Everyone Lies About Voting (Even the Religious)

A deep dive into the massive gap between who says they voted and who actually showed up in 2024.

I know what you are all pining for—a super nerdy post where I get into the weeds of survey methodology and point out something that you didn’t think you needed to know but are really excited to learn about. For instance, I wrote a post about people who check the “something else” option when it comes to religion, then write their actual religion in a text box. Which, for those following along at home, is my own version of hell. Parsing through thousands of responses that are often nonsensical and misspelled is not how I like to spend my time.

Well, in today’s edition of “how the sausage is made,” I am going to highlight an innovation in the survey world that is worth knowing just a bit about. It’s called “voter validation.”

Most surveys simply ask people whether they voted. Seems pretty straightforward, right? There’s actually a huge problem with this. A lot of respondents say “yes” even when they didn’t. It’s not always intentional—sometimes people genuinely forget, sometimes they want to present themselves in a positive light, and sometimes they just click the answer they think they’re supposed to give so they can take part in the rest of the survey. But the end result is the same: self-reported turnout numbers are almost always inflated.

I remember advising a big-time religious leader a couple of years ago who wanted to know what evangelical turnout was in the most recent election. I pulled up the Cooperative Election Study and ran a quick calculation. It was over 95%. Yeah, that doesn’t pass the sniff test.

There’s a way to mitigate this, though. Voter validation tackles that problem by using public voter files. Here’s how it works: after the election, survey firms match respondents to official state voter records. Those records don’t tell you who someone voted for, but they do tell you whether they actually cast a ballot. It’s just a way to “check our work,” really.

Of course, it’s not perfect. Not everyone can be matched—names change, people move, and some states limit access to voter files. But overall, validated turnout is vastly closer to reality than whatever people type into an online survey.

Why does this matter? Because if you want credible estimates of who actually votes—by religious tradition, by demographic group, or by political preference—voter validation is the gold standard. And as you’ll see below, the gaps between what people say they did and what they actually did can be… substantial.

Here’s what I mean.

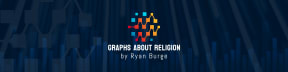

In the 2024 Cooperative Election Study, among all the respondents who took both portions of the survey (the one right before and right after the November election), the self-reported turnout rate was an unbelievable 97%. Yes, that’s the reported number. It’s not a typographical error. What was the actual calculated turnout according to the Census Bureau? 65.3%.

But this is where voter validation kicks in. When the research team at the Cooperative Election Study started matching respondents to actual voter files, they found that the actual turnout rate in their sample was only 59%. This means that roughly four in ten people who told the survey they voted didn’t show up in the voter file. That’s not to say that all of those folks purposefully lied, but undoubtedly a significant portion did.

Now, here’s the religion pivot. Let me show you the reported turnout for each level of religious attendance compared to the voter-validated measure.

