The Most Segregated Hour? Rethinking Race and Religion in America

Is racial diversity commonplace in houses of worship?

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

If I asked you to think of one quote about race and religion in the United States, I am going to bet that if you could conjure one up quickly it would be, “11:00 on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America.” It’s often attributed to Martin Luther King Jr. but in reality that statement predates King by maybe a decade or more. Regardless of who first said it, the sentiment remains the same: American religion is still one of the last spaces where one can find any sort of racial diversity.

Empirically, it’s surprisingly difficult to test because so few surveys ask about the demographic makeup of one’s congregation. I’ve rarely seen questions such as: What is the age breakdown of your congregation? Or: Do you attend with people in a similar socioeconomic situation?

But, because of the newest release of the Pew Religious Landscape Survey, we can dig more deeply into racial diversity on Sunday mornings in churches, synagogues, mosques, and other houses of worship. Lucky for us, the Association of Religion Data Archives now hosts the RLS on their website, which allows for easy exploration of variables and frequencies.

Folks were asked, “Typically when you attend religious services in person, what is the race or ethnicity of most of the other people attending?” This question was asked only of those who reported attending a house of worship at least once a year—roughly half the sample.

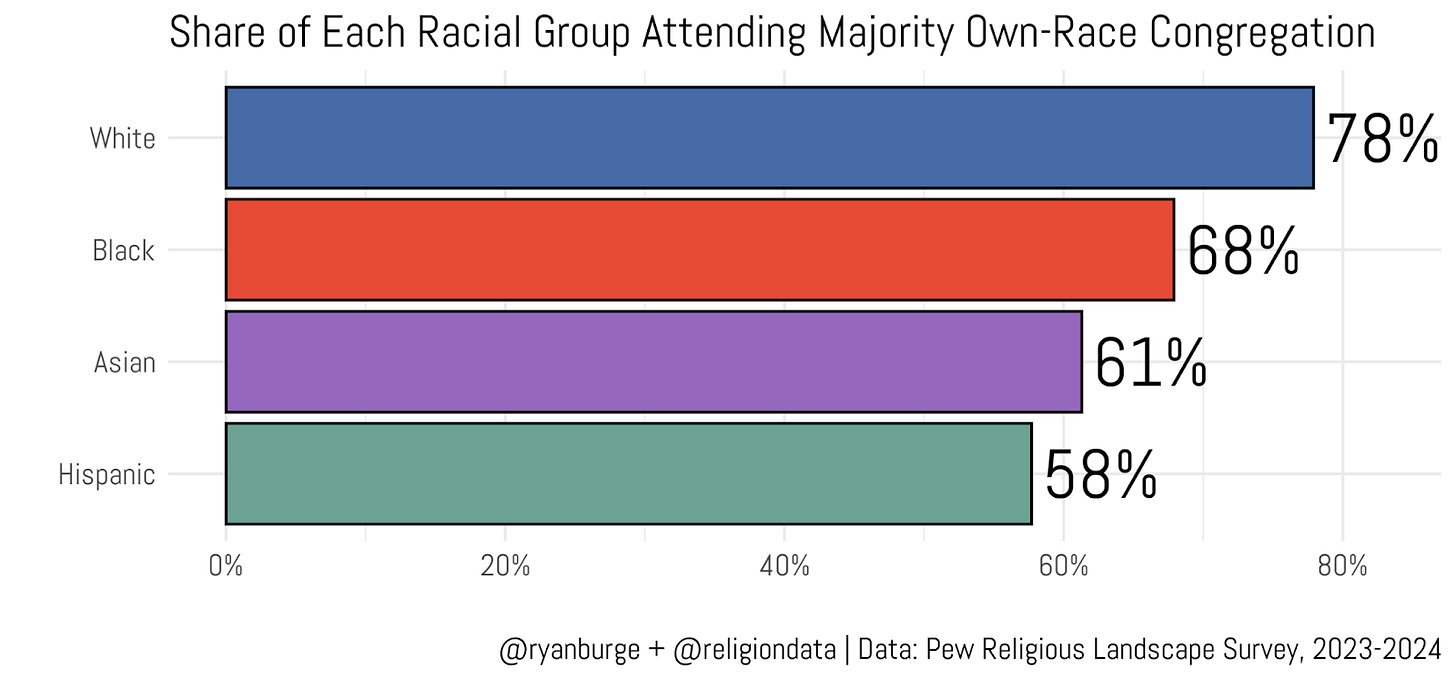

The best way to understand the responses to this question is to compare a respondent’s race to the racial makeup of their congregation. That way we can see, for example, whether a white respondent attends a majority-white church.

