneous in the years ahead.

But what does the data say?

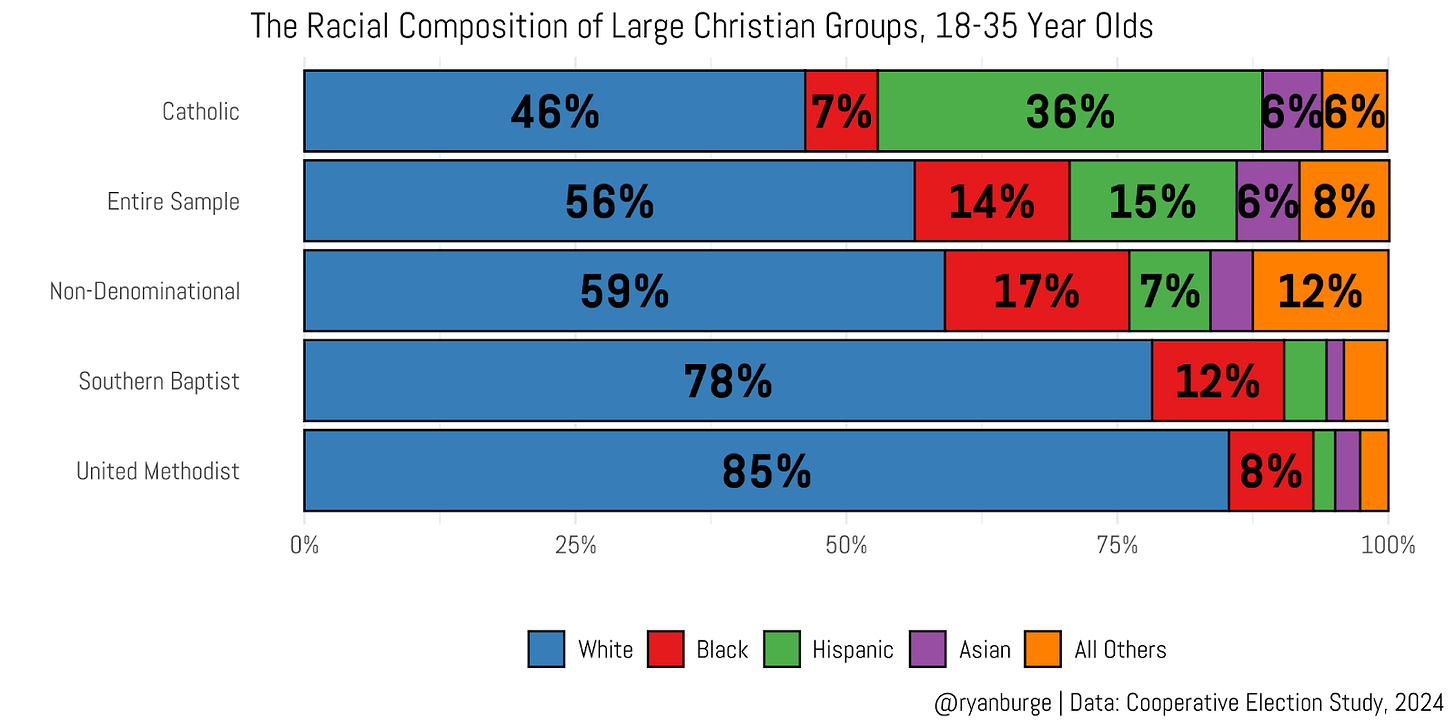

In 2008, 74% of non-denoms were white. That’s noticeably lower than the United Methodists, who were 90% white, and the Southern Baptist Convention, at 80%. The only group that was more racially diverse at the time was the Catholic Church, which was just 71% white. But Catholics and non-denoms differ in the type of diversity present in their pews. Among Catholics, 21% were Hispanic and just 3% were Black. Among non-denoms, 13% were Black and 7% were Hispanic.

Every denomination I examined was more racially diverse in 2024 than in 2008. The United Methodists were six points less white. The Southern Baptists dropped by three points. Among non-denominational Protestants, 71% identified as white—a three-point decline from 2008. For Catholics, the white share fell to just 64%, the lowest of any of these traditions.

But that still doesn’t tell the whole story. What may be the most encouraging data point for the future of non-denominational Christianity comes from looking at the racial composition of young adults within each of these traditions.

I have to point out that the Catholic Church is absolutely killing it on this metric. Just 46% of Catholics ages 18–35 say they are white—that’s ten points lower than all younger adults in the sample. Obviously, the biggest driver of that diversity is the Hispanic population. More than one-third of young Catholics are Hispanic, which is 21 points higher than the rest of the sample.

