How Big is the God Gap on College Campuses?

New data from over 68,000 college students reveals how faith still shapes political identity

Central Indiana Friends! I will be driving through your area on Sunday, March 1st on the way to Oxford, Ohio for an engagement o the evening of March 2nd. I would love to speak at an event in your area for a reduced rate. It could be a church, community group, etc.

If you are interested, just fill out this form and I will be in contact.

It’s the most important feature of American religion and politics that I wish more people understood: the God Gap. Simply put, religious people tend to gravitate toward a conservative political ideology and tend to favor the Republican Party on election day. Among the non-religious, it’s just the opposite — they are more apt to say that they are politically liberal and that they align with the Democratic Party.

But I wanted to try and figure out if that gap may begin to narrow or if it will widen in the future by using a new dataset I’ve gotten my hands on from FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), which is doing a really great annual poll of college students. The total sample size is 68,510 students attending 257 universities across the United States. It’s not a representative sample of all college students, but it is definitely in the ballpark of a solid sample.

There are two questions about religion in the survey: affiliation and attendance. That means I have more than enough to start poking around on the God Gap.

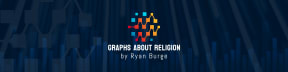

Let me start by showing you the distribution of political ideology based on self-reported levels of religious attendance.

And, boy, that is a beautiful cascade of stacked bars. Among college students who report that they never attend religious services, 33% report that they are “very liberal,” and nearly the same share (32%) indicate that they are “somewhat liberal.” If you throw in the “slightly liberal” portion, you get two-thirds of never attenders on the liberal side of the spectrum. In contrast, conservatives make up 10% of the never attenders.

As attendance goes up, the liberal share goes down and the conservative responses begin to rise. The liberal share drops below 50% of the sample when you get to attendance that’s once a month or more. But here’s a fun fact — the only attendance level where conservatives make up a majority is among those who attend a house of worship multiple times per week. Those folks make up 3% of the sample. Meanwhile, the never attenders are ten times that large (32%, to be exact).

