Faith Meets the Future: Religion and the Gene Editing Divide

Gene Editing Is Here—But Public Opinion Is Stuck

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

The number of advancements occurring in the medical community every year are astounding. For instance, there’s now an incredibly effective treatment for cystic fibrosis and hepatitis C. For people with cancers that are responsive to immunotherapy, there have been incredibly promising drug trials. One, reported in the New York Times, described a trial of 103 people where just five had a recurrence of cancer within five years. And more and more Americans are taking GLP-1 medications that lead to significant and sustained weight loss. More recent studies have found that those taking the drugs are also seeing a reduction in smoking and alcohol consumption, too.

But among all the things just listed, it’s hard to really pinpoint an ethical concern. Many of these drugs just do what pharmaceuticals have been doing for decades - reducing illness and treating disease. None of these therapies make any permanent changes to the human body. However, the next wave of treatments may wade into murky philosophical and religious territory. Just a few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a stunning headline, “Baby Is Healed With World’s First Personalized Gene-Editing Treatment.”

The child was born with an incredibly rare genetic disorder that would almost certainly end his life at a very young age. Doctors sprang into action and developed a highly personalized gene editing treatment for the baby’s genetic abnormality. The treatment worked, and his team of doctors and nurses is preparing for the patient to go home—an outcome that was medically impossible just a few years ago.

This is the first case of successful gene editing that’s ever been reported and it certainly won’t be the last. But the religious response to gene editing is decidedly mixed. Some evangelical organizations have likened some versions of the process to ‘playing God.’ While others, like the Vatican, have taken a more nuanced position on the topic - saying that therapeutic gene editing should be permitted as long as the scientific process doesn’t include the destruction of embryos.

Back in 2021, the Pew Research Center fielded a survey that included a battery of questions about gene editing practices and implications. That data is hosted on the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). There’s a lot to learn here about what factors shape people’s views of the technique and how much (or how little) religious concerns play a role.

The questionnaire asks respondents, “Do you think the widespread use of gene editing to greatly reduce a baby's risk of developing serious diseases or health conditions over their lifetime would be a…”

In the entire sample, I think the best description of the results is ambivalence. About 30% of the public thinks this is a good idea and the exact same share thinks it’s a bad idea. The plurality response was “not sure” at 40% of the general public. That’s a pretty good indication to me that the average person is not spending a whole lot of time thinking about the implications of gene editing.

There is some variation based on religious traditions, though. The most supportive of gene editing are the non-religious (37% think it’s a good idea) and the non-Christian faiths (38%). There’s a noticeable drop off between these two groups and the Christians in the sample. Among Catholics and non-evangelical Protestants, the distribution of responses really mirrors the overall sample pretty well. That leaves the real outliers in the survey — evangelicals. Just 19% of them believe that gene editing is a good idea and 42% think it’s not a smart move.

What strikes me, though, is how many respondents chose ‘not sure.’ In the whole sample it was 40% and each religious group didn't vary much from that benchmark. Again, I don’t get the sense from the public that there’s been a lot of concentrated thought on the idea of gene editing.

But, the Pew survey tried to make the question more real by asking if they would allow gene editing on their own child - with the response options ranging from ‘definitely yes’ to ‘definitely not.’

It’s so incredibly interesting to me just how divided the public is on this topic. In this survey, 49% of folks leaned in the direction of allowing gene editing on their own baby. That’s statistically a dead heat. But I do need to point out that only 16% of people would ‘definitely’ want this for their child, while about a quarter were completely opposed.

That same general trend from the previous question resurfaces here. The non-religious and the non-Christians were the most supportive. Nearly six in ten nones would favor gene editing for their child. Catholics and non-evangelical Protestants were about evenly split on this question. The evangelicals are more opposed than any other group - just one third of them would allow gene editing on their child, while almost 40% are completely resistant to the idea.

