Higher Education on Trial: Religion, Politics, and Public Doubt

The Great College Confidence Collapse

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

I think it’s more than fair to say that we are not in the ‘golden age’ of American higher education right now. The Trump administration has supported a budget plan that would cut at least $160 billion of funding to colleges and universities across the United States. Dozens of universities have been directly impacted by a reduction in funding for NIH grants, leading to massive layoffs. The White House has also escalated a conflict with Harvard University which began with cutting $2.4 billion in grant funding and has introduced a new directive that Harvard can no longer enroll international students, which make up about 20% of their student population.

But it’s not just the current political climate that is creating headwinds in higher education. Colleges and universities are bracing for a demographic cliff over the next five years, driven by a sharp drop in birth rates during the Great Recession. The end result is a dramatically smaller pool of potential incoming freshmen in the near future. What compounds this is the fact that confidence in higher education has declined precipitously in the last ten years. Gallup data shows that confidence in higher education declined from 57% in 2015 to just 36% in 2024.

However, what role does religion play in this changing perception of higher education in the United States? There’s long been a discourse in the literature about how certain faith traditions seem to discourage advanced education. This is typified in Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life and Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. But, some new data from PRRI may provide a lot more nuance to this conversation.

The ARDA hosts the American Values Survey, which was fielded in August of 2023. They asked respondents, “Today, would you say that a college education is a smart investment in the future or is it more of a gamble that may not pay off in the end?”