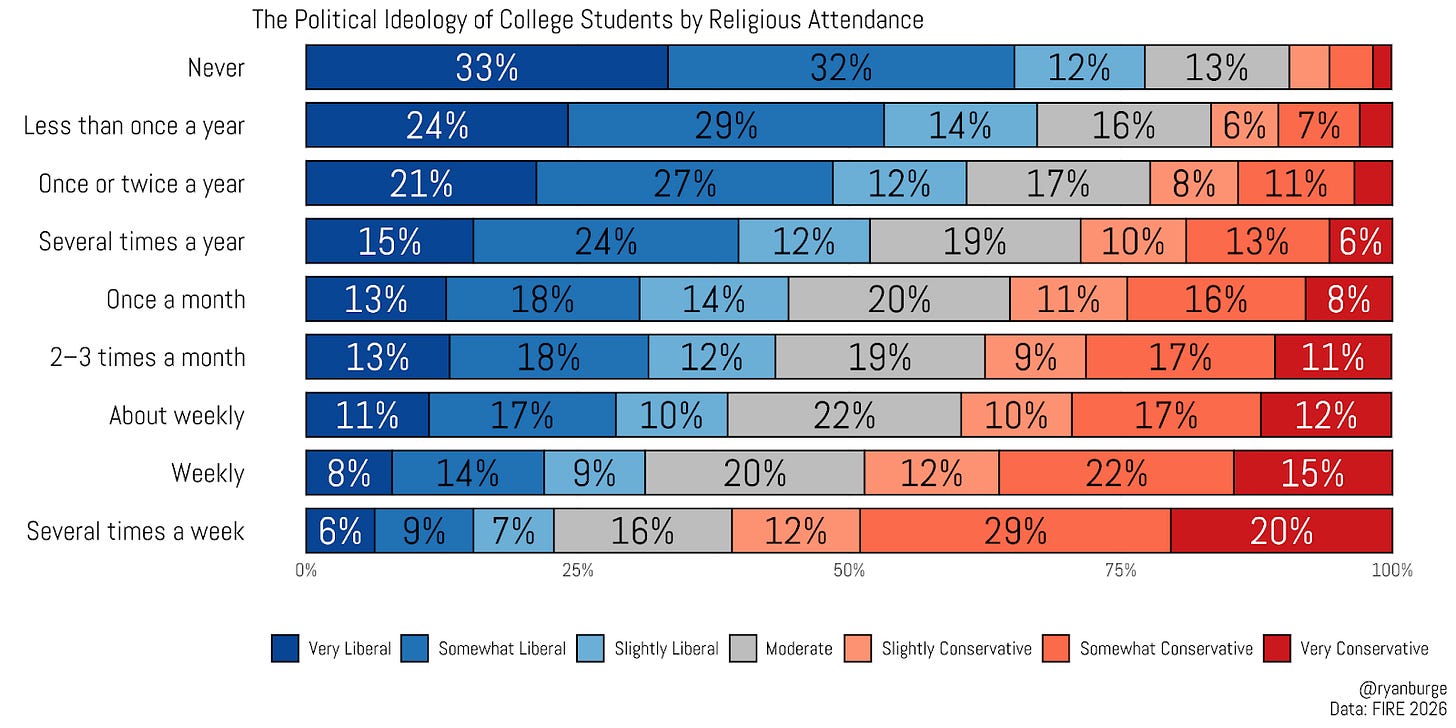

So, as attendance rises, liberalism drops. Let me show you the same question, but this time I will break it down by religious affiliation.

There is clearly one group that stands out from all the rest — Latter-day Saints. Among the LDS in the sample, 53% of them describe their political ideology as conservative. No other group comes even close. What also jumps out to me is that the other Christian groups in the sample look almost exactly the same. The share who are conservative is right around 40%; the share who are liberal is nearly the same. The last 20% say that they are politically moderate. So, in other words, Christians are really purple. That’s an idea that I’m going to return to a bit later.

Now, there are a bunch of traditions where liberals are the majority. They include Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, atheists, agnostics, and “nothings in particular,” too. The group that is the most left-leaning is atheists. A whopping 84% of them say they are liberal — two points higher than agnostics and twelve points higher than “nothings in particular.” It’s also worth pointing out that Jews, Buddhists, and Hindus look pretty similar on this metric, too. Muslims are about ten points less likely to be liberal than those other groups.