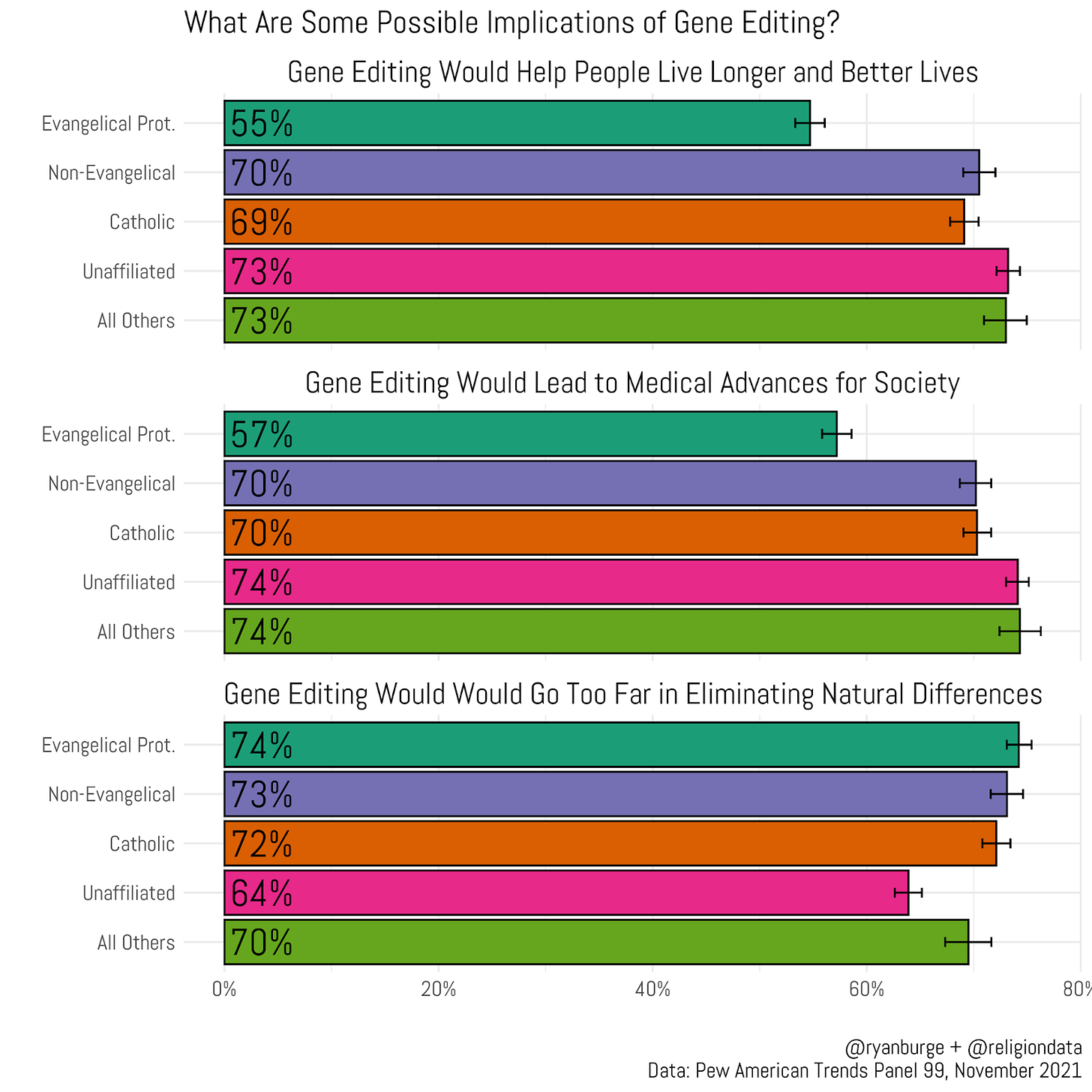

The Pew data also includes questions about potential implications of gene therapy like helping people live longer healthier lives, lead to medical advances, or it would go too far in eliminating natural differences between people. This is the share who said that gene editing would ‘definitely’ or ‘probably’ have these implications.

I think that the biggest thing that jumps out here is that evangelicals are much less likely to see the upside in gene editing techniques. A bare majority believe that it could lead people to live longer, healthier lives - that’s about 15 points lower than any other group. The same is true for gene editing leading to medical advances. They are about 15 points less likely to see the benefit in this area, as well.

