The Sharp Decline in Transgender Identification Among Young Adults

What the latest data say about Gen Z, gender identity, and a post-pandemic correction.

I am running a holiday special - 20% off an annual subscription to this newsletter. That brings the cost down to just $48 per year. Take advantage by clicking this button:

Back in October, there was a splashy data finding from several surveys of young people: they were less likely to identify as transgender in the most recent data. Eric Kaufmann reached that conclusion using results from a poll of Andover Phillips Academy students, data from Brown University, and a large questionnaire fielded by FIRE. Then Jean Twenge ran the same analysis on college-aged respondents in the Cooperative Election Study and came to a very similar conclusion — the share of 18–22-year-olds who identified as transgender has dropped noticeably between 2022 and 2024.

To be honest, the three surveys Kaufmann used aren’t what I’d call high quality. The Andover and Brown data are literally just censuses of each college’s student body, and while the FIRE data are large (over 50,000 respondents), they’re not truly representative because they only include young adults currently attending one of fewer than 600 universities.

But the Twenge analysis really caught my attention because the Cooperative Election Study is a much higher-quality dataset. I use it all the time in my own work, not just because the 2024 sample included 60,000 respondents, but because it’s administered in a way that produces a genuinely representative cross-section of the United States.

So, my purposes today are twofold. First, I want to replicate and validate the finding that trans identity is declining among young adults. Second, I want to dig into why that’s happening.

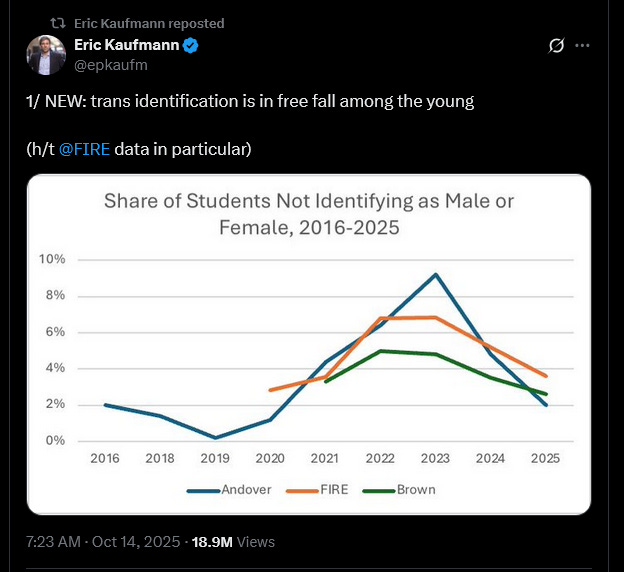

Let’s tackle the first question. Has there been a noticeable decline in the share of 18–22-year-olds who identify as transgender over the last couple of years? The answer is unequivocal: yes.