But non-denominational Christians show a tremendous amount of diversity as well. Only 59% of young non-denoms are white, which is just barely higher than all younger adults overall. They have strong representation among African Americans and those in the “all other” category, too. Where they lag is among Hispanics: just 7% of younger non-denoms identify as Hispanic.

When you compare non-denominationals to the two largest Protestant denominations—the United Methodists and the Southern Baptist Convention—you can see that non-denoms will have a huge racial advantage going forward. Both the UMC and the SBC are overwhelmingly white among young adults: 85% for the former and 78% for the latter. A denomination that has an overabundance of white young adults is drawing from a smaller overall market than those that are more racially diverse. That dynamic will likely only accelerate the decline of both the SBC and the UMC.

What about attendance, though? Before I get to that graph, I need to air a grievance about a worrying trend in survey data. It used to be the case that datasets like the GSS offered a lot of nuance on these questions. Denominational variables were broken down into groups like the SBC, UMC, or ELCA. That’s no longer true. Instead, the GSS now “bins” those traditions into much larger denominational families. So we’re left with categories like Baptists, Methodists, and Lutherans.

Why do they do this? The biggest reason is that lawyers have convinced them this helps mitigate privacy concerns. The logic is that if someone can be identified as a 45-year-old Black woman living in Georgia who is Seventh-day Adventist, it might be possible to track that person down. In other words, they can’t guarantee anonymity. That strikes me as ludicrous on its face—but I’m not a lawyer. Still, this shift is going to make fine-grained analysis much harder going forward, and it’s driven by a level of concern about data privacy that defies common sense. But here we are.