Now, I will say this - there’s a lot of consensus on the question of whether gene editing would go too far in eliminating natural differences between people. I think it’s likely that those taking the survey believed that people would use gene editing to ensure that their sons or daughters had an above average height or possessed a certain eye color or hair color. All Christians look exactly the same on this question.

That, however, leads me to a pretty tough question: why is it the case that evangelicals tend to be so much of an outlier compared to other Christian groups? The first factor I took a look at was age - I was thinking that maybe people of childbearing age would feel differently about gene editing compared to those who had long moved beyond that phase of life.

I was pretty disappointed to see just how little age really mattered for most of these groups. I mean, you can see that opposition to gene editing is highest for evangelicals between the ages of 30 and 64, but there’s still a lot of opposition among the youngest and oldest in this subsample, too. In fact, evangelicals between the ages of 18 and 29 were more opposed to gene editing than basically any other age group of the other four religious traditions in this survey.

You just don’t see much variation inside each religious tradition. Among non-evangelical Protestants, opposition is about 25% of the sample from 18 to 64 years old. For Catholics you do see quite a bit of variation between the youngest adults compared to those in their thirties and forties, but then it drops back down among those who were at least 50 years old. Looked at in totality, I just don’t know if I see any really strong evidence that this is a generational thing.

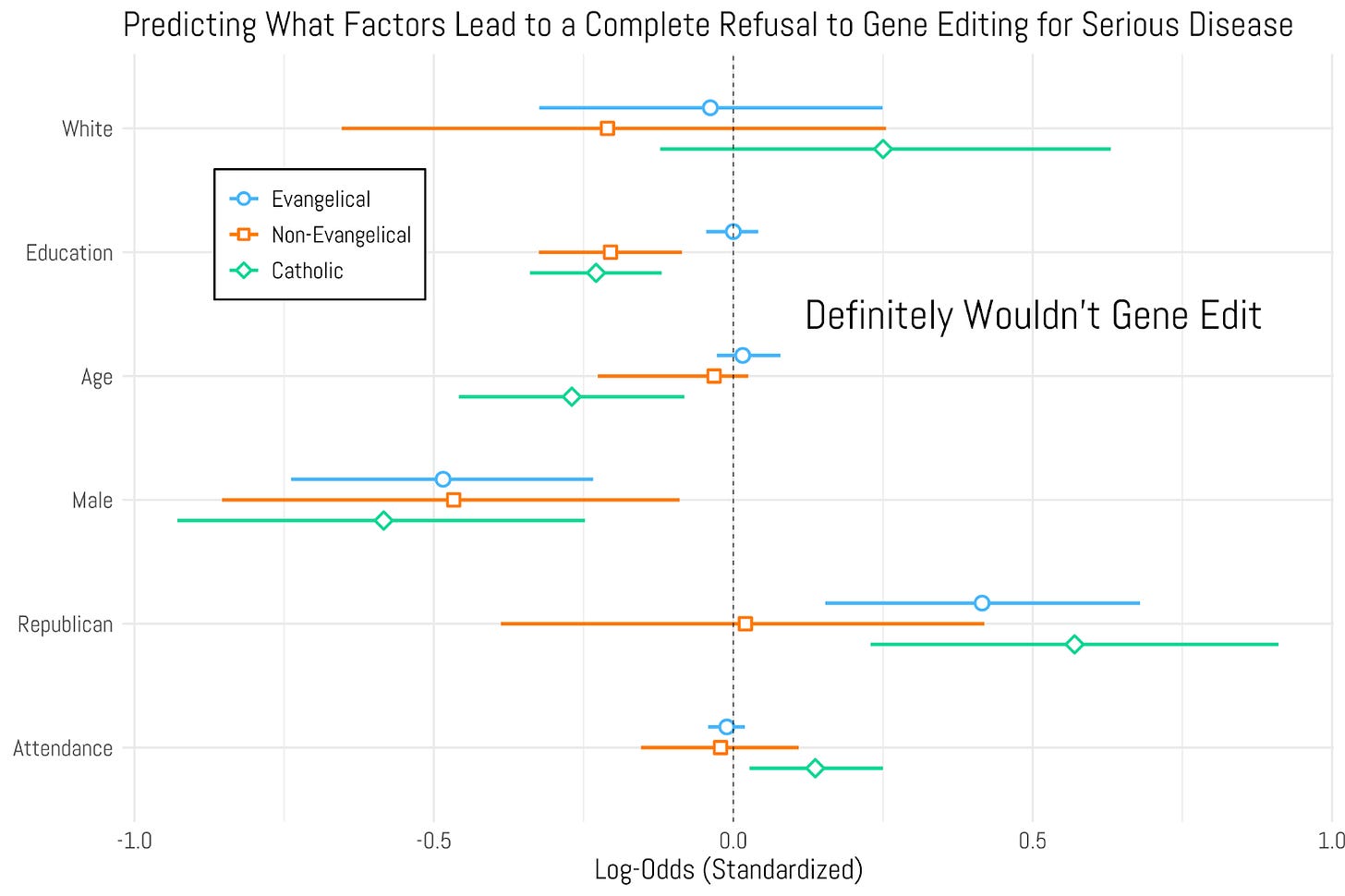

Finally, I wanted to explore a logistic regression. Positive values indicate that those factors made someone more likely to express strong opposition to gene editing on their own child. Negative values indicated more openness to the practice. I ran the model for each of the three Christian groups I had constructed.

Only a few variables emerged as strong predictors of opposition to gene editing. The most notable were when evangelicals and Catholics identified as Republicans. Which means that politics is clearly driving opposition for both those groups. The only other variable that was positively signed and significant was Catholics and Mass attendance. The more religiously active they were, the more likely they were to oppose gene editing.

What drove down opposition? Education for both non-evangelical Protestants and Catholics. Older Catholics were more in favor of gene editing. Christian men, across the board, were more open to the idea of using gene editing on their child compared to women. I would love someone to chime in and make sense of that one. But that’s about the extent of what the model can tell us.