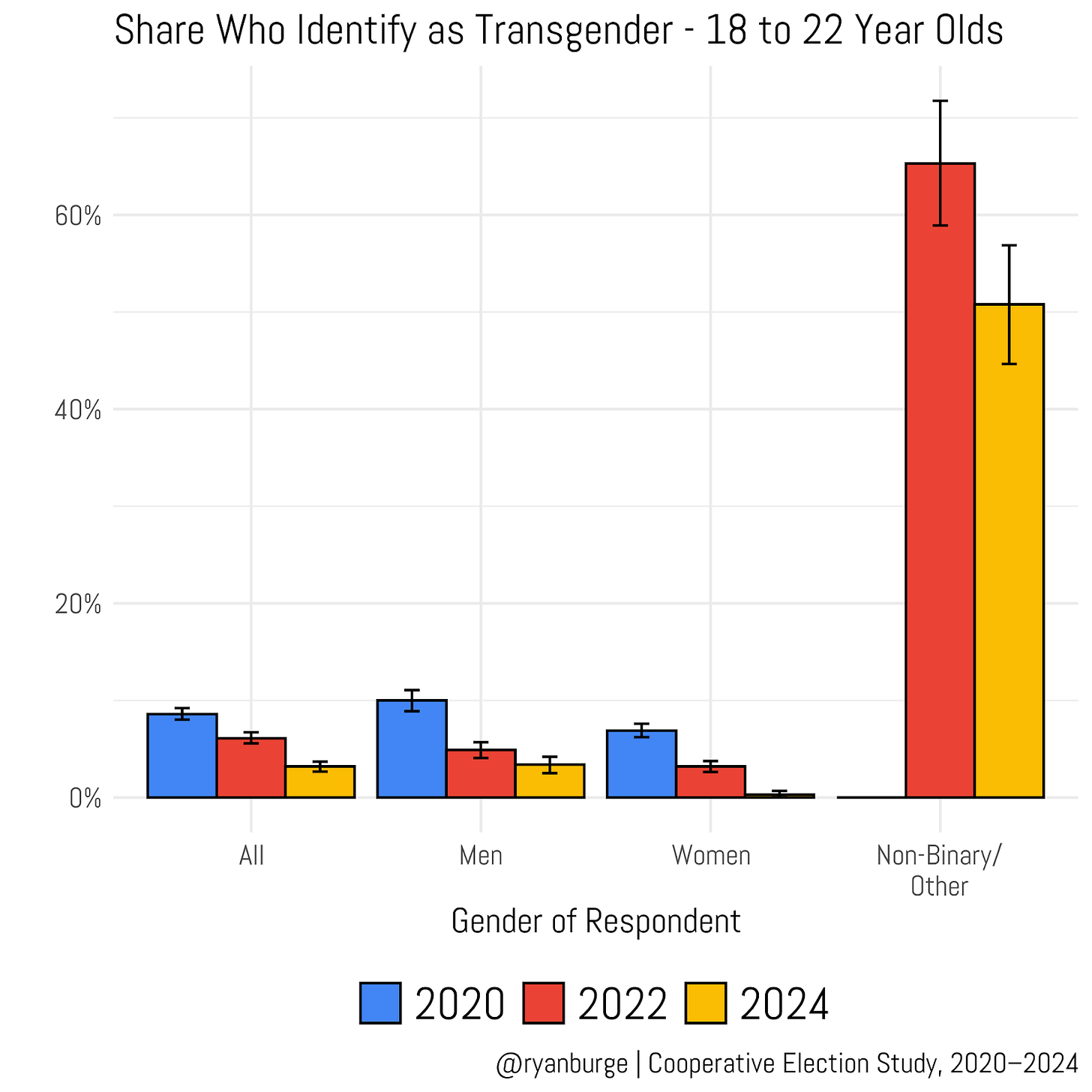

In 2020, 8.6% of 18–22-year-olds said they were transgender. That was, without question, the high-water mark. Just a year later, the share dropped to 5.6%, and the 2022 estimate was 6.1%—statistically indistinguishable from the previous year’s result.

Now, this is an important point: the Cooperative Election Study didn’t include that question in the 2023 wave, but it returned in 2024. In that most recent data, just 3.2% of young adults identified as transgender. That’s a decline of more than five percentage points between 2020 and 2024. And these aren’t small samples, either—there were 4,140 young respondents in 2020 and 3,135 in 2024. The difference is, of course, statistically significant.

I also thought it would be helpful to zoom out beyond just 18–22-year-olds and look at broader age cohorts. Among 18–25-year-olds, 7.8% identified as transgender in 2020, compared to 3.7% in 2024. Expanding to 18–30-year-olds, the drop is 3.4 percentage points (from 6.4% to 3%). Among 18–40-year-olds, it’s a 3.2-point decline.

What about the full sample? In 2020, 2.5% of all adults said they were transgender. In 2024, that number fell to just 1%. So the sharpest decline is clearly concentrated among the youngest slice of the American electorate—and the share keeps dropping as older respondents are included.

