The People Streaming Church Aren’t Who You Think

Education, income, and the hidden class pattern in religious attendance

I’ve been thinking a whole lot about social isolation recently. It’s probably because it’s this unspoken concept in a lot of the work that I do and many of the questions that I’m asked about religion in the United States. I swear I bring up Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone about twice a week when I’m doing interviews or giving presentations about data on religious attendance. Putnam saw an America that was rapidly hurtling toward social atomization. He charted the decline in membership in social clubs and bowling leagues.

You know what he blamed it on? Cable television. And there’s a very good reason for that—he was writing his masterpiece in the mid-1990s, when that was the major entertainment innovation. Isn’t that quaint? Now we don’t have 100 channels; we have a million channels, plus every streaming service imaginable. It’s easier to distract ourselves now than ever before.

I see church attendance as a keyhole into how people manage to socialize today. It’s one of the last voluntary social activities that Americans still do in large numbers. So the choice of whether to attend, with what frequency, and in what modality (either in person or online) is an ideal way to try to assess how the average person is thinking about “touching grass” right now.

To that end, I want to explore two factors that I think about all the time when it comes to the determinants of socialization: educational attainment and household income. I’m using the Pew Religious Landscape Study, which is exceptionally helpful here because it asks about attending religious services both in person and online.

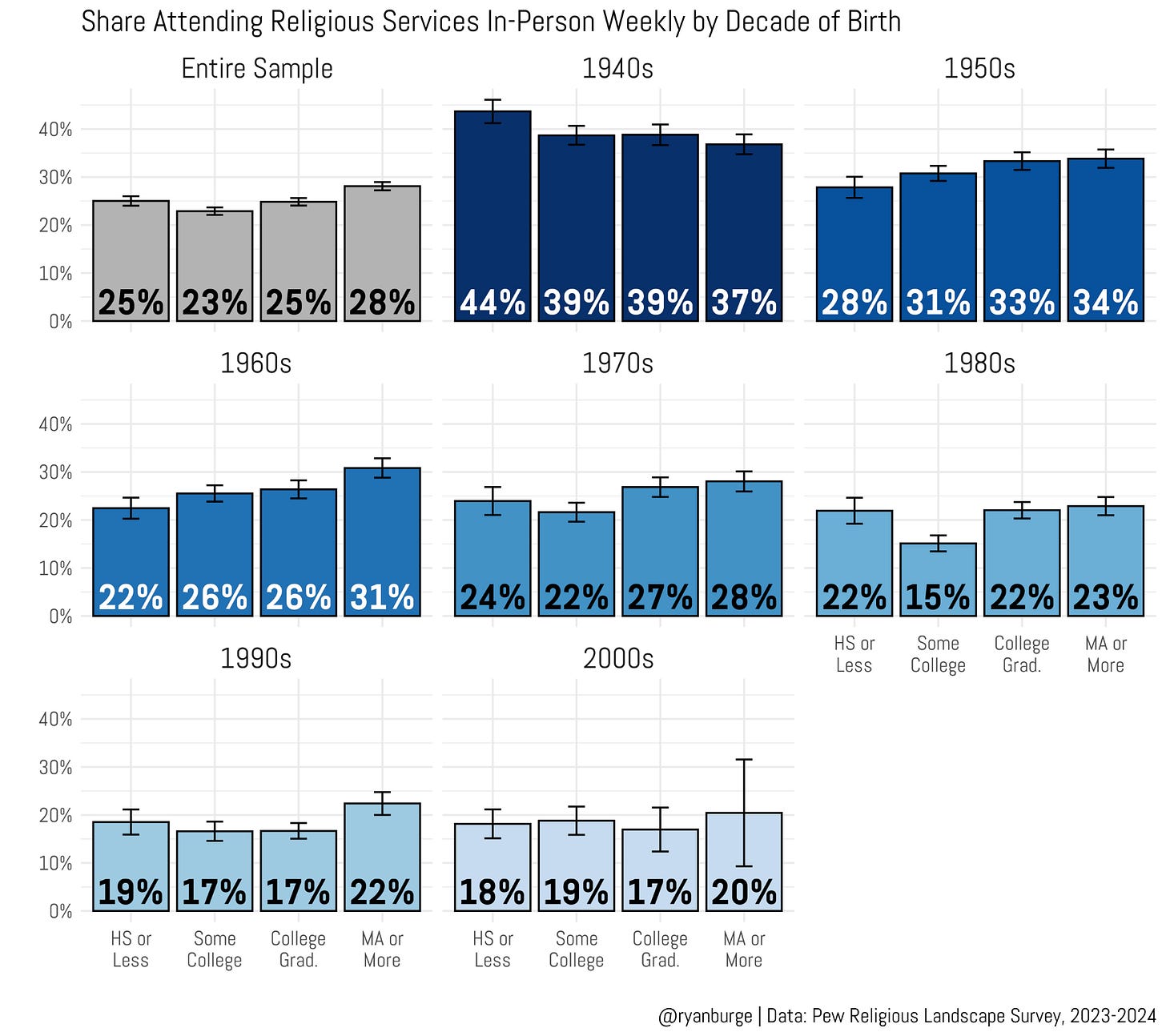

Let me start by just showing you how education interacts with in-person religious attendance across a range of birth cohorts.

The top-left graph is the entire sample thrown together—nearly 37,000 respondents. One thing you can see here is something that I write about all the time: educated people are more likely to attend a house of worship this weekend than those who have only obtained a high school diploma. The difference from the bottom of the scale to the top is three percentage points (25% → 28%), but it’s statistically significant. I will write this until I’m blue in the face: education is positively related to religious attendance in the United States.

But if you break it down by decade of birth, the patterns that emerge are a bit more nuanced. For instance, among people born in the 1940s (or earlier), it’s reversed from the overall sample. Among very old Americans, the ones who are least likely to go to church are those who stopped at high school. (For what it’s worth, I think a lot of what we “know” about social science was true for older cohorts, and we just never updated our priors.)

Look at those born in the 1950s and 1960s—there’s a positive relationship between education and attendance, and the effect is especially large for the latter group (about nine percentage points). For younger cohorts, the impact of education on increased in-person attendance is more muted, but it’s still positive in most cases. Let me state this clearly: there is no birth cohort (aside from those born before 1950) in this data where the statement, “Educated people are less religiously active,” is empirically true. Sometimes there’s no impact, but it certainly is never in the negative direction.

However, that conclusion is completely reversed when we look at the share who say that they “participated in religious services online or on TV.”