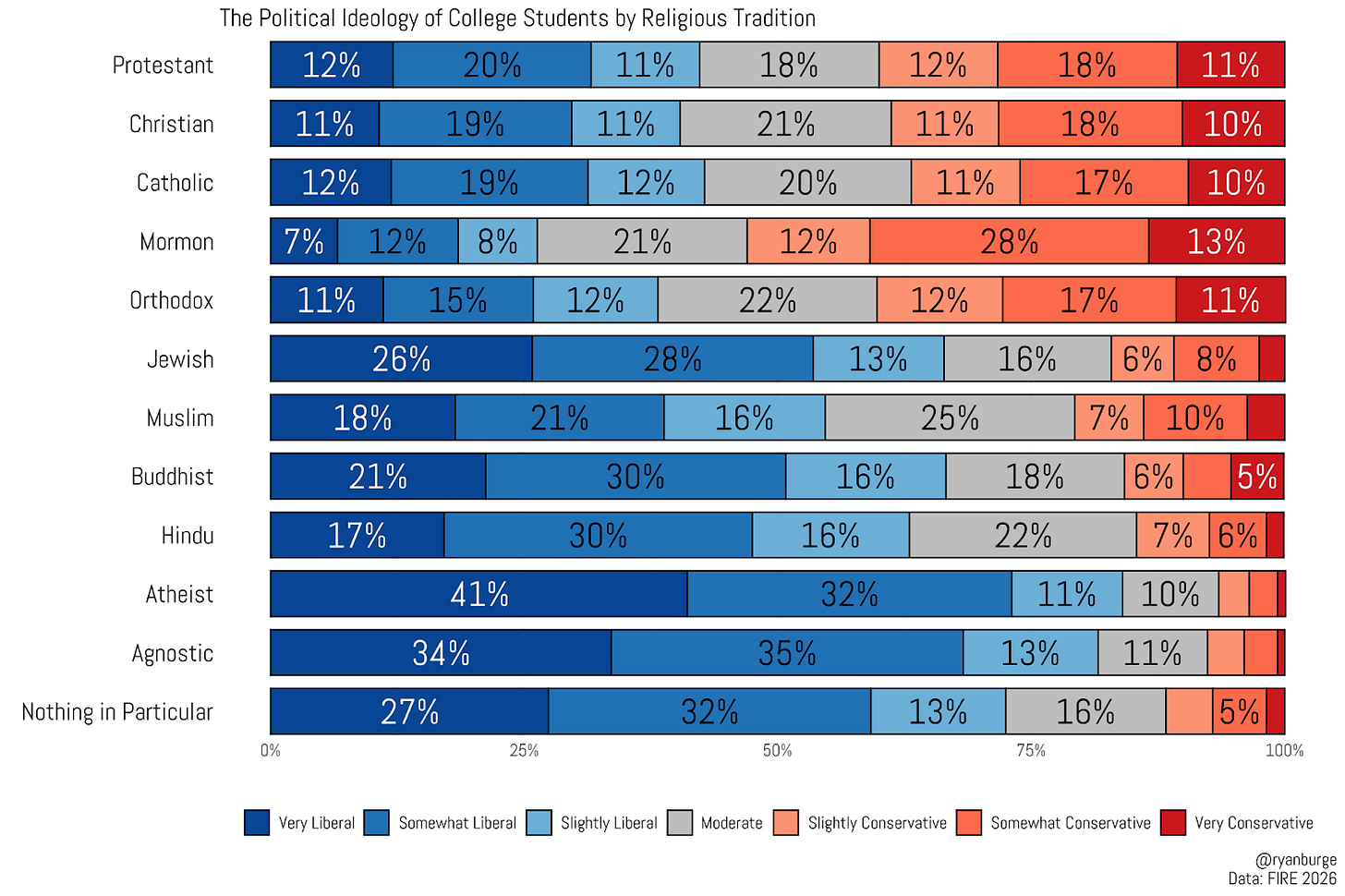

Let me add another dimension to this analysis by throwing in political partisanship, too. I am mapping the mean score for each tradition on two axes — ideology is on the horizontal axis, and partisanship is on the vertical. The size of the points indicates the sample size.

It’s pretty neat how these points fall on a fairly straight line that runs diagonally through the plot. It should come as no surprise that liberals tend to lean toward the Democratic Party, while conservatives go the other direction. It’s also pretty striking how the three broad groups of religious affiliation (Christians, world religions, and the nones) all line up in a fairly consistent order.

In the top right, you have Latter-day Saints. They are easily the most conservative and the most Republican religious group. Then there’s a pretty big gap until you find the rest of the Christian groups. Note how closely clustered they are, too. In fact, there’s essentially no difference between Catholics, Protestants, Christians, and Orthodox Christians. They sit right in the middle of both the ideological and partisan continua.

Then you have the world religions, which are fairly clustered together, too. They average a score of 3 out of 7 on both ideology and partisanship. I do think it’s fair to say that Muslim college students tend to be a bit more centrist than Buddhists, Hindus, or Jews. However, the gap is not huge.

Then you have the three types of nones in the bottom left corner. You can see that there’s a pretty clear order, though: atheists are the most left-leaning, followed by agnostics and then the “nothings in particular.” That really tells you a lot about the God Gap in American politics in a single graph. The chasm between the red circles and blue ones is what the political future of the country looks like.

