The Political Takeover: Why Ideology, Not Faith, Drives the Culture War

The Liberal-Conservative Divide Is the True Engine of Polarization, Not Religious Affiliation

No term takes me back to my graduate school days like the “Culture War.” And for good reason: it was one of the biggest methodological debates in political science. Two camps emerged—one argued that polarization had completely infiltrated American society. It wasn’t just a phenomenon of the chattering class, but it was also clearly evident among rank and file Americans across the country. These folks were often called maximalists, and their position was typified by Alan Abramowitz’s papers. If you want one single source to read about this view, I would recommend his book The Disappearing Center, published in 2010.

The other position was articulated in the aptly titled Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America (first published in 2005 and revised several times since). You can probably guess the major thesis there: polarization has occurred at the elite level, but it really hasn’t seeped down into the mass public. I actually do take my stand on this position in my new book The Vanishing Church, so pick up a copy.

But beyond the debate over who is polarized in the U.S., there’s an adjacent, and perhaps more critical, discussion I want to tackle today: What drives polarized views? There is ample reason to think that religiosity impacts views on topics like abortion, same-sex marriage, and gender identity. This, after all, was the impetus behind Pat Buchanan’s famous 1992 Culture War speech at the Republican National Convention.

The alternate view is simple: partisanship is more important than religion. According to this framework, a question about abortion access is not answered by seeking theological justification; instead, citizens take their cues from political elites regarding hot-button issues.

That’s what I am going to explore today by looking at a battery of four statements from the 2023-2024 Pew Religious Landscape Study:

Abortion: Do you think abortion should be...? (Coded “legal in all/most cases” as support.)

Trans Acceptance: Greater acceptance of transgender people... (Coded “change for the better” as support.)

Same-Sex Marriage: Do you favor or oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally? (Coded “strongly favor/favor” as support.)

Homosexuality Acceptance: Should homosexuality be accepted or discouraged by society?