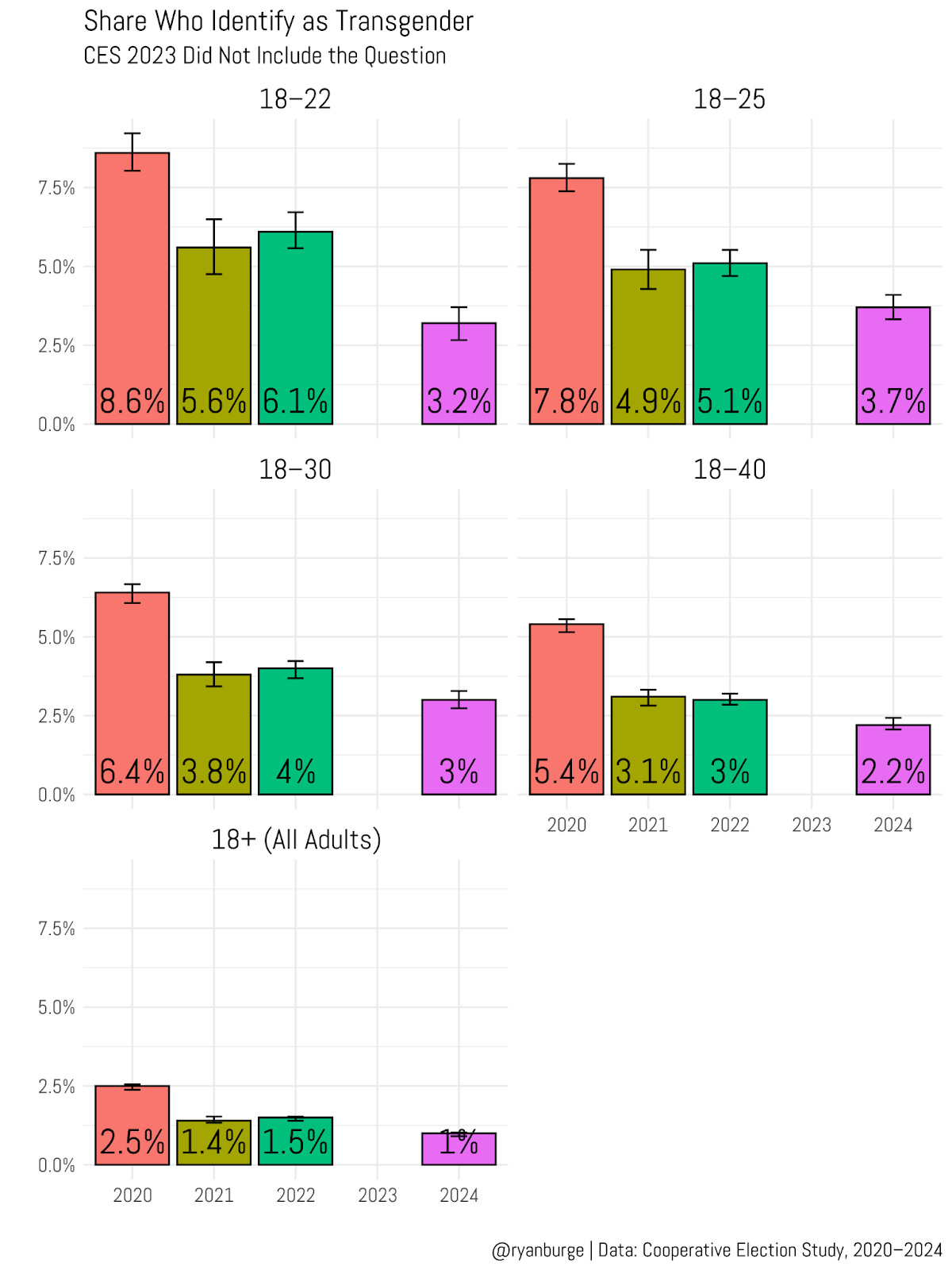

Let me show you another angle on this—broken down by five-year birth cohorts in 2020 versus 2024. What’s striking is that even among people who are decidedly not “young,” there was a noticeable drop in trans identification. For instance, among respondents born in the 1970s, about 1.6% said they were transgender in 2020; by 2024, that had fallen to just 0.3%. For those born in the late 1980s, trans identification dropped from 4.8% to just 0.9%. So this isn’t just a phenomenon limited to the very youngest adults—there were significant declines among people in their thirties and forties as well.

Of course, the biggest drop in raw numbers still comes from the younger part of the sample. Among those born between 1995 and 1999, 7.5% identified as transgender in 2020, but that figure fell by two-thirds in 2024, down to just 2.3%. For respondents born in the early 2000s, trans identification dropped from 8.5% to 4.1% over the same period.

So yes, the decline was most acute among the youngest adults, but it wasn’t only them. The drop was widespread, showing up even among people born as early as 1985.