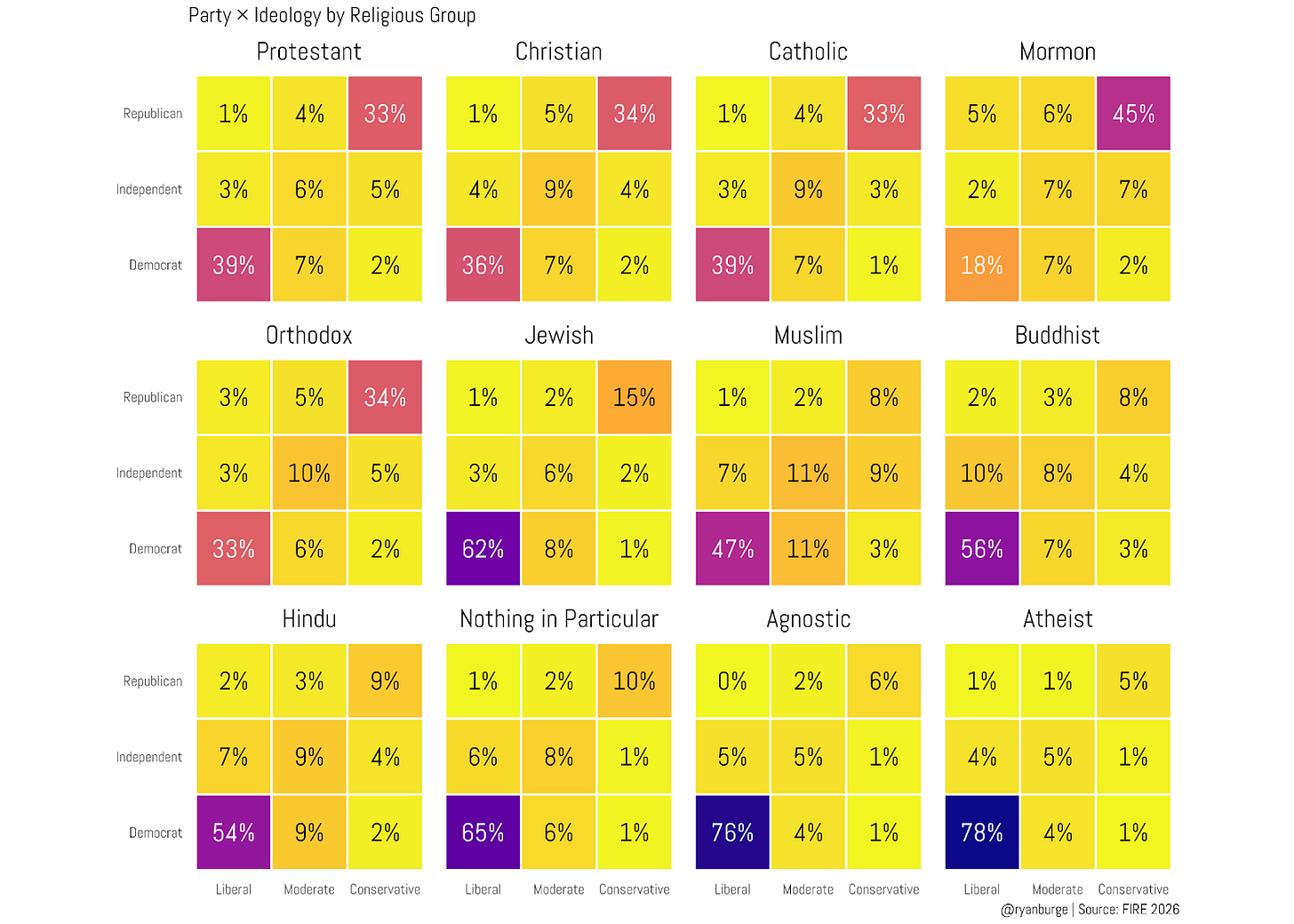

Let me visualize this in a couple of heatmaps, too. I collapsed the seven-point scales into three-point scales on both partisanship and ideology and calculated the distribution of the twelve religious groups across these nine squares.