So, here’s what we find - most people who attend church semi-regularly worship alongside others of the same racial background. Among white churchgoers, 78% attend a majority-white congregation. For African Americans, the figure is 68%. About three in five Asians and Hispanics report worshiping in congregations where their own group forms the majority.

One thing I do want to point out here: a notable share of respondents reported attending genuinely diverse congregations — 21% said that no single racial group made up a majority. Still, the overall pattern shows people are more likely to worship alongside those of the same racial background—especially white churchgoers

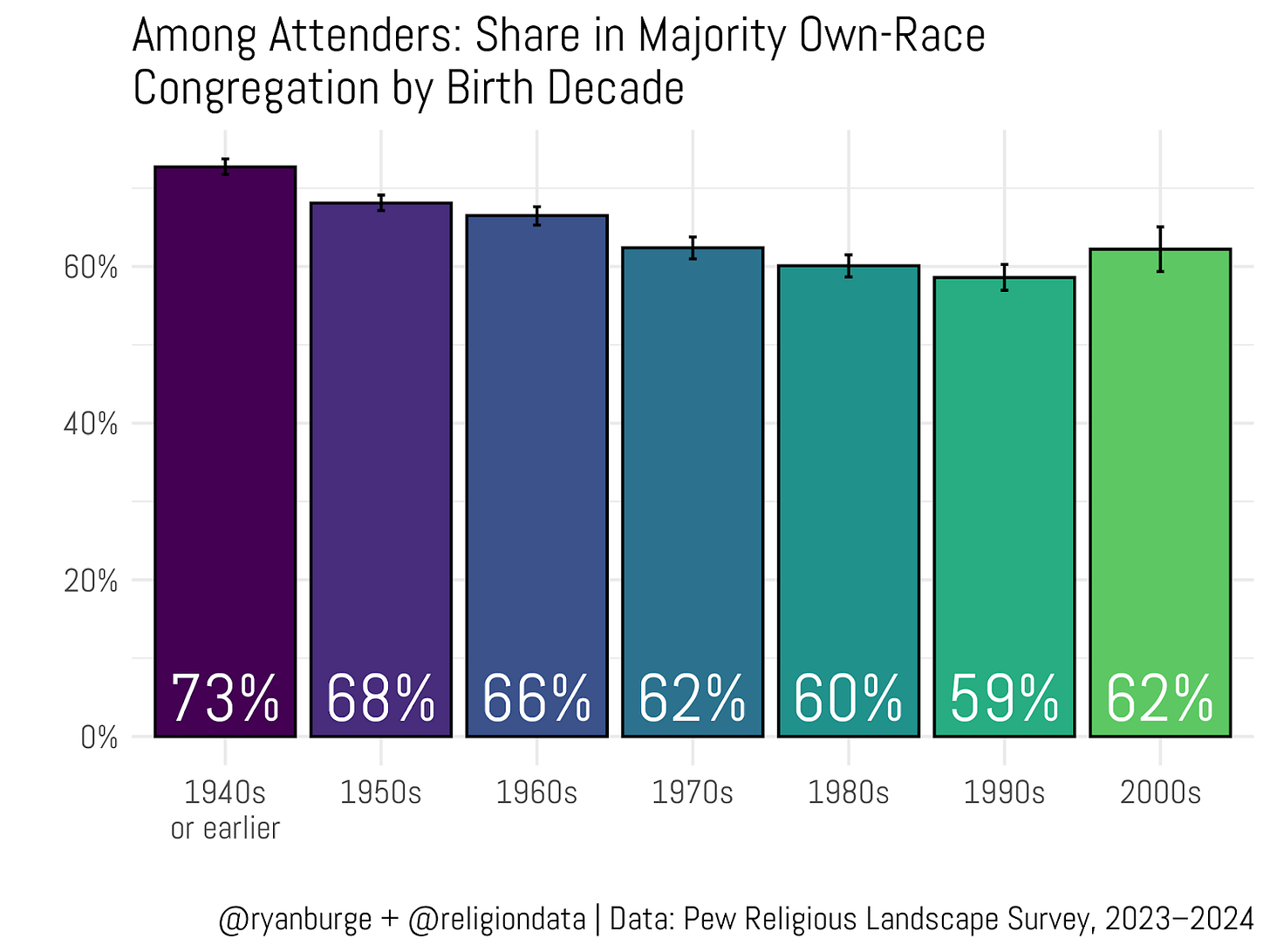

But maybe that’s changing with younger attenders compared to older ones. We know that American society is getting a lot more racially diverse with each passing year and it stands to reason that someone born in the 1990s would have had more opportunities to attend a diverse congregation than a Baby Boomer. To test that, I analyzed the data by birth decades.