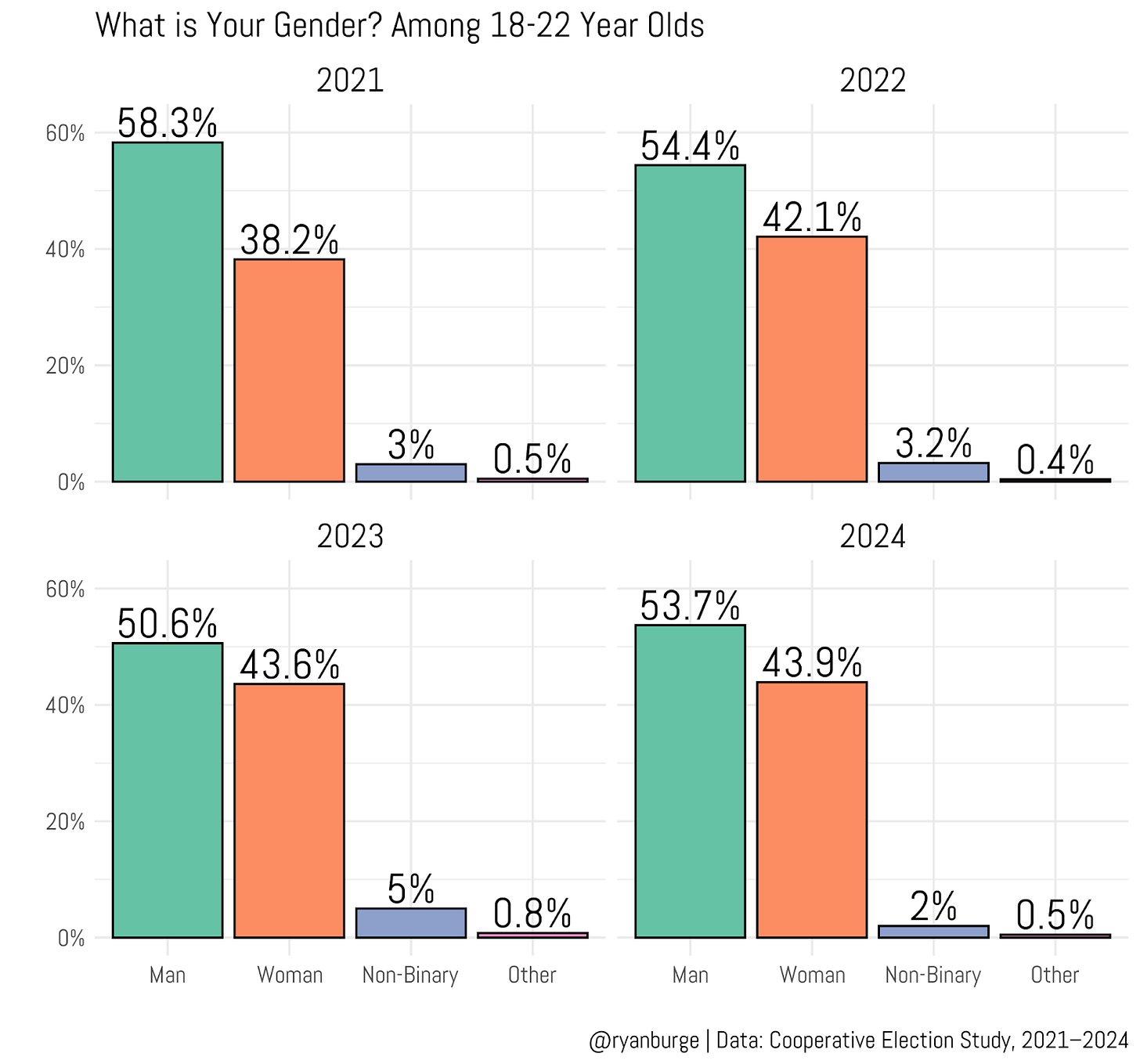

Let me poke at this from another angle, though. The Cooperative Election Study used to offer just two response options to the question “What is your gender?”—“man” and “woman.” But in 2021, they expanded it to four categories by adding “non-binary” and “other.” Here’s how 18–22-year-olds have responded to that question over the past four years.

What we really want to focus on here are the last two categories. In 2021, 3% of respondents identified as non-binary and another 0.5% selected “other.” What’s surprising is how little those numbers have changed since then. In 2022, the non-binary share was 3.2%—statistically indistinguishable from the previous year. It jumped to 5% in 2023, but that turned out to be temporary, falling back to 2% in the most recent data.