I want you to take note of something across the top row. Can you see where the largest concentrations of college students are? The top right (conservative Republicans) and the bottom left (liberal Democrats). But in the biggest traditions, those numbers are pretty much the same. It’s like Protestants and Catholics are clustered at the two ends of the political and ideological spectrum.

That’s not true for the rest of the sample found in the last two rows. For instance, 62% of Jews are liberal Democrats. It’s 47% of Muslims, 56% of Buddhists, and 54% of Hindus. The same pattern is there for the non-religious as well. Consider this: over three-quarters of atheist and agnostic college students say that they are liberal Democrats. There’s no bimodality there — they are grouped around a single part of the ideological and partisan spectrum.

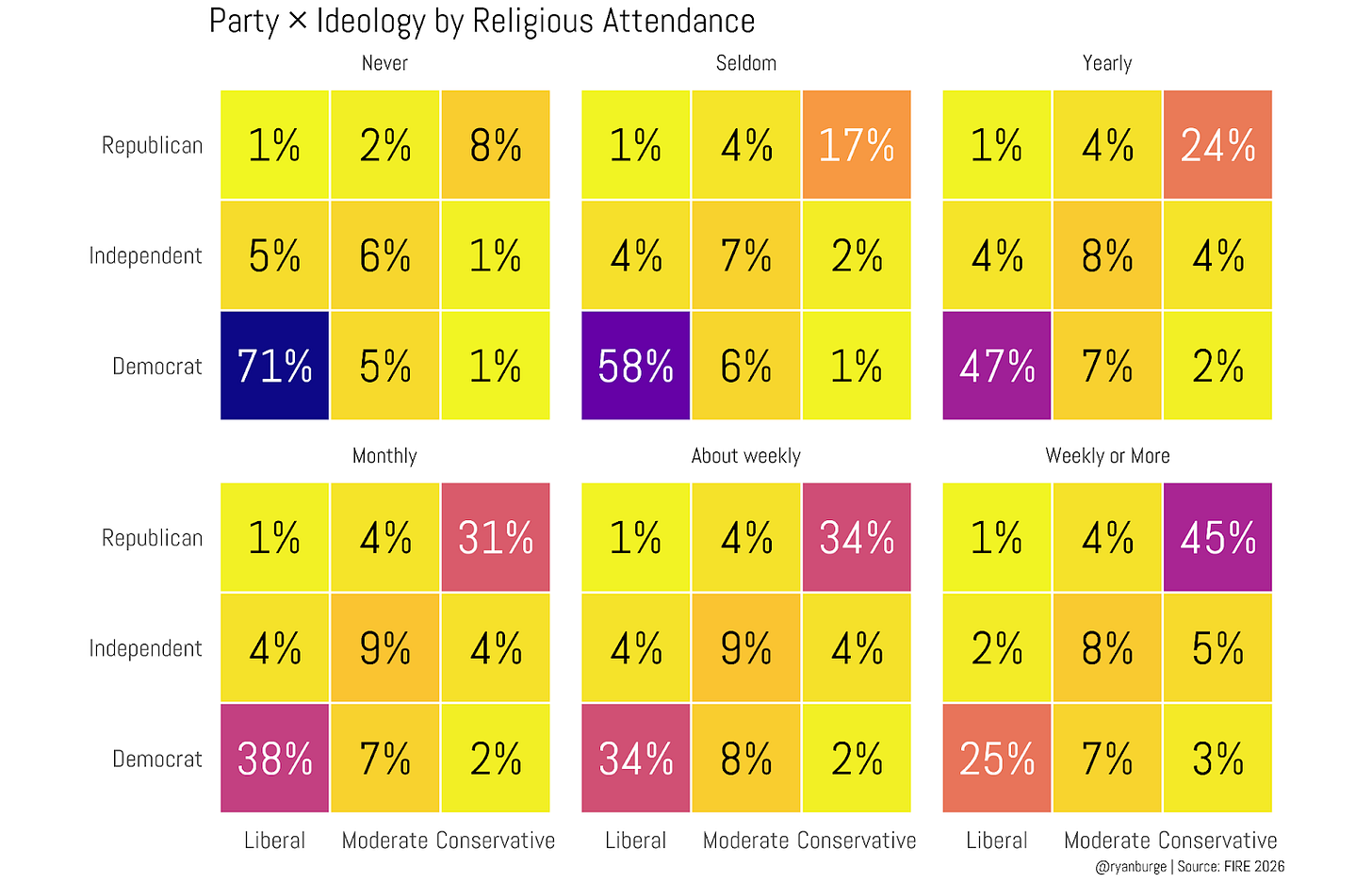

Doing the same analysis by level of religious attendance is also illuminating.

Given what we observed in the prior heatmap, it should come as no surprise that the level of attendance that was the most politically unified was the never attenders — 71% are liberal Democrats. Meanwhile, just 8% are conservative Republicans. That’s a gap of 63 points. I think that’s a pretty good metric to calculate political homogeneity among these attendance categories.

For seldom attenders, the gap is 41 points. It drops to 23 points among yearly attenders, and it’s only 7 points for those who report monthly attendance. Then look at the weekly attenders: 34% are conservative Republicans, and exactly the same percentage are liberal Democrats. But among folks who attend at least once a week, it flips the other direction — 45% are conservative Republicans and 25% are liberal Democrats.