Among Americans born before 1950, 73% of churchgoers attended a congregation that matched their own racial background. Younger cohorts show a noticeable decline in worshiping in racially homogeneous spaces. The shift isn’t dramatic, but it is evident: among those born in the 1960s, only two-thirds worshiped in congregations where their own group formed the majority.

This bottoms out among those born in the 1980s and 1990s at around 60%, before ticking up slightly for the youngest adults—those born in 2000 or later. Practically speaking, it seems highly unlikely that a majority of Gen Z will attend congregations that don’t match their own race. At least there’s no indication that is going to happen any time in the near future.

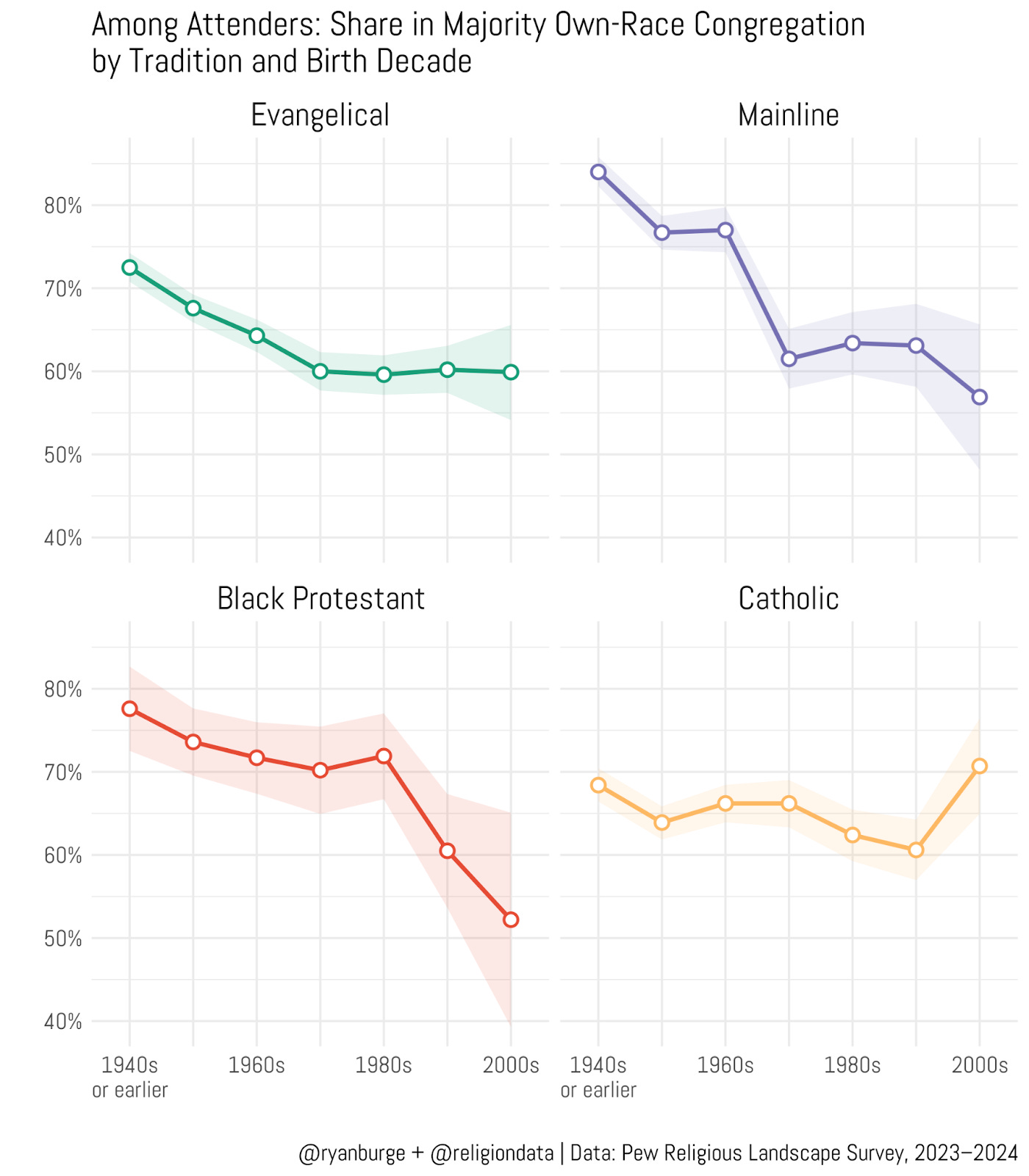

But does this pattern vary across Christian traditions? Perhaps evangelical spaces are more racially diverse than Catholic churches. It’s a question worth exploring.