If you combine the “non-binary” and “other” categories, the totals are 3.5%, 3.6%, 5.8%, and then 2.5%. I’m not sure we can say anything meaningful about a trend based on that pattern—especially since the highest estimate came in 2023 and the lowest in 2024. The picture looks pretty muddy when we focus on this single metric.

But let’s cross that gender question with the separate binary question about transgender identification.

As mentioned earlier, 8.6% of young adults said they were transgender in 2020. By 2024, that had dropped to 3.2%. Among young people who identified their gender as male, trans identification fell from 10% in 2020 to 3.4% in 2024. For young women, it dropped from 6.9% in 2020 to just 0.3% in 2024. And that’s not a typo—out of 3,914 respondents between the ages of 18 and 22, only six identified as both a woman and transgender (weighted).

So, it becomes pretty clear where a large share of transgender identification is coming from: respondents who listed their gender as “non-binary” or “other.” The gender question only offered two options back in 2020, so we can’t make a full comparison that far back. But among people who did not identify as a man or woman, 65% said they were transgender in 2020. In 2024, that figure dropped to 51%. The difference is statistically significant, even though both groups are relatively small in size.

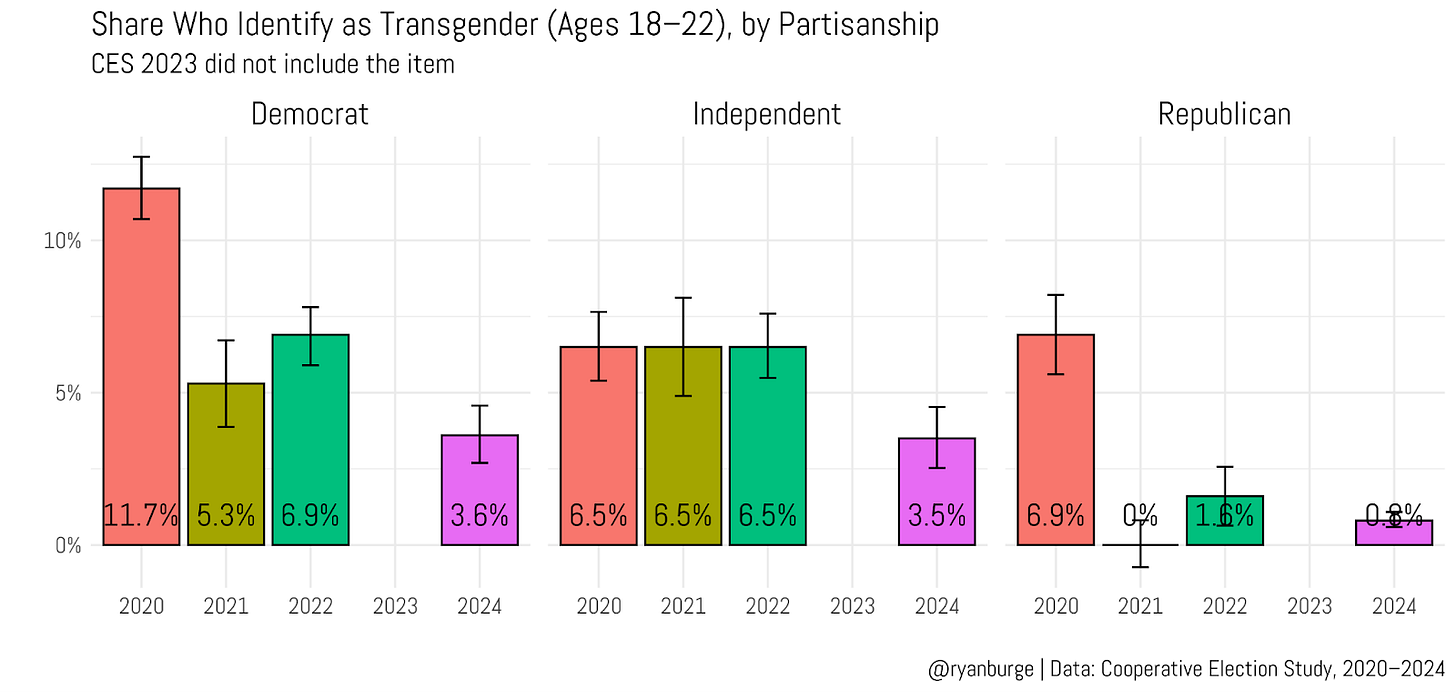

Now, let’s pivot to the second goal of this piece—trying to understand what factors might be driving this sharp decline in transgender identification among the youngest adults. One possible explanation could be politics. To explore that, I divided the sample into Democrats, Independents, and Republicans.