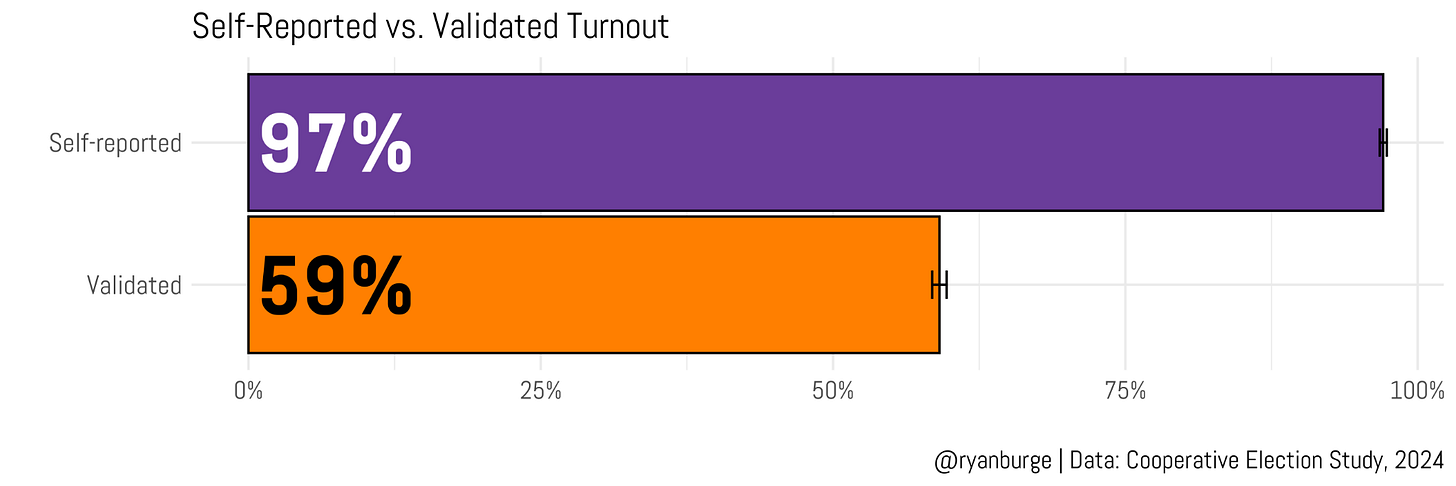

Given that first graph, it should come as no surprise that almost everyone in the survey says they actually voted. Among folks who say they never attend a house of worship, 97% claimed to have cast a ballot in the 2024 presidential election. Among those who reported attending church multiple times per week, it was 99%. In other words—essentially all of them.

What do the voter validation measures say? Well, the numbers are a whole lot lower. The turnout metrics range from 54% among folks who indicated monthly attendance to 63% among the weekly attending crowd. What I find noteworthy here is that the percentages don’t really deviate that much. In fact, I’m not sure we can make any strong claims about weekly churchgoers being that much more politically active than the “never” attenders. The difference is actually just a few points.

But here’s where it gets a lot more fun for me—I did the same calculation (reported turnout vs. voter validation) for each individual religious tradition.