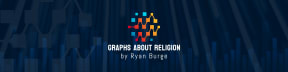

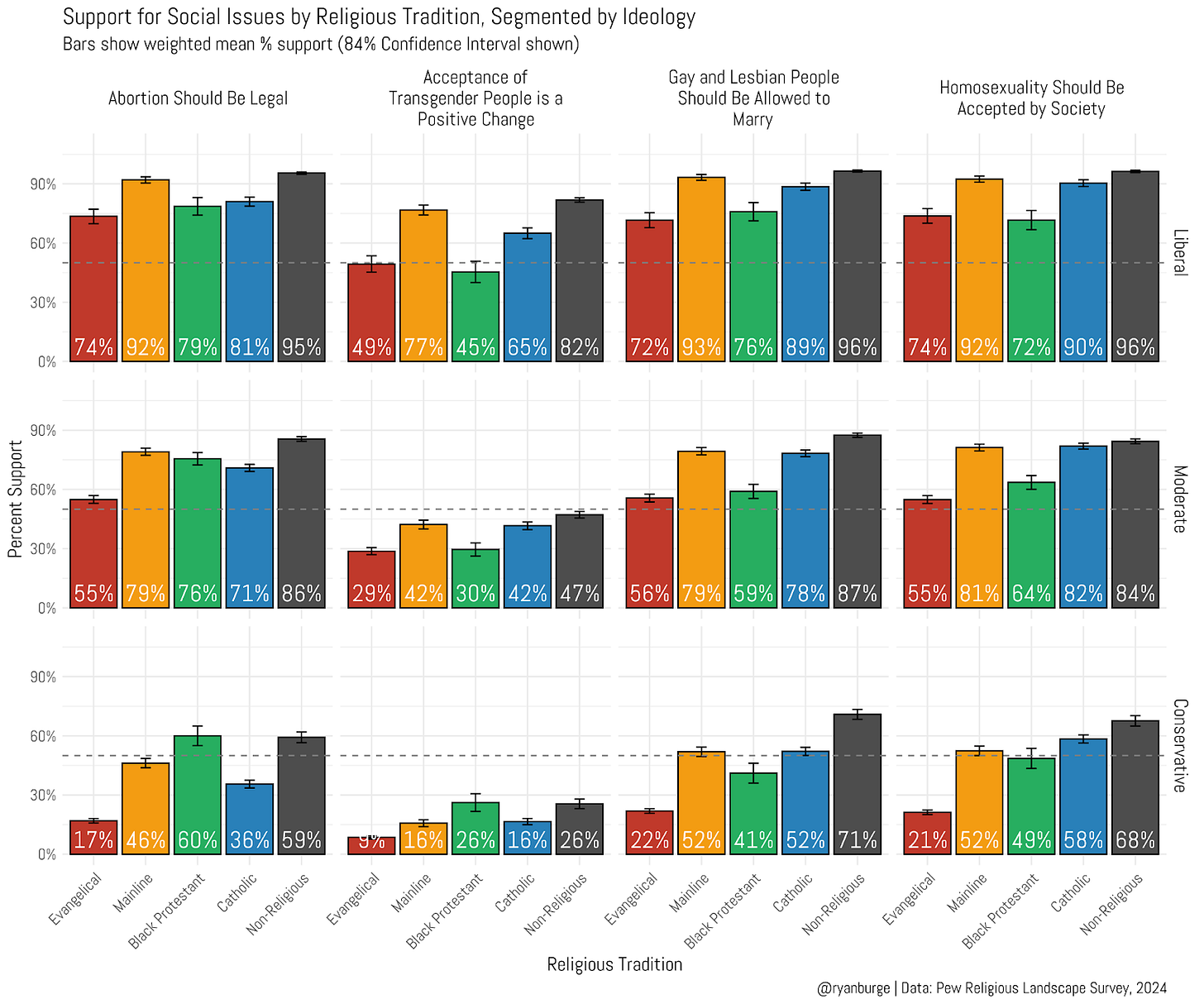

First, let’s look at the raw support for each of these social issues broken down by different Christian traditions and the non-religious.

One thing that is undoubtedly true is that the non-religious are more socially progressive than any Christian group. They are 13 points more likely to support abortion access than any Christian group and 18 points more supportive of transgender people than the most supportive Christian group.

It should come as no surprise that evangelical Christians were easily the most socially conservative of the bunch. Just one third favor access to an abortion—that’s 26 points lower than Catholics. Their views of gay marriage are twenty points to the right of Black Protestants, and only 18% of evangelicals think that acceptance of transgender people is a positive change for society. That’s 14 points lower than Black Protestants.

So, those numbers basically shake out the way one would expect, right? The non-religious are the most socially progressive, while evangelicals are the most socially conservative. Mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Black Protestants tend to fall between those two poles.