Among young adult Democrats in 2020, nearly 12% identified as transgender. That share had already been cut in half within the next two years, and by 2024 it had fallen to just 3.6%. In other words, an 18–22-year-old Democrat in 2020 was three to four times more likely to identify as transgender than a young Democrat in 2024. That’s a dramatic shift.

You can also see a noticeable drop among political independents. Interestingly, the estimates from 2020, 2021, and 2022 were identical—6.5% in each year. But by 2024, that number had fallen to 3.5%. It’s worth noting that there was essentially no difference in transgender identification between young Democrats and young Independents.

The Republican sub-sample tells a different story. In 2020, 6.9% of 18–22-year-olds who identified as Republican said they were transgender. After that, the number basically vanished. In 2021 it was statistically zero, and in 2024 it was just 0.8%. I don’t want to stray too far into hot-take territory, but it seems that around 2021 the Republican Party drew a clear “bright line” on this issue—and when that happened, the idea of trans Republicans all but disappeared.

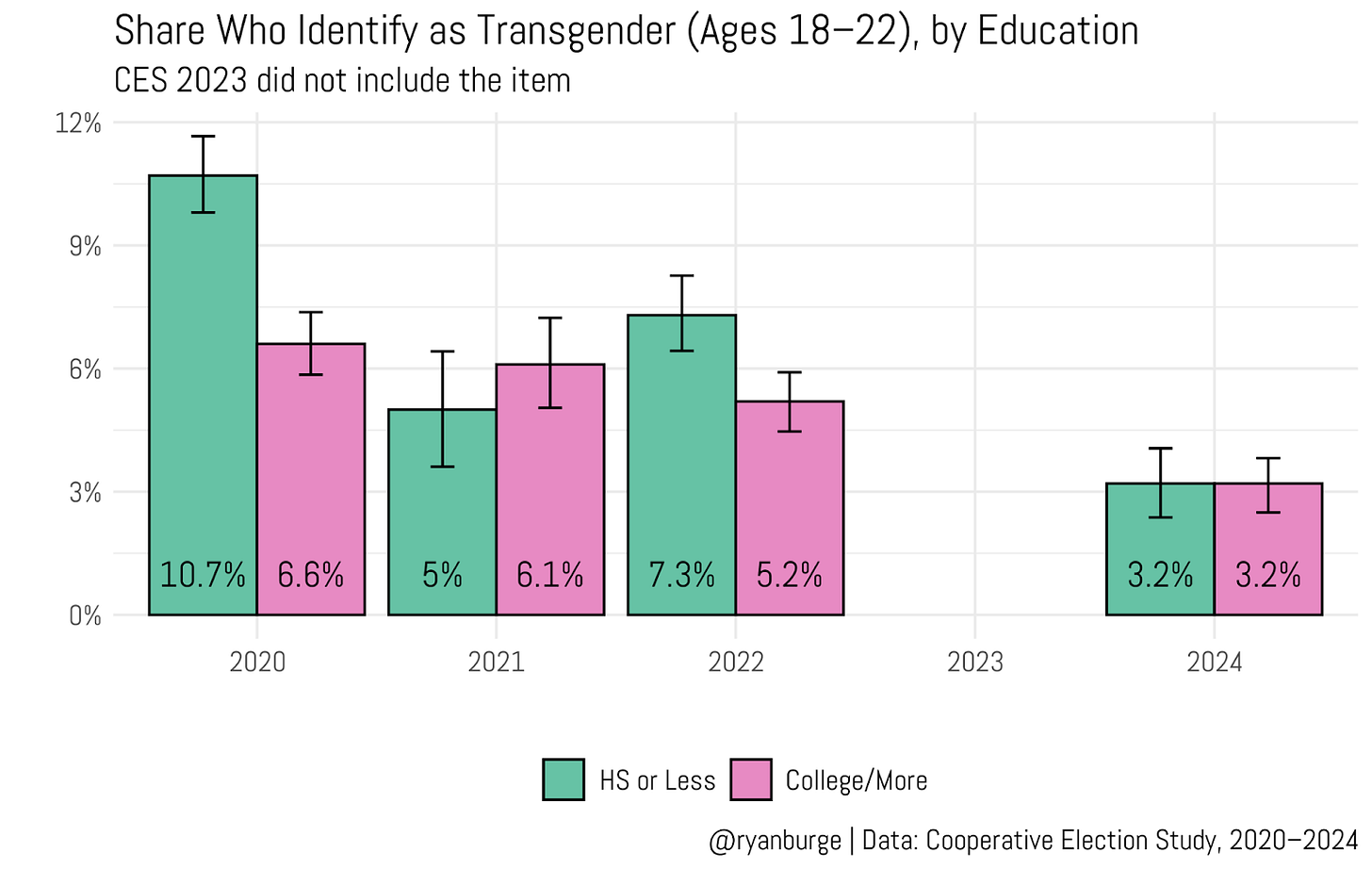

Now, what about education? I divided the sample into two groups: young adults with no more than a high school diploma and those who had attended at least “some college.” It’s not a perfect measure of socioeconomic status, but it’s a pretty solid proxy.

Here’s what’s really interesting to me: in the 2020 data, young people who weren’t going to college were actually more likely to identify as transgender than those who were furthering their education. Among the former group, 10.7% identified as transgender compared to 6.6% among those enrolled in college.

But that was the only time there was a clear educational divide. By 2021, the gap had narrowed to just a single percentage point. In 2022, 7.3% of people who stopped at high school identified as transgender, compared to 5.2% of college-going 18–22-year-olds. And by 2024, both groups were at 3.2%. In other words, they’ve converged—there’s no educational difference at all now.