About 72% of evangelicals born in the 1940s attended congregations where their race formed the majority. That share declines across successive birth decades, reaching about 60% among those born in the 1970s—and it stays there for the next few cohorts. In other words, the ‘floor’ seems to be that roughly three in five evangelicals worship in churches that match their own race.

Mainline Protestants follow a similar trajectory, though they start at a higher level than their evangelical counterparts. Among the oldest mainliners, nearly 85% worship in congregations matching their race—a reflection of how overwhelmingly white that generation is. Their numbers decline in much the same way as evangelicals, settling around 60% today.

The Catholic line tells a different story: there’s no strong trend up or down. Whether 40 or 80 years old, about 60–70% of Catholics attend congregations that match their race—suggesting Catholic churches have long been more racially diverse than Protestant ones. The one wrinkle is among the youngest Catholics: about 70% worship with co-ethnics. It’s not clear whether that’s a lasting shift or just a blip.

But does worshiping in racially diverse spaces actually shape views on diversity more broadly? Gordon Allport’s classic ‘contact theory,’ first outlined in the 1950s, suggests that it does: regular, positive interactions with people from other groups tend to reduce prejudice and foster mutual respect.

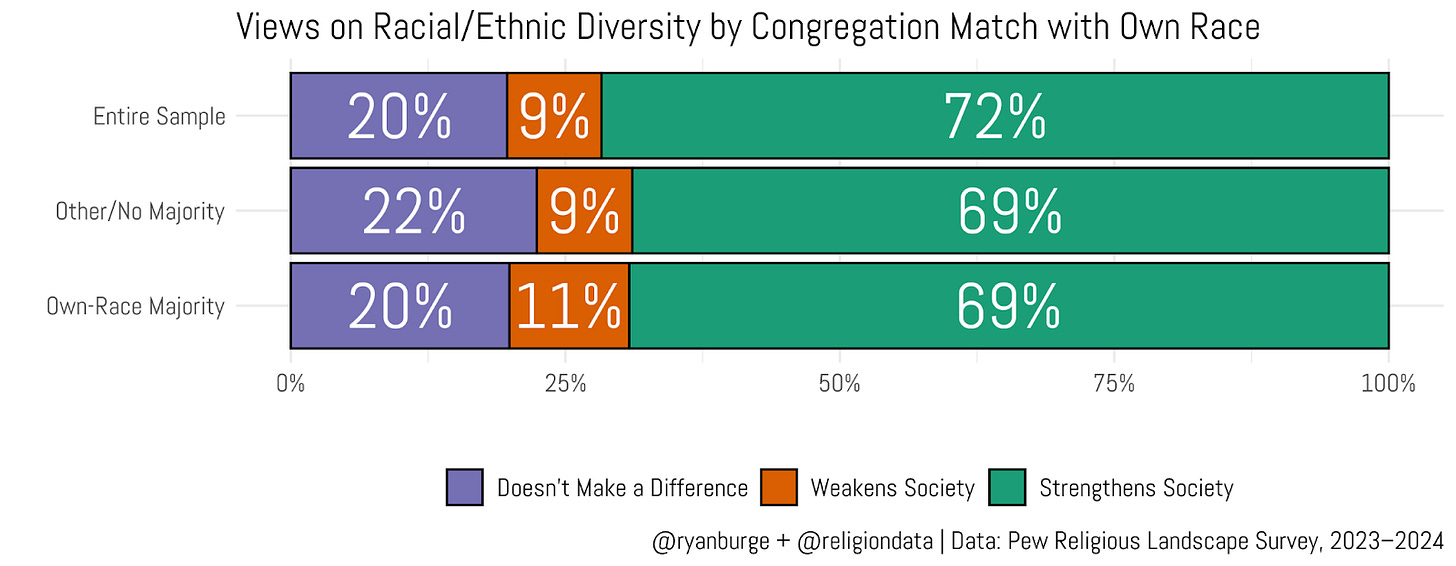

So perhaps attending a diverse congregation is linked to more openness toward immigrants and diversity. The Pew Religious Landscape Study allows us to test this. Respondents were asked: ‘In general, do you think that the U.S. population is made up of people of many different races and ethnicities…?’ The options were: it strengthens society, weakens society, or makes little difference.