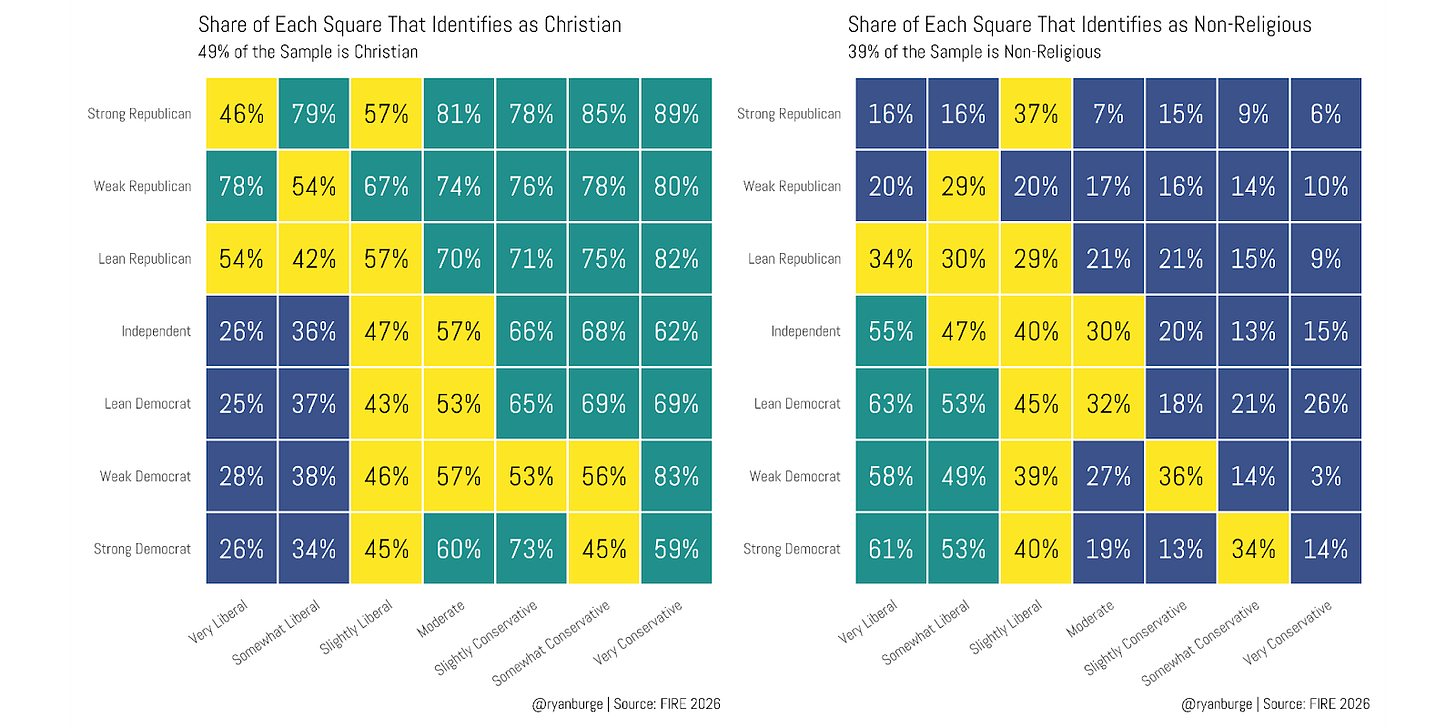

I wanted to try to visualize where Christians are over represented across the seven levels of ideology and partisanship, so I calculated the share of Christians who could be found in each square. Then I did the same for the non-religious. The way you can read this is pretty straightforward: green squares are places where a group is over represented, and blue squares are where they are underrepresented.

In the full sample, about 49% of all respondents said that they were Christians. Where do they show up the most on the heatmap? It’s the top right corner — that’s the square that is ideologically conservative and Republican. Where are they more rare? The bottom left — that’s folks who are liberal Democrats.

And guess what the graph of the non-religious shows? The exact opposite of that. The nones can be found in large measure in the left-leaning part of the heatmap. For instance, while the nones made up 39% of the entire sample, among very liberal strong Democrats, 61% of them said that they were atheist, agnostic, or had no religion in particular. In contrast, just 6% of very conservative strong Republicans were nones.

This is a real representation of how religious groups “live” in different parts of the political and ideological spectrum.