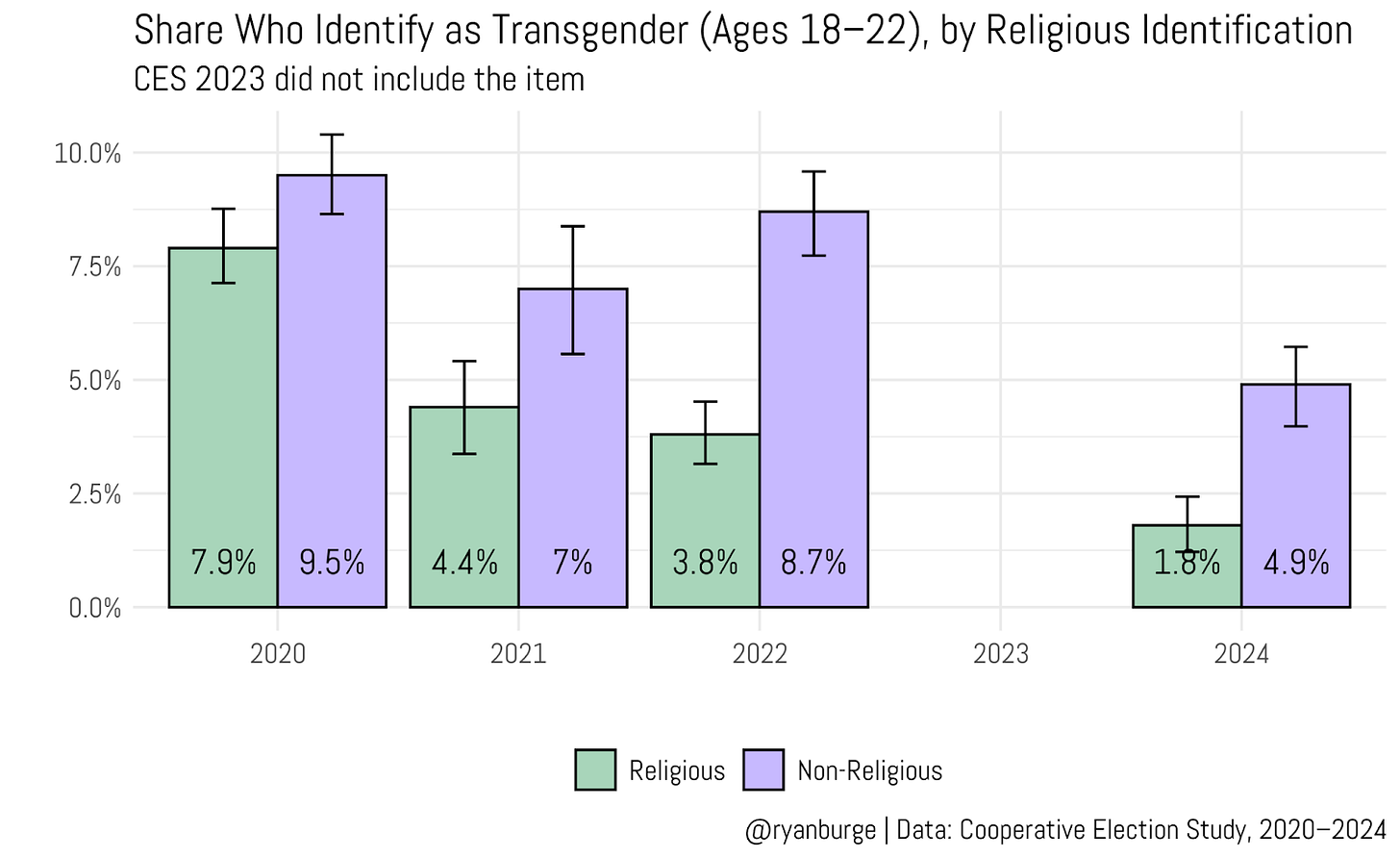

And you know I had to throw a religious variable in here, right? I split the sample into those who identified with any religious tradition and those who reported being atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

In 2020, while the non-religious were slightly more likely to identify as transgender than the religious (9.5% vs. 7.9%), that gap wasn’t statistically significant. But that changed in the following years, when the difference did reach statistical significance. In 2021, the gap was 2.6 percentage points. In 2022, it grew to 4.9 points. And in the most recent data, 4.9% of non-religious 18–22-year-olds said they were transgender, compared to just 1.8% of their religious peers. That’s a big decline for both groups between 2020 and 2024.

I think it’s fair to say, with a good amount of confidence, that the share of college-aged Americans identifying as transgender has declined in both a statistically and substantively meaningful way over the last few years. But as I worked through the data, I kept coming back to the same thought: 2020 was an outlier when it comes to transgender identification. You can see it clearly across all these graphs.

Maybe it was COVID. That was such an odd time in America—for a whole bunch of reasons. I remember telling one of my colleagues at EIU that one thing the pandemic taught young people was this: all these rules are completely made up and can be ignored if we collectively decide to do that.

When you’re presented with a much more elastic plausibility structure, the implications are hard to grasp. Maybe this is one of them. But what’s also clear to me is that things seem to have snapped back to some kind of baseline.

As Forrest Gump famously said, “And that’s all I’ve got to say about that.”

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