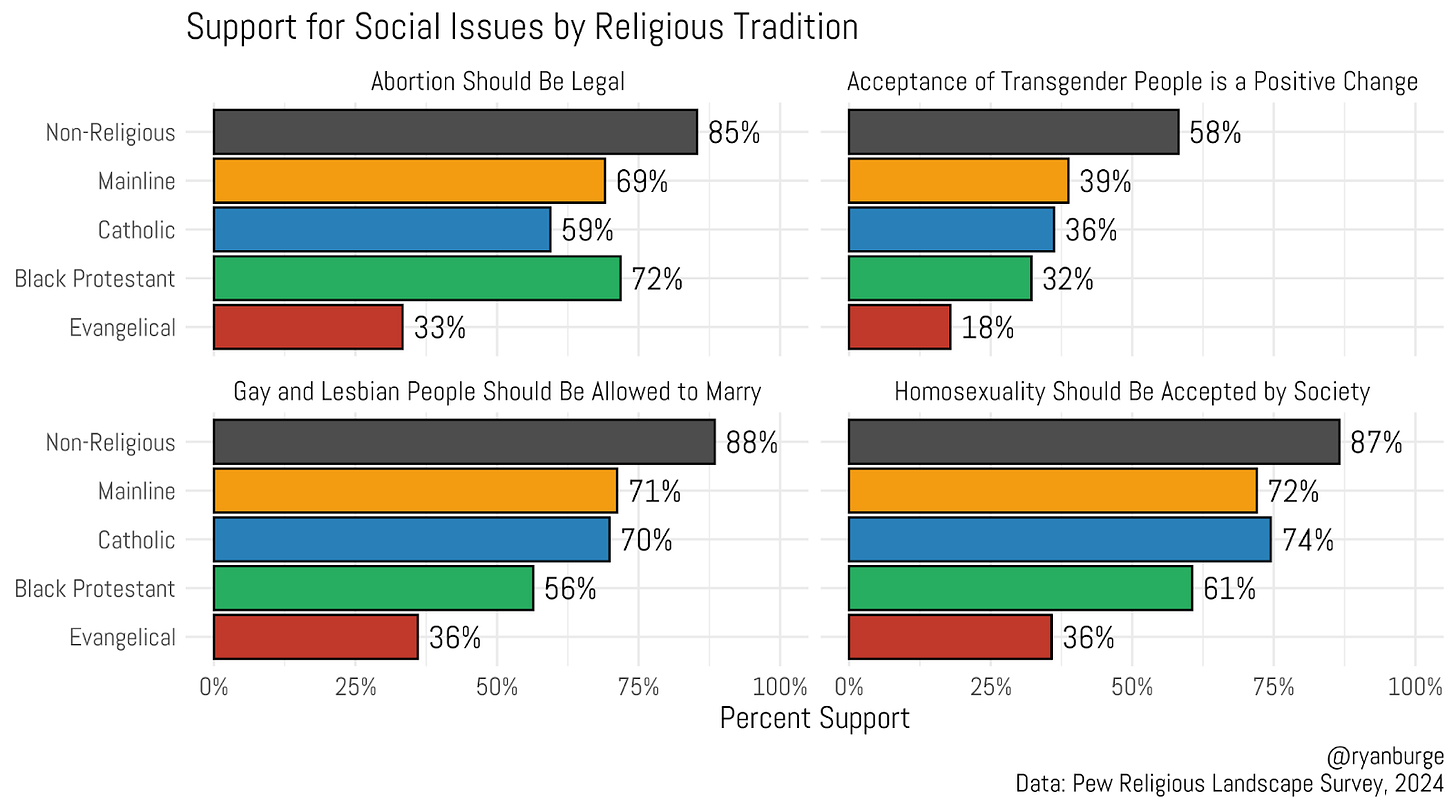

What happens when I throw age into the mix, though? Perhaps this is just a generational phenomenon, and young evangelicals are actually socially progressive.

Here’s one thing that I learned by doing this analysis: there’s almost no age gradient when it comes to support for abortion. Look at those results for Evangelicals! Whether they were born in the 1960s or the 2000s, only about a third are in favor of access to abortion. And that’s largely true across all religious traditions—younger folks look remarkably similar to older folks across the board. I’ve said this before, but abortion is this really odd issue that doesn’t work like other Culture War debates.

On other topics, like acceptance of transgender people, there’s a pretty noticeable age gradient. Younger Evangelicals are clearly more supportive than older Evangelicals. You can basically see that with most Christian groups, too. For instance, among Mainline Protestants, support doesn’t rise above 50% until you get to respondents who were born in the 1990s or later.

The finding that younger respondents are more progressive than older ones is replicated in questions about homosexuality, too. Note that among Evangelicals born in 1990 or later, about half favor same-sex marriage. Among those born in the 1940s or earlier, support is just 25%. That also appears in the statement “homosexuality should be accepted by society.” Older folks are just more socially conservative.