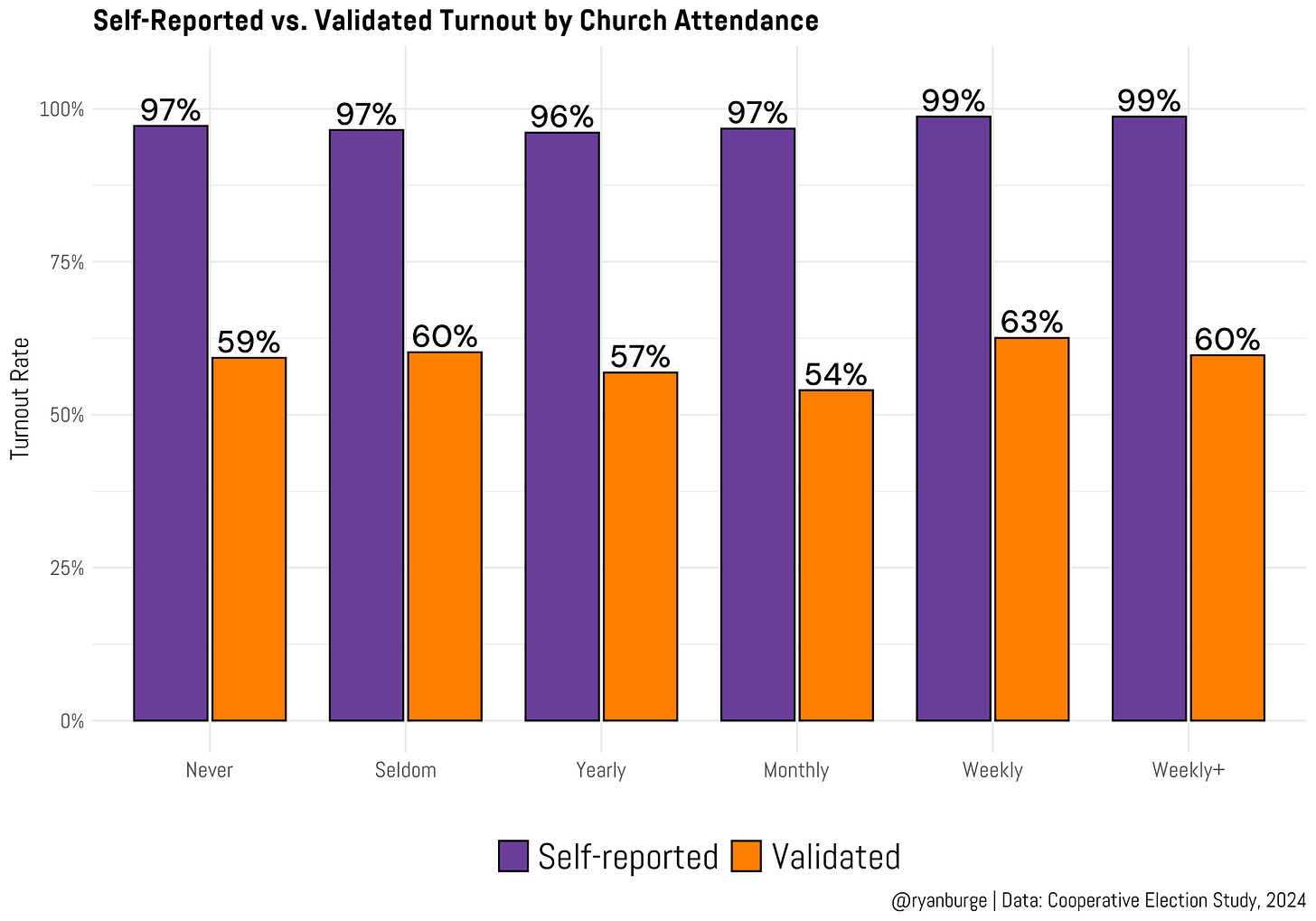

The purple bars, which are the self-reported numbers, are actually pretty boring. As has become the norm here—almost everyone says that they voted in 2024. I mean, does anyone actually believe that 99% of white Catholics were at a polling place in November? It’s the same share for white evangelicals. Lots of groups are in the 97%+ group. The lowest self-reported turnout comes from Muslims at 89%. Hindus are just a bit higher at 93%.

But those orange bars, which denote the validated turnout metrics, tell a much different story. According to the best methodology we have available, the religious group with the highest level of turnout is Jews at 75%. Mainline Protestants are just behind them at 72%. Then, there are white evangelicals at 69% and atheists at 67%.

Which groups are the lowest? Well, the real outlier here is Muslims at just 26%. No one else even comes close. But the next in line are non-white Catholics at 40%, Black Protestants at 42%, and Hindus at 44%.

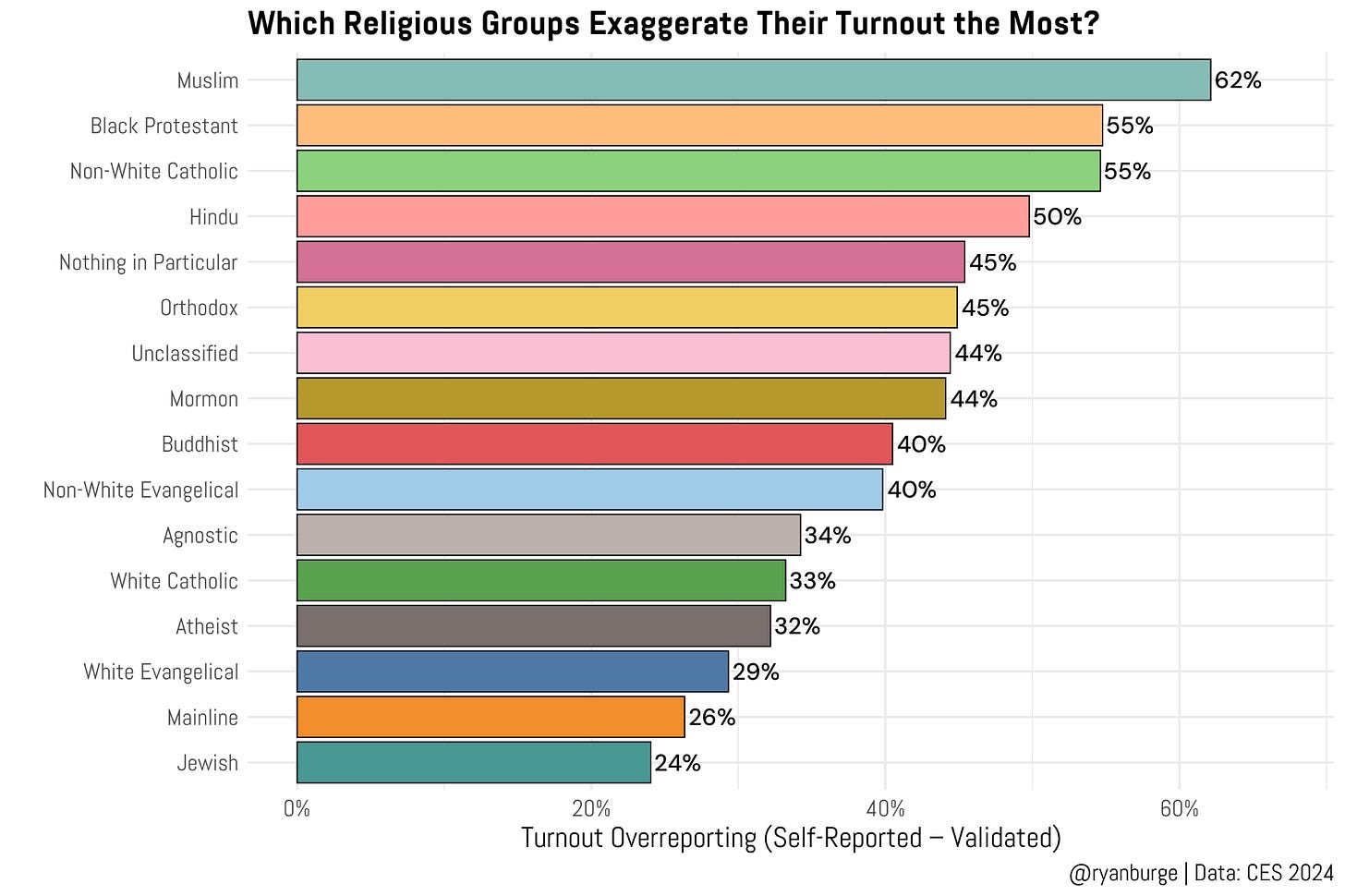

But I wanted to simplify this and pull together a single graph that answers the simple question: which religious groups exaggerate their turnout the most?