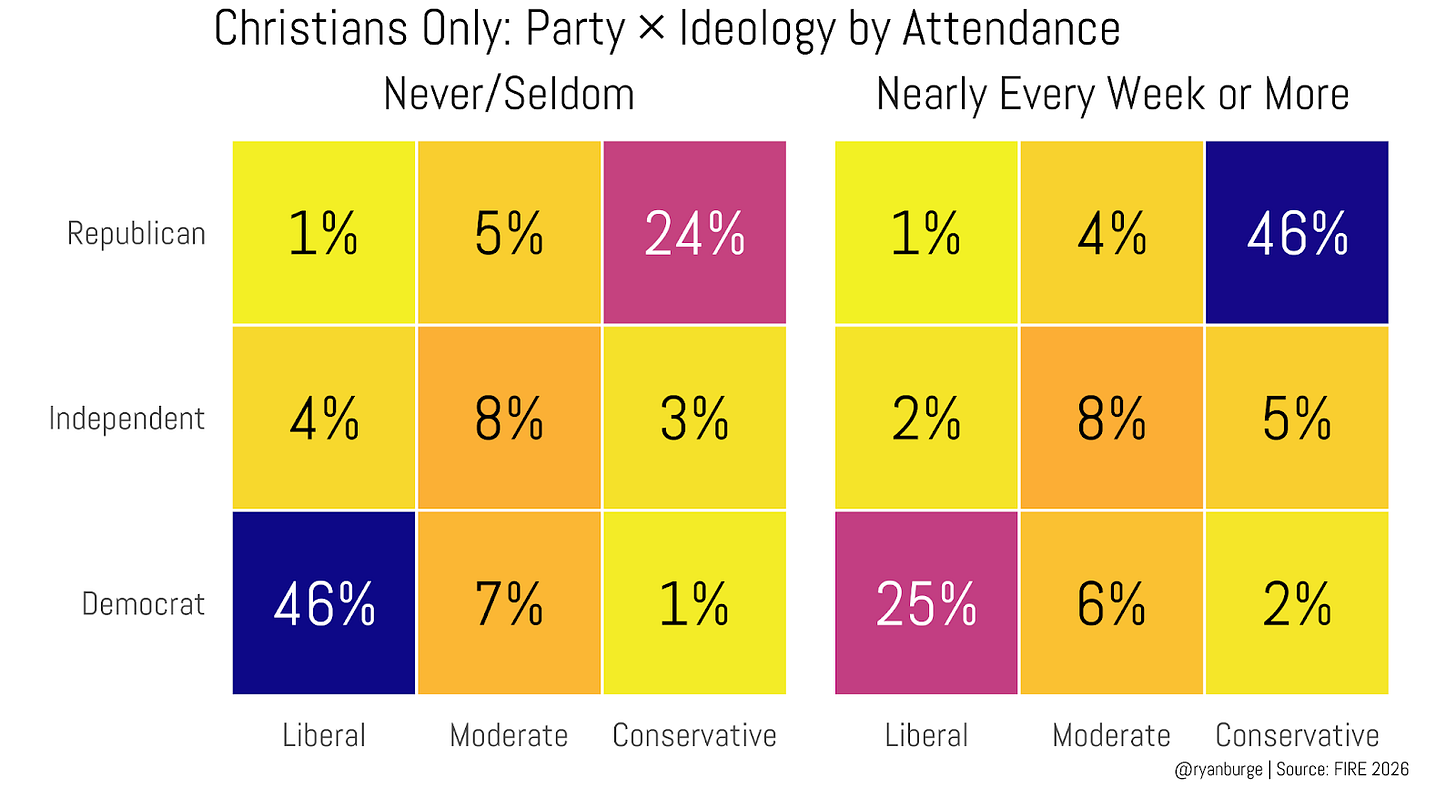

But one more thing before I go. You know how the Christian groups above were the most politically divided? For instance, among Protestants, 39% were liberal Democrats and 33% were conservative Republicans. That’s a pretty good balance, right? I wanted to pull back the curtain on that just a bit by dividing the sample into the low-attending Christians and those who attend nearly every week or more.

And these graphs are basically the opposite of each other, right? Among the never/seldom-attending Christians, 46% are liberal Democrats and 24% are conservative Republicans. For those who go to church on a weekly basis, 46% are conservative Republicans and 25% are liberal Democrats. Do you see why the numbers above were so even? The heatmap on the left balances the heatmap on the right when you look at the numbers in the aggregate.

There’s a lot going on here, so let me summarize:

Among Christians, their politics are divided between left and right. For most groups, the share of liberal Democrats is nearly the same as the portion who are conservative Republicans.

The non-religious are much more politically homogeneous. About three-quarters of atheists and agnostics indicate that they are liberal Democrats.

But the political divide among Christians is really a chasm between the active and inactive groups. For those who don’t go to church that much, they are 20 points more likely to be a liberal Democrat than a conservative Republican. Among the weekly attenders, it’s exactly the opposite.

That data does indicate that even low-attending Christian college students are less liberal than atheists, but the real difference is between the Protestants and Catholics who go to church weekly and the non-religious.

The FIRE survey asks a bunch of questions that try to understand whether these students are “self-censoring” on sensitive topics. So expect to see more on this data in the near future.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

"Simply put, religious people tend to gravitate toward a conservative political ideology and tend to favor the Republican Party on election day." Alternative wording: Religious people tend to choose doctrinally conservative (often ancient) forms of faith -- Christian and Jewish -- and, thus, tend to vote against political leaders who advocate cultural and moral policies that clash with their beliefs (including a traditionally liberal approach to the First Amendment, affecting freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of religious practice).

I appreciate the thoughtful analysis and your willingness to look for what data is available and study it. I do regret the lack of interest in surveying the majority of young people in that age group who are not college students. I would think there might be substantial differences between college and working class young adults.