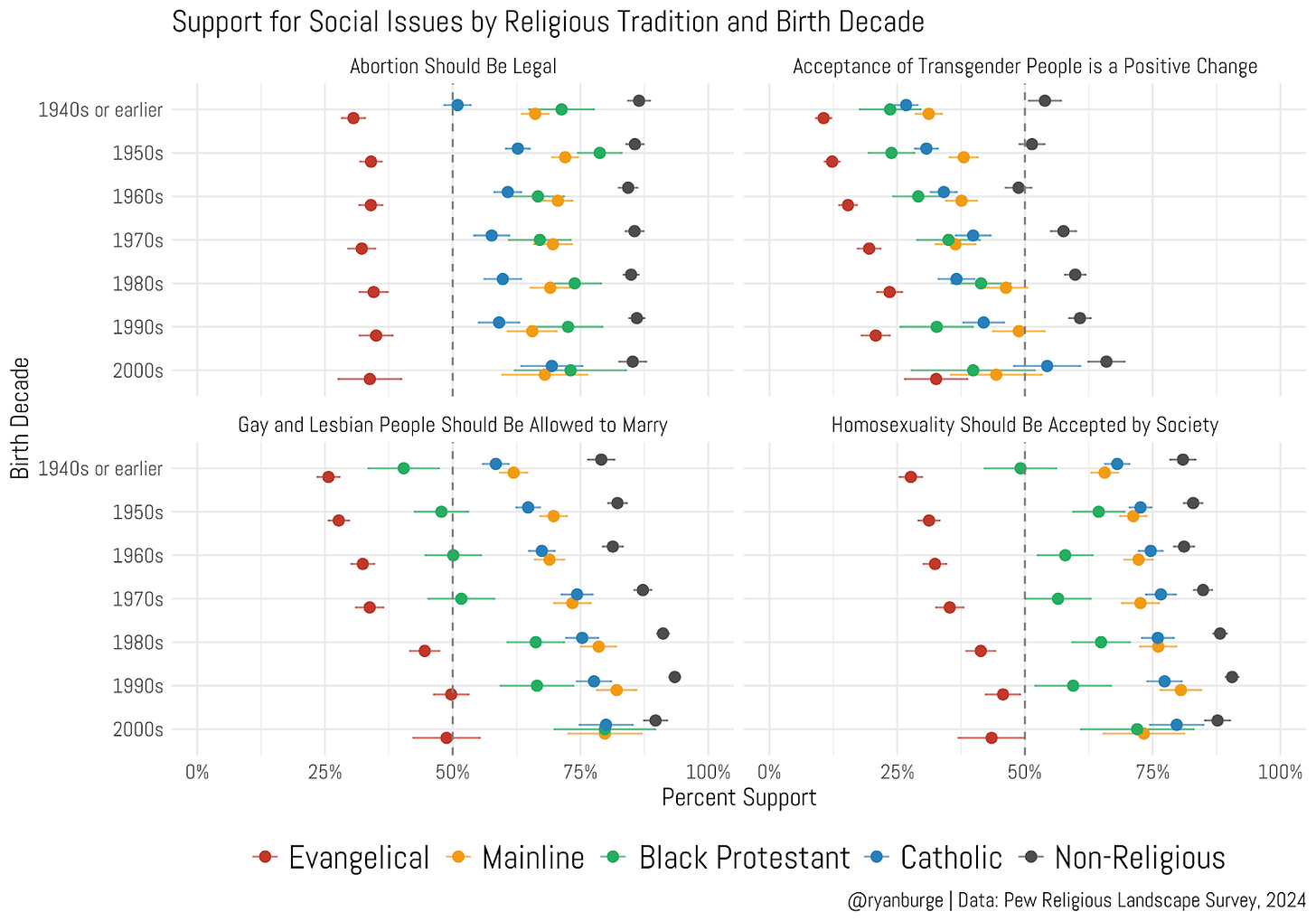

Now, of course, one could look at this analysis so far and say, “All this is really just masking political ideology. Evangelicals are conservative and the non-religious are liberal. That’s what is driving opinions on those topics.” And that person would be right, of course.

The descriptive data clearly shows that Liberals and Conservatives occupy opposite poles on these issues. On the question of the legality of abortion, 90% of Liberals are in favor compared to just 34% of Conservatives. Do notice, though, that Moderates are much closer to the permissive view here, with support over 50%. That tendency—Moderates being noticeably more socially liberal—is a common refrain here across issues like gay marriage and general acceptance of homosexuality. (As an aside, I suspect this reflects a constituency that is often socially progressive but economically conservative, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

But you can see that acceptance of LGBT folks is a part of liberal orthodoxy now. Over 90% favor same-sex marriage and acceptance of homosexuality. Consider the fact that trans acceptance lags behind the other liberal positions, though. The “acceptance of transgender people” statement is the only one where a majority of Moderates are not supportive (falling below the 50% line). This confirms it operates on a different, more contested axis than the other three issues.