You know what I think is going on here the more that I poke around on this data? There’s a classic paper in political behavior called The Two Faces of Issue Voting by Carmines and Stimson. Their thesis is this: we can divide topics into ones that people can easily form an opinion about (gay marriage, abortion) and those that are much more difficult to grasp (free trade, foreign policy). I think that gene editing is clearly a hard issue. But it’s also an issue that, at the time of this survey, had very low salience. It was nothing more than a thought exercise. As we see more and more media coverage of successful gene editing techniques, we could expect the public to move on this issue.

The other thing that jumps out to me is that religious traditions (outside evangelicalism) just doesn’t seem to matter much. That would suggest that religious leaders are not making the issue of gene editing a talking point in sermons or Bible studies. That too could change given the rapid advances in technology.

In other words, we need these questions to be asked again in about ten years. We would expect the responses to change pretty dramatically.

Code for this post can be found here.

As everyone who has taken care of patients knows, what I would do and what I must do to avoid catastrophe get different responses. No intubation, amputation, insulin for me becomes go ahead doc in the moment of gotta do it right now. The other thing that happens with medical innovations is that they go from just a few with high risk to proven benefit that people find hard to turn down. Antidepressants were widely rejected by much of the public until about 1990 when Prozac established widespread efficacy and safety. As your friends and neighbors got cheerier and told you about it, the acceptance of a depression diagnosis and treatment accelerated. My guess is that gene therapy, now high risk for desperate conditions, will find their way to more common less threatening conditions. With that comes public acceptance. Data to random responders on theoreticals cannot capture that medical reality.

I think another interesting graph would be using the same groups would be a straight forward question 'Do you believe gene editing is Moral, Immoral, or I don't know. The answers shown in the charts displayed lead us to make some assumptions about that, but I'm a more of an in your face guy.

At an actuarial convention decades ago an actuary discussed statistics this way:

"Statistics are like bikinis," he said, "What they reveal is very interesting but what they hide is vital."

Not the kind of story one tells in our more sensitive culture today, but one that is very confessional about how stats work.