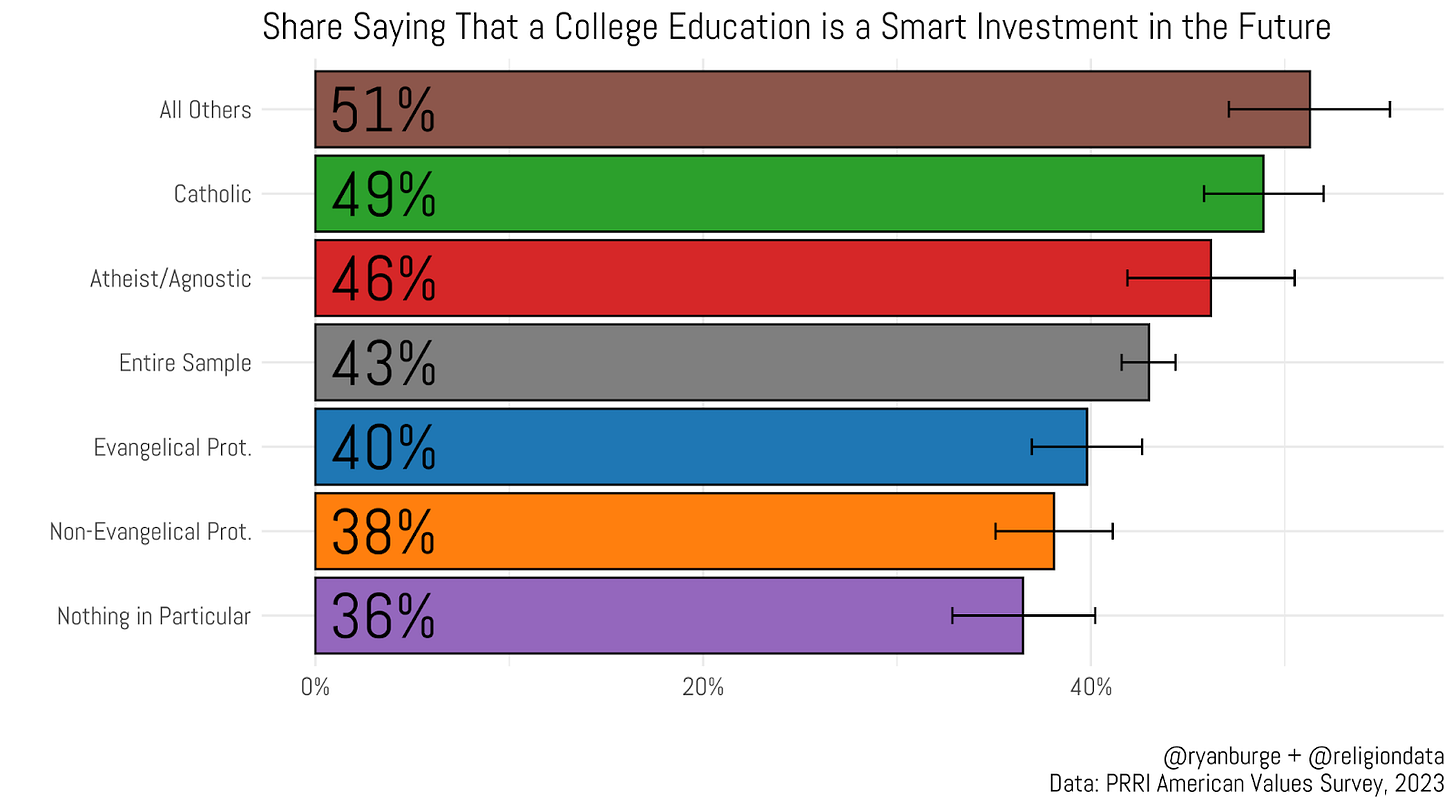

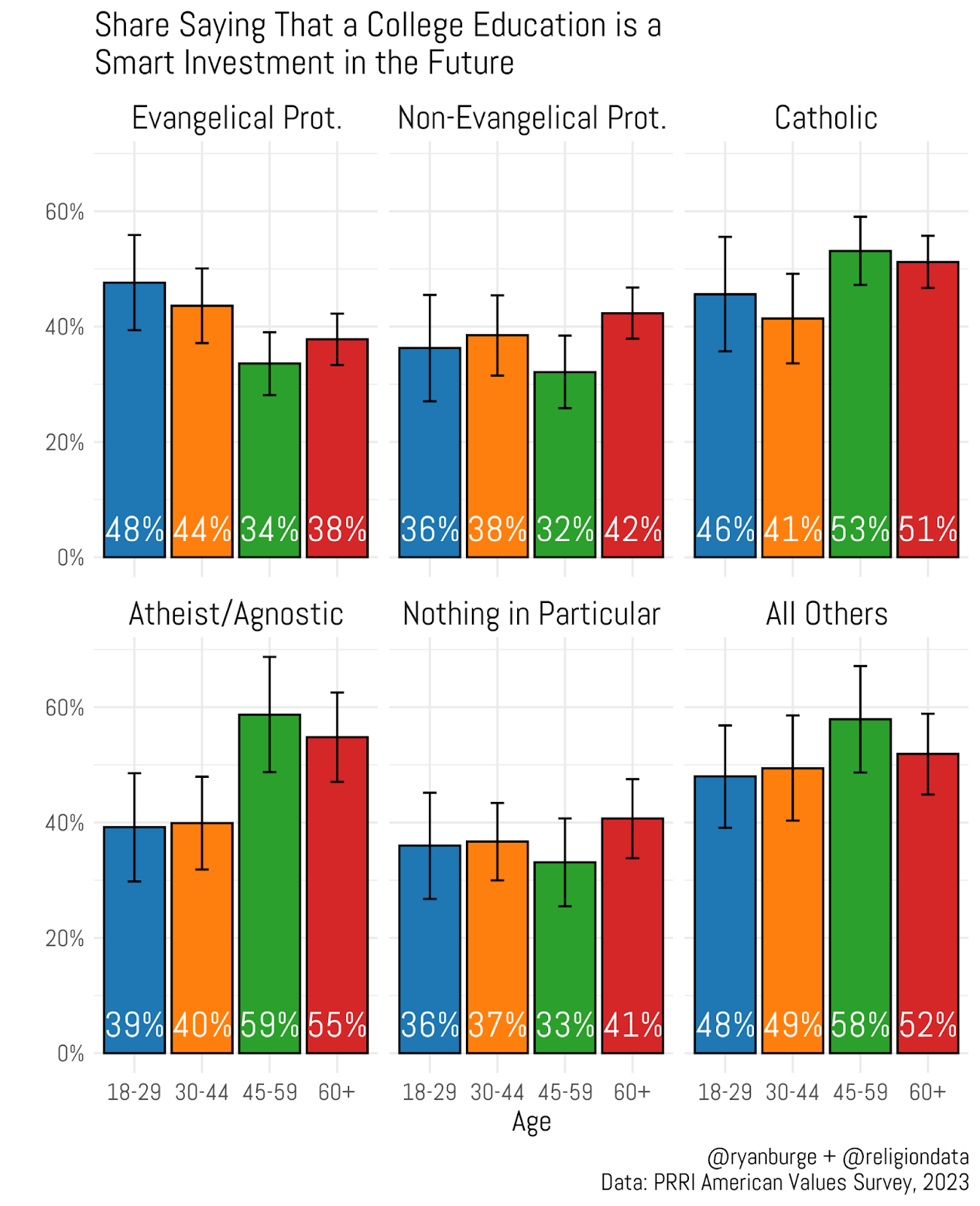

In the entire sample of about 2,500 respondents, only 43% of them said that it was a smart investment in the future. That’s pretty stunning to think about - most Americans did not believe that earning a college degree is worth the time and money involved. When I broke it down by religious tradition, there was some significant variation between groups. For instance, only 36% of people who claimed ‘no religion in particular’ saw college as a good choice. For atheists/agnostics it was ten points higher than that.

Among Christian groups, Catholics were clearly the most supportive of higher education but even they were evenly divided on its utility. Interestingly, evangelical and non-evangelical Protestants expressed nearly identical views on this question. The most supportive group was a category that included smaller religious traditions such as Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus. This likely reflects the high educational attainment found in many of these communities, which is something I write about extensively in The American Religious Landscape.