Now, let’s collapse these two variables—religious affiliation and political ideology—into a single bit of analysis. To determine which factor truly drives public opinion when both are present, we will use weighted logistic regression. Our goal is to isolate the independent effect of each variable, holding the other constant, using the same four statements as our dependent variables.

Here’s what immediately jumps out to me: the bars are taller across the top row (those are liberal respondents) and they are much shorter across the bottom row (those are ideologically conservative folks).

Look at Evangelicals and abortion. Among liberal Evangelicals, 74% favor access to abortion services. Among conservative Evangelicals, that share drops precipitously to just 17%. On the statement of “homosexuality should be accepted by society,” the ideological gap among Evangelicals is a chasm: among liberals, 74% agree, but for conservatives, it’s just 21%.

And it’s not just Evangelicals. The ideological divide is there across every Christian group. For instance, among liberal Catholics, 65% of them embrace transgender people. Among conservative Catholics, support is only 16%. For Mainline Protestants, support for same-sex marriage drops by 41 points when moving from liberals to conservatives. This is a really consistent finding—ideology matters a whole bunch when shaping views about social issues.

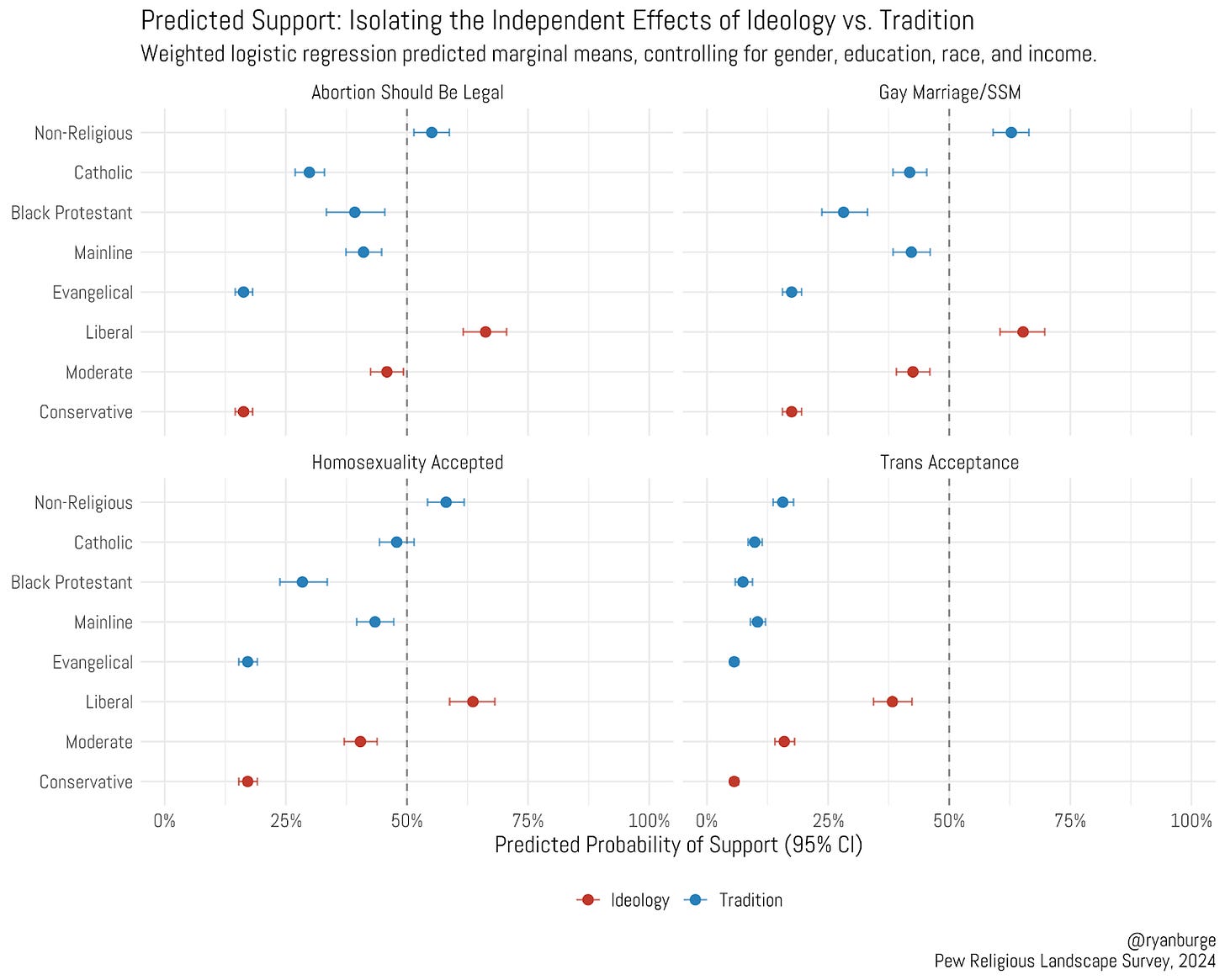

So, I had to try and tease out how big the effects are for ideology versus religious tradition on these hot-button issues. To do that, I specified a weighted logistic regression model for each of the four dependent variables. I controlled for all the usual suspects like gender, education, race, and income.

What I am plotting for you is the predicted probability of support when controlling for other factors. This helps us get to the heart of the matter: Is it politics that drives views on social issues more than religion? The thing you want to look at here is the spread between the point estimates in blue (religious tradition) compared to the spread between the points in red (political ideology).

I think that the question of Trans Acceptance is the “cleanest” of the four and really tells a compelling story. Look at the plot points for religious tradition—they don’t vary that much. You do see that the non-religious are slightly more supportive than Evangelicals. But why is the spread so big in the first graph that I showed you and so small here? Well, it’s because we controlled for political ideology this time around. In other words, religious tradition is really just the “front-facing” variable, when it’s Liberals vs. Conservatives behind the scenes.

In the graph above, you just want to look at the visual gaps, but the actual percentages of predicted support for each coefficient are shown in the table here:

When we isolate the effect of political ideology from religion and other factors, the spread in predicted support for Trans Acceptance is massive:

A Liberal is predicted to support acceptance at a rate of 69.5%.

A Conservative is predicted to support acceptance at a rate of 14.5%.