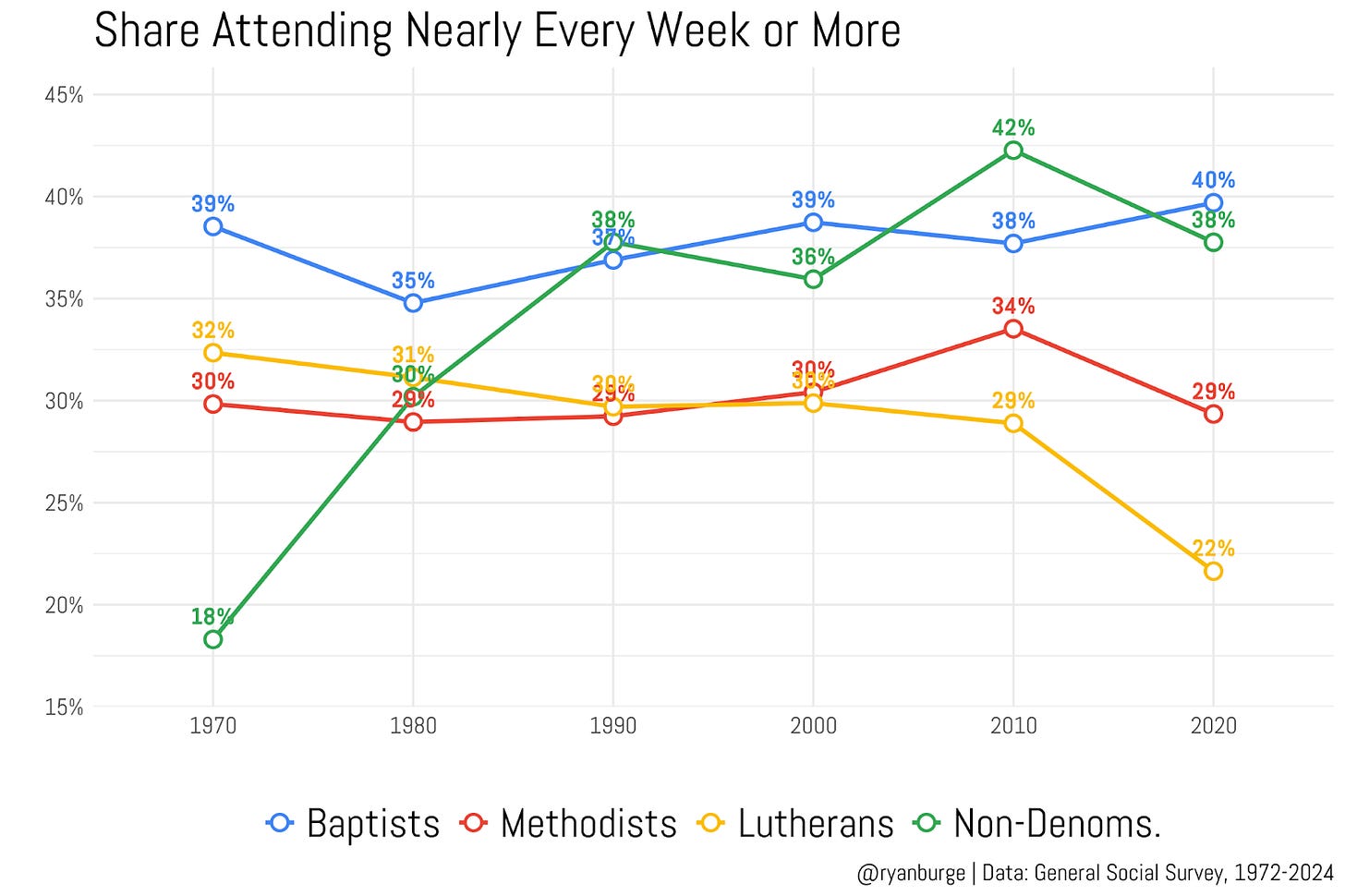

Anyway, rant over. Let me show you weekly attendance over time among Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, and non-denominational Christians.

Non-denoms really stood out in the 1970s because they weren’t all that religiously active. In fact, only 18% were regular church attenders. That was 12 points lower than Methodists, 14 points behind Lutherans, and a whopping 21 points below Baptists in the sample. However, non-denoms caught up quickly. By the 1980s, they were right in the middle of the pack, with about 30% attending nearly every week.

From there, non-denominational attendance continued to climb. It reached 38% in the 1990s, which actually put them on par with Baptists. That pattern has continued over the last twenty years: non-denoms and Baptists are just as likely to be weekly attenders. The figure has bounced around a bit, but it’s usually right around 40%.

In contrast, Lutherans and Methodists have fallen behind on church attendance. In the 2020s, just 29% of Methodists were attending weekly, compared to only 22% of Lutherans. From this vantage point, it’s fair to say that non-denominational attendance now sits at the very top of the range for Protestants. That certainly wasn’t the case prior to the 1990s.