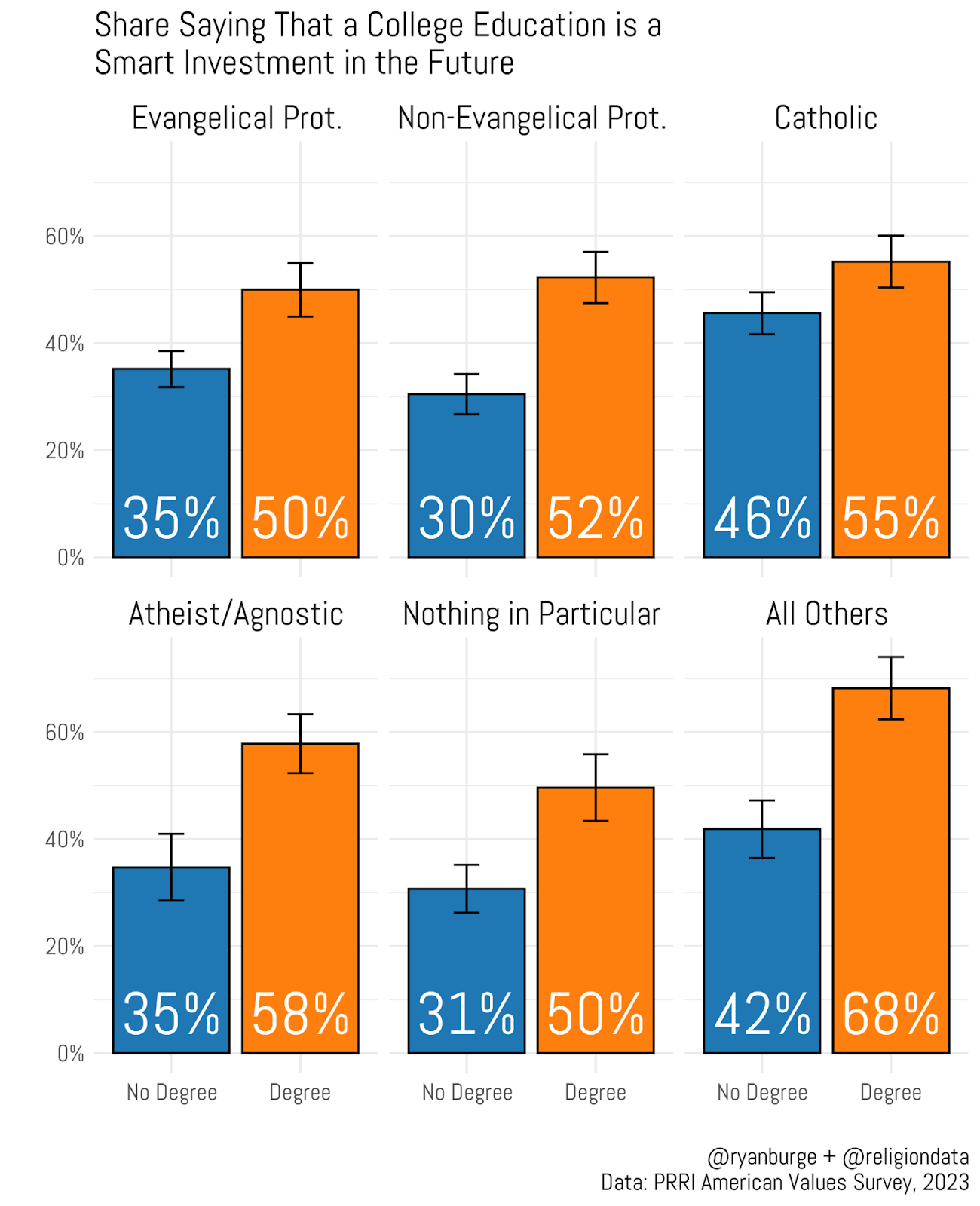

But, I can test that more directly by just dividing the sample into those who have earned a four year college degree and those who have not.

It's not surprising that those with college degrees are much more apt to say that going to college was a smart investment for them. For both types of Protestants about half of the degree holders see higher education as a good option, compared to only about a third of Protestants who did not complete a four year degree. But there’s another way to look at this - about half of people with a bachelor’s degree don’t think it was a smart investment. That’s a sobering statistic.

That same education gap is there across all the religious traditions, but it’s the smallest among Catholics. Even among those without a degree, 46% say that college is a good choice compared to 55% of Catholics who finished college. The two groups with the biggest gaps are atheists and agnostics at 23 percentage points and the ‘all others’ category at 24 points. My prior hunch is confirmed here: highly educated Jews, Muslims, and Hindus see a tremendous value in earning a college diploma.