This 55-point gap confirms that political identity is the overwhelming factor driving views on this issue, independent of religious tradition.

There’s also another surprising finding in our table: among the non-religious, predicted support for trans acceptance is just 35.8%. That can’t be right when looking at the first graph where raw support was around 58%! But here’s why the number is so low: we are controlling for ideology now. It’s not simply being non-religious that drives up support for trans folks; it’s being liberal (which is highly correlated with being non-religious).

I feel like a broken record when I say this, but people’s views of social issues are not being shaped by a coherent theological worldview. They are being shaped by how leading voices in their political tribe are talking about them. Or, said even more simply: politics matters more than religion.

If you grabbed a random person on the street and asked them, “Do you think gay and lesbian people should be allowed to be married?” What would be a better question to correctly guess their answer?

What is your present religious affiliation, if any?

ORWould you describe your political views as liberal, moderate, or conservative?

From this data exercise, I think we know which question has more predictive power.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

Yes, but that’s basically a tautology. The label “Conservative” is essentially defined by how people answer questions about abortion, affirming trans kids, and gay marriage. The interesting finding isn’t that ideology is correlated to how people answer ideological questions. Rather, it is that ideology is correlated with religion.

Great as always Ryan. As always, look for the incentives. Who benefits from a sharply divided country? As well as political races to be won with increasingly simple rhetoric there's a lot of money to be made in the media and elsewhere by having two well defined camps fighting each other. Not to mention that it's a distraction from any possibility of coming together to fight even broadly agreed social issues such as healthcare or income inequality.

I also sound like a stuck record but I think what's happening in the US under Trump at the moment will drive the majority of young people away from the Conservative movement and since conservatives are seen as religious and liberals as not I think that can only speed up the rate of religious decline in much of the US.

What really concerns me however is what happens when there's no longer enough people voting conservative to hold national power. We're already seeing different parts of the country having very different laws and I think this is both set to continue and become much more polarised.

In recent years we've seen extremist people on the right (white christian nationalists, etc) be much more likely to use violence that those on the left. If there is a big enough backlash to what the current administration is doing to keep conservatives out of many major forms of political power for some time my fear is that the more radical conservative / religious groups will withdraw into themselves and become increasingly dangerous.