The clear front-runner on this metric is Muslims in the sample. Remember—the self-reported share of Muslims who cast a ballot in 2024 was 89%. The actual share who were validated was only 26%. That’s a gap of about 62 percentage points. The next two groups in line are Black Protestants and non-white Catholics, with a gap of 55 percentage points each.

The groups at the bottom of the graph are the ones with the smallest gap between the self-reported numbers and the voter validation stats. For Jewish respondents, the gap is 24 points, which is two points lower than mainline Protestants. White evangelicals are third on this scale, with a gap of 29 percentage points between the number who said they voted and the share that could actually be validated.

You can pretty much figure out why the order is the way it is—self-reported numbers are insanely high for every single group. I mean, the lowest figure was among Muslims at 89%. But many groups were 95%+. So, really, the only metric that matters in this calculation is the validated share. High-turnout groups are going to have less misrepresentation than lower-turnout groups.

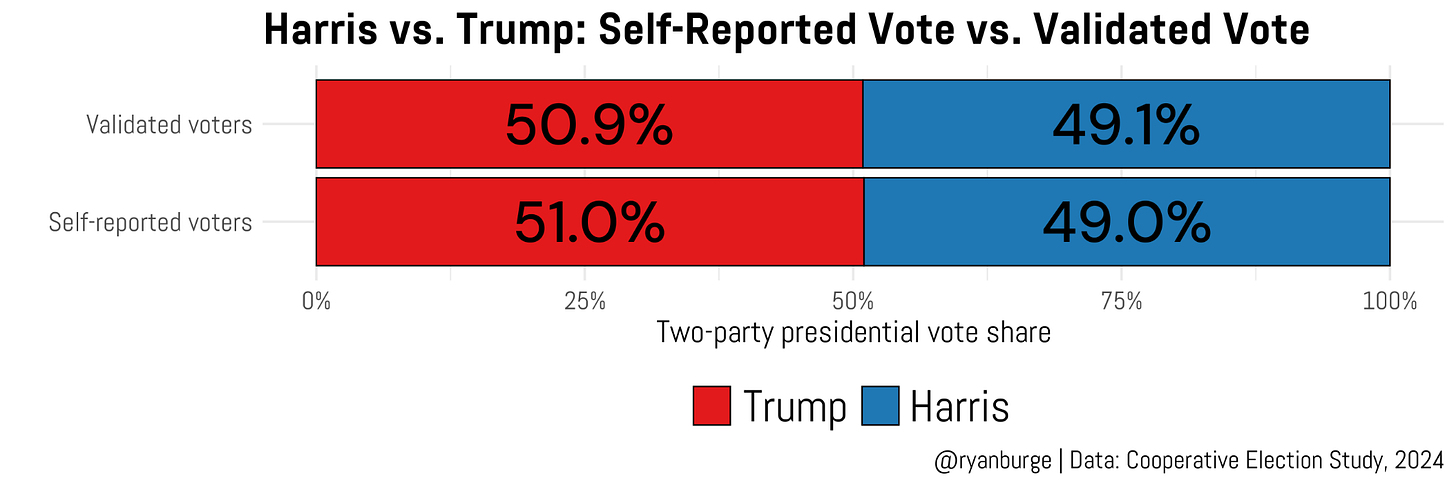

I know your head is spinning right now—maybe all the data that Ryan has shown us in those post-mortems about the 2024 presidential election are wrong. If 40% of the folks who say they cast a ballot actually didn’t, that means the Trump or Harris share could be way off. But, I will assuage those fears now. Here’s the distribution of votes among validated voters compared to self-reported voters in 2024.

Yeah, there’s no real difference at all between the two groups. How can that be? Well, voters lie about turning out, but they don’t really lie about which candidate they supported. They want to seem civically engaged, but they don’t feel the same pressure to distort their candidate preference. So the vote margins remain incredibly stable, even as turnout is wildly overstated.

And yes, the weighting plays a role here, too. The CES weights are designed to make the sample look like the actual electorate. So even though lots of people overstate whether they voted, the weighting process pulls the partisan balance back toward reality. In other words, people may fib about turning out, but they don’t lie in