I compared responses based on whether someone attended a congregation that matched their own race or one that was more diverse.

I have to admit—this graph isn’t all that striking. Across the full sample, regardless of religious attendance, a strong majority (72%) said racial diversity strengthens the country, while just 9% said it makes things worse.

When I tested whether attending a diverse congregation was linked to greater support for diversity, the results came up flat. Among those in majority same-race congregations, 69% said diversity is a strength. Among those in diverse congregations, the figure was identical: 69%

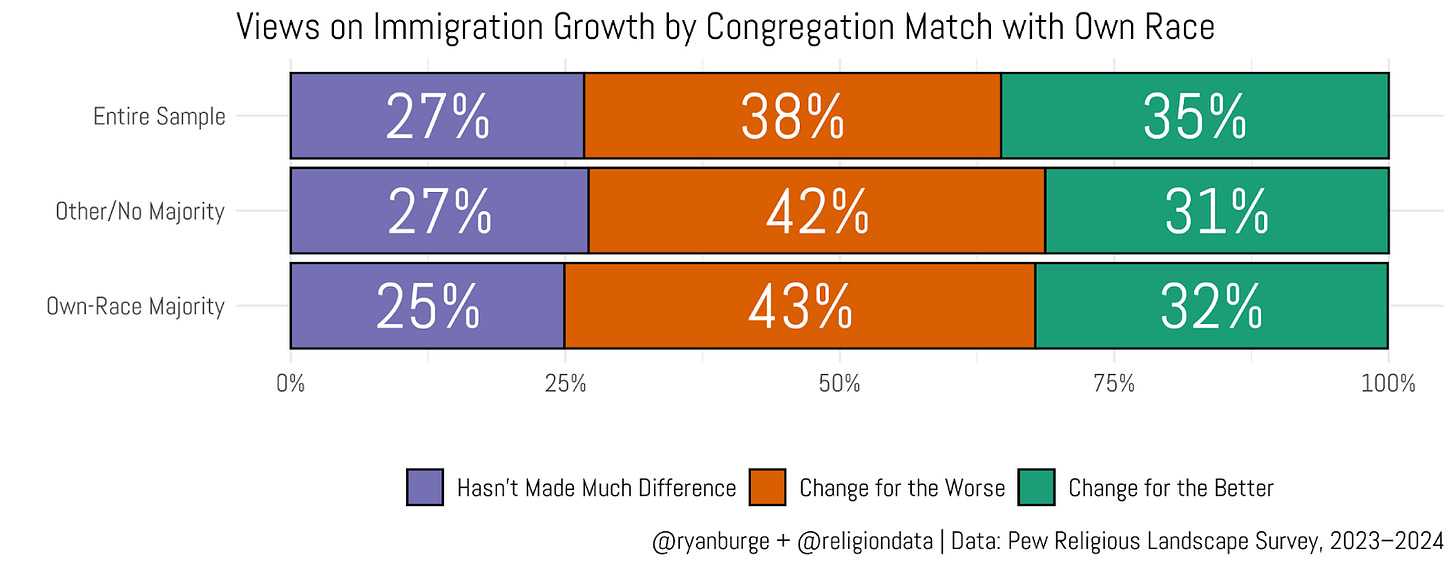

So, not much there. Let’s try a different angle. This time it was, “Thinking about changes in our society over the last 50 years, all in all, do you think a growing population of immigrants has been a change for the better, a change for the worse, or hasn't made much difference?”

Again, there’s not much to get excited about. Among those attending diverse churches, 31% said a growing immigrant population was a change for the better, while 42% said it was making things worse. For those in same-race congregations, the figures were 32% and 43%, respectively.

Those differences are neither statistically nor substantively significant. In short, there’s no evidence that worshiping alongside people of different races is associated with more permissiveness toward immigration compared to those in same-race congregations.