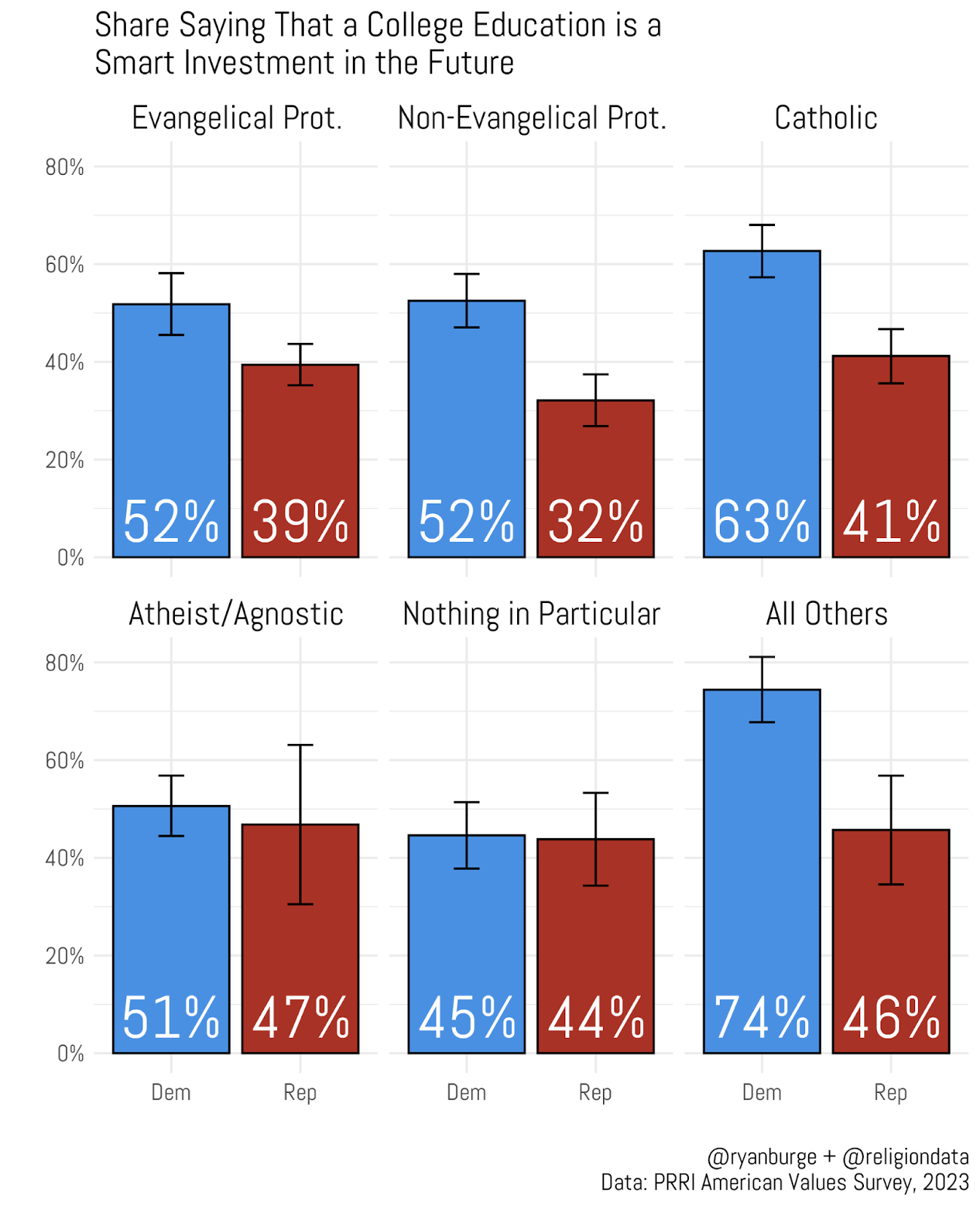

Another variable worth exploring is political partisanship. Pew found that Republicans were about forty points more likely to have a negative view of higher education than Democrats back in 2019. Is the partisanship gap in these results, too?

The answer is a qualified “yes.” For the top row of results for Protestants and Catholics, there is a big difference between Democrats and Republicans. The data consistently finds that Democrats have a more positive view of higher education and that gap is often large. It’s twenty points for non-evangelical Protestants and twenty-two points for Catholics. Republican Christians are not huge fans of higher education.

But when we look at the non-religious, the results indicate that partisanship doesn’t matter at all. While there aren’t a whole lot of Republican atheist/agnostics, their view of higher education is about the same as Democrats. The same is true for nothing in particulars, as well. We do see a big gap among the ‘all others’ group - with almost three quarters of Democrats saying that higher education is a good investment. That’s 28 points higher than Republicans in this religious category.