Correlation isn't causation, and all that jazz, and I'm not sure how you'd go about testing this: I am not surprised that the share of people self-identifying as trans (especially on a survey; "Where is this information going and who is tracking it?") is in decline given the increasing levels of fear I hear in the trans community as a result of our current political environment.

Of course it's impossible to talk about the "why" of any quantitative research without solid, well-conducted qualitative follow-up. But we get to possibilities by first looking at trends.

I'm very interested in this conversation because I was a proponent of inclusion of gay humans in Christian communities in the 1980s (when it could end your own inclusion to be so). Back then there was a study that created relatively safe ways for people to report on sexuality in far-ranging parts of the world, with important results: roughly 9% of every population self-reported some form of "sexual minority" status.

I suspect that today the study would be limited in that we had no terms for aros or polys back then, and language helps people determine their identities.

That leads me to wonder about the spike in U.S. folks identifying as transgender - are they in more clearly-defined groups today then people were aware of back in 2020? Ryan seems to find this with "non-binary" and "other" categories, to an extent. Also, we know that for a large percentage of people, healthy sexual development can include times of uncertainty and questioning of their own sexuality (why anti-gay groups are always destructive, not to mention some who seem to base their identities on gay advocacy). Did awareness and support for transgender persons lead those who felt unsettled in their sexuality to claim transgender identity?

Good research isn't judged by the solidity of its conclusions, but by the complexity of the questions it raises. Thank you for this, Ryan.