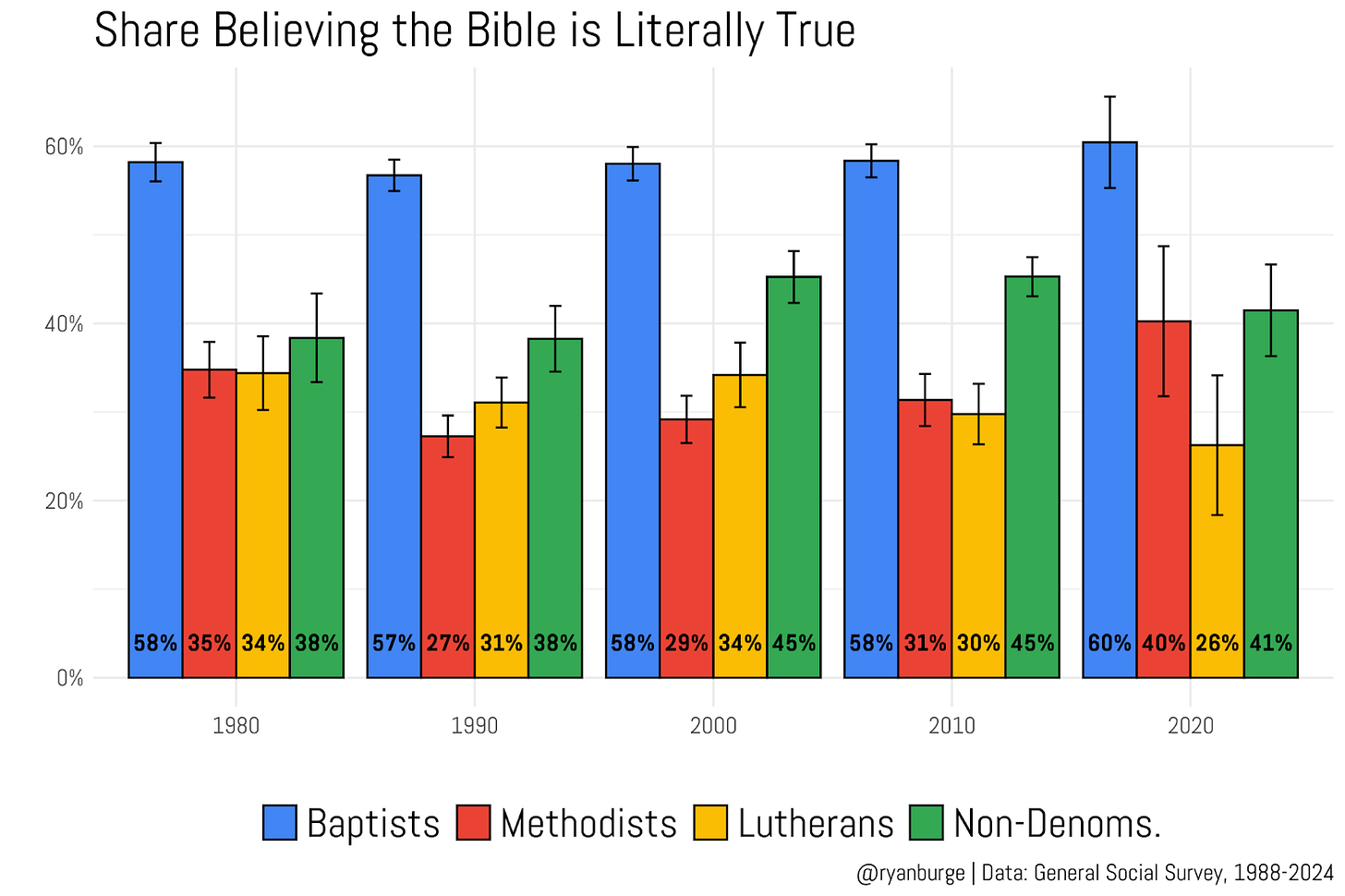

There’s one other metric worth exploring: respondents’ views of the Bible. The question offers essentially three response options, and I calculated the share who said that the Bible “is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word.”

Baptists have always led on this metric. In the 1980s, 58% of them chose the literalist option—that was twenty points higher than any other tradition I examined. What’s striking is how little these numbers have shifted over time. Baptists have never dropped below 57% on literalism and have never risen above 60%. That kind of consistency is remarkable.

For non-denoms, belief in a literal Bible has crept up slowly over time. It was 38% in the 1990s, then rose to 45% in both the 2000s and the 2010s. It dipped slightly to 41% in the most recent couple of years, but that change isn’t statistically significant. Among Methodists and Lutherans, levels of biblical liberalism have also remained largely unchanged—just at a lower level than among Baptists and non-denoms.

So what can we conclude about the rise of non-denominational Christianity from these data?

They have age on their side. Non-denoms are noticeably younger than many of the largest denominations in the United States, and they have a substantial share of younger adults in their congregations who will help offset losses from the Baby Boomers.

Second, their racial diversity—especially among young adults—is a real strength. In many ways, non-denoms already look a lot like the future of America.

Finally, when it comes to attendance and belief, it’s fair to say that non-denoms are moving toward the evangelical median. Attendance has risen significantly, and the share who believe in a literal Bible has increased in a meaningful way over time.

In short, the future of American evangelicalism may not be found in the Southern Baptist Convention or the Assemblies of God. It may be found instead in places like The Journey, The Bridge, I Heart Church, Airborne Church, Enjoy Church—and hundreds of similar congregations popping up all over the United States.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

I spent 36 years of my after-college life in large non-denominational churches before moving to a mainline church 2 years ago. So doing the math you know I'm not exactly young.

Looking back, what issues did I not consider close enough or overlooked:

1) Church was focused on a performative Sunday service.

2) Church was centered around a single pastor that had very little accountability, even if there was a "board".

3) Church had very little financial accountability to the membership. A typical audit report would fit on a 3x5 card.

4) Very little teaching on theology, what we believe, why we believe this or that. Is the Bible inerrant? Why do we believe in eternal conscious torment?

5) Church follows the fads. Small groups, coffee shops, etc. Whatever is in.

6) Most "ministries" were internal and had little to do with the community.

7) Systemic and/or social issues? No thanks, we just love Jesus and can't wait to get to heaven.

Wondering. I wonder if the non denoms have a common view about religion besides describing themselves as Christian And what do they mean by Christian? It strikes me that many people are bored by theology and are seeking feeling in its place. One could describe this as a spiritual connection or a sense of community of the elect.

What makes a church Christian is it a belief in Jesus or a belief in the Trinity? Some Catholic theologians that I have read recently speak of Christomonism, meaning where Jesus has largely displaced the Trinity. Is this an evolution of Christianity or a new thing?

When people say they believe that the bible is the literal word of God do they know what is in the Bible or do they even care that much or is this more of a political statement, kind of a line in the sand? Do they think the English text of the Bible is the word of God?