There’s another factor that may be at play, too: age. Maybe older people who grew up in a time when getting a college degree was pretty rare just don’t value going to college. In contrast, younger people are growing up in an information economy and believe that the only way to move up the economic ladder is by graduating from college. That’s what Pew found, by the way, in 2024 - young people were more convinced of the necessity of a bachelor’s degree.

The graph for evangelical Protestants really jumped off the screen for me. Among those in the youngest age categories, there’s clearly a more positive perception of college. About 45% think that getting a degree is a smart investment. It’s ten points lower for older evangelicals in this sample. What’s interesting about Catholics is that this relationship may be reversed - older Catholics are more positively inclined toward higher education. But the sample size is too small to know for certain.

The other big finding for me is among atheists and agnostics. It’s readily apparent that the older set are much more inclined toward education than younger secular Americans. This gap is not small, either. It's at least fifteen percentage points. I really don’t have a great answer for this, for what it’s worth. But I can say this - young atheists and agnostics are certainly not huge champions of going to college.

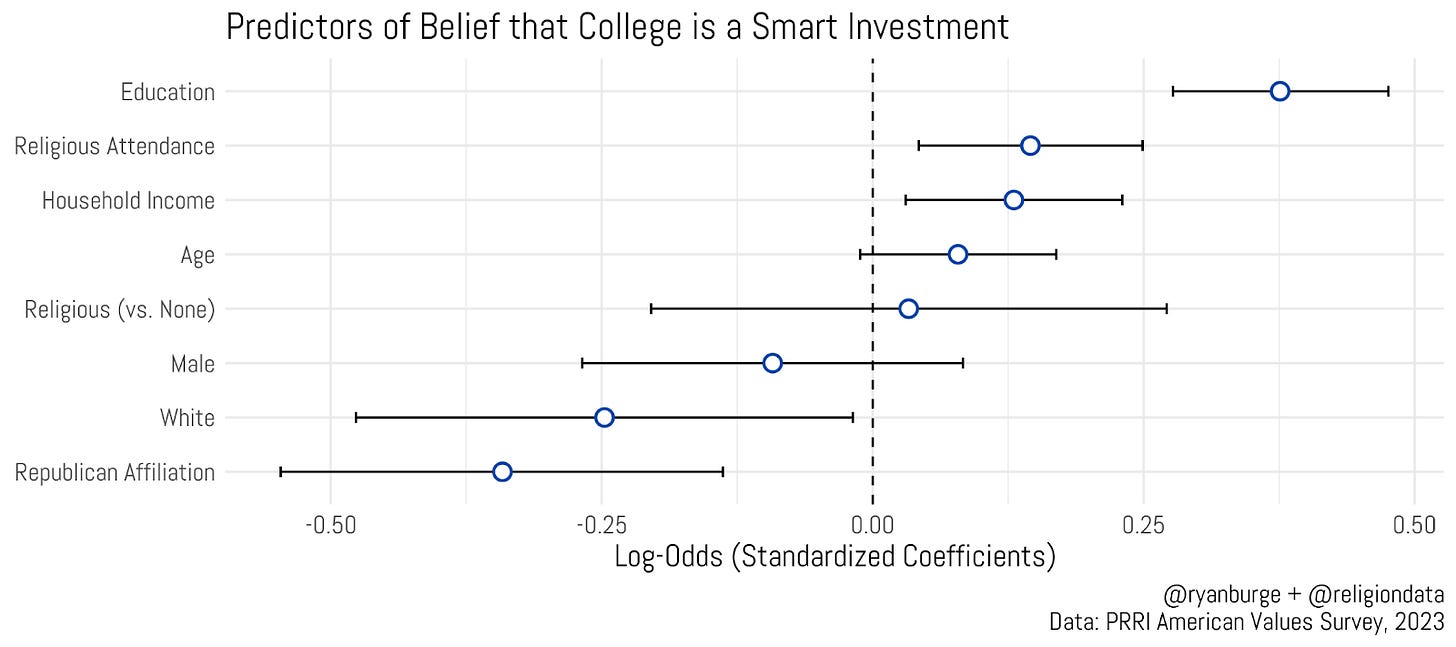

What emerges so far is a pretty mixed picture of results. Are religious people more inclined toward education or does something about affiliation or attendance make an individual less apt to seek out a college degree? The best way to answer this is by putting together a simple regression model.