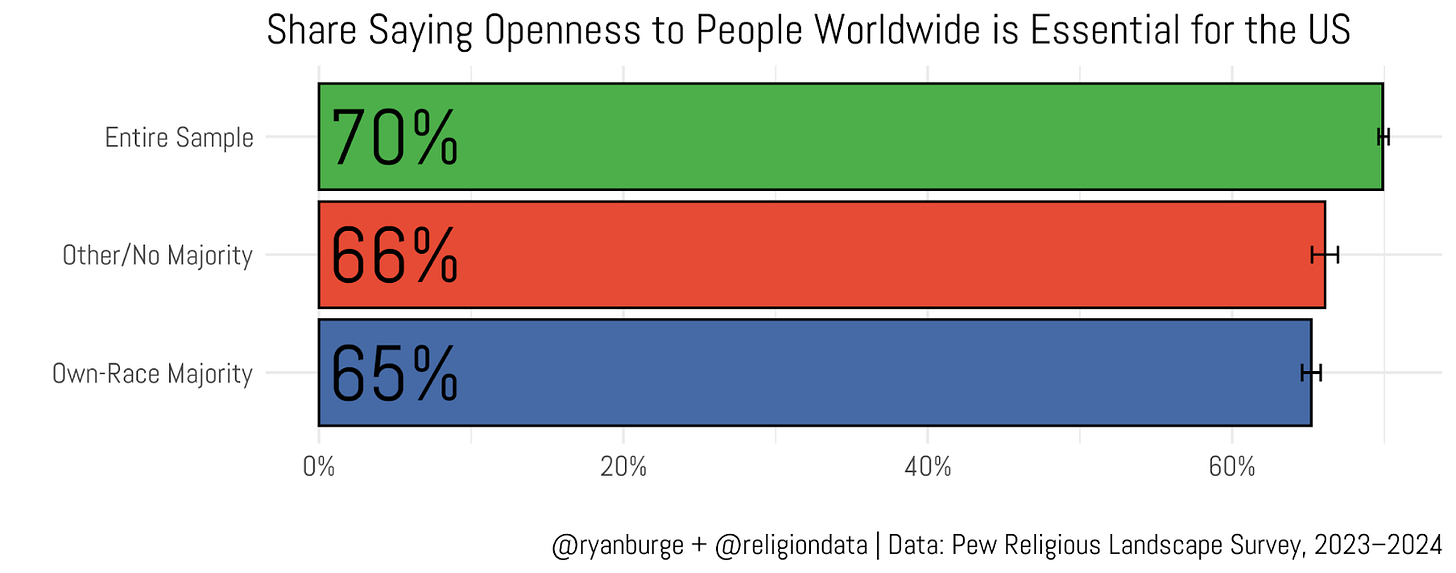

Okay, Pew had one more question in the survey that could tap into this same concept. They were asked, “Which statement comes closer to your view?”

America's openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation

or

If America is too open to people from all over the world, we risk losing our identity as a nation.

Here’s the share of respondents who chose the first option.

This seals the deal for me: there’s simply no empirical evidence that respondents in more racially diverse congregations hold views that differ in any meaningful way from those in same-race congregations. The contact hypothesis may hold in other contexts—like workplaces or schools—but it doesn’t seem to shape attitudes in the pews.

But here’s something worth noting: across the last three graphs, the ‘entire sample’ is consistently more supportive of immigration and diversity. Why? Because that group includes people who seldom or never attend religious services—and they are generally more inclusive in their outlook on America’s future.

But why does attending a racially diverse congregation not drive up support for diversity? Well, I have two possible explanations.

Social desirability bias. These questions almost invite people to give the ‘right’ answer rather than an honest one. Few want to be perceived as racist, so they default to saying, ‘diversity is good.’ It’s hard to see how survey research will ever fully overcome this.

It may be a case of endogeneity. People already open to diversity are more likely to seek out racially heterogeneous congregations. In that case, it’s not the congregation shaping their opinions, but preexisting beliefs driving their choice of where to worship.

I should highlight Hahrie Han’s recent book Undivided: The Quest for Racial Solidarity in an American Church. Focusing on a majority-white congregation grappling with race, it vividly shows just how difficult these conversations can be.

So is 11 a.m. still the most segregated hour? Maybe. But the data suggests congregations are slowly becoming more diverse with each passing year.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

Another triumph of the Null Hypothesis (with a "maybe" level of confidence).

Why is racial diversity in each congregation a goal? Many/most churches are neighborhood churches, so that's one factor that this article didn't discuss. Then there are styles of worship, from drums and guitars to liturgical/classical music, and that might be correlated with race. Isn't it more important that the church overall help all kinds of people in all their preferred, effective style of worship rather than making each parish statistically diverse? Shouldn't God somehow come into the picture?