I included all the demographic factors that could have an impact: education, income, age, gender, and race. But then I added two measures of religion: affiliation and attendance alongside a measure of political partisanship. A positive coefficient indicates an increased likelihood of believing that college is a smart investment.

Two factors drive down the perception of college: being white and identifying as a Republican. Holding other things constant, there’s a .33 decrease in predicted probability that a Republican is to believe that earning a college degree is a smart investment and it’s just slightly lower for being white (.25 lower predicted probability). There are a couple of factors that don’t matter in either direction. These include: gender, religious affiliation, and age. From this data source, we can’t say with any certainty whether being a none or being an evangelical have an appreciable impact on views of higher education.

So what drives up the perception of college? I can find three variables that have a positive coefficient: household income, religious attendance, and having a higher level of educational attainment. The one that is the most predictive is level of education, which should come as little surprise given the nature of this question. Also, the household income variable predicting a greater level of support for earning a college degree also makes logical sense.

However, church attendance being positively related to the perception of higher education is one that is worth some reflection. As I’ve written about extensively before - the people that are the most likely to attend religious services weekly are those with graduate degrees. The least likely are those who didn’t finish high school. This is a pattern I keep seeing in the data: attendance, education, and trust tend to reinforce one another. Educated people tend to be more trusting and be more religiously active. Which one of those factors drives the others is much more difficult to ascertain, but it’s becoming hard to ignore how these ideas tend to create a self-reinforcing cycle.

So are religious people more skeptical of the value of higher education? I don’t really think that comes through in this analysis. In fact, there are some aspects of religion that may incline an individual toward positive aspirations toward education. As readers of this newsletter have grown accustomed to me saying: nothing about the world of religion is simple.

Code for this post can be found here.

Your regression analysis here finds that the two strongest negative predictors of faith in higher education are being white and identifying as Republican. That’s a politically loaded finding, but I think it reflects years of cultural messaging from conservative media and politicians, especially if we recall how often colleges are discussed as bastions of liberal indoctrination.

Add in high tuition costs, DEI controversies, and campus protests, and it’s easy to see how the image of academia has shifted from ivory tower to ideological battleground.

What’s notable, though, is your finding that religious affiliation itself isn’t a significant predictor of views on higher ed; instead, religious attendance is. In fact, regular churchgoers, particularly those with graduate degrees, tend to view higher education more positively.

This data would contradict any tidy claims that religion is inherently anti-intellectual. It seems to me the real divide may be cultural orientation: whether someone is actually embedded in institutions that foster trust and engagement, or alienated from them entirely.

In terms of the way education is structured, I think there's a lot of regret that the system is what it is, even if we have different ideas about how to repair it (if that's even possible).

I would predict that many of the college-educated people agreeing with the statement "college is not a smart investment" are mainly trying to express that they think the system is broken and overpriced. But in most cases they're nonetheless going to direct their own children (or grandchildren) towards college, while trying to be smarter about it. I'm mainly of this view.

The schools that are getting most badly crushed by the enrollment cliff are those that plainly offer bad value for the money. Above all, private schools that are less selective than nearby public schools, priced much higher, without much of an endowment for scholarship money, and whose survival has mainly relied on recruiting middling athletes to play sports in pursuit of a hopeless dream.

In terms of actual intent to send one's kids to college, I suspect there's a bigger divide than appears in these numbers between those who did, and did not, complete college themselves. If you could break out the "some college" crowd here, I'll speculate that they might be the most hostile to it: those who attended college and didn't flourish there or otherwise didn't see enough value to stick with it, and possibly ended up with some loans but no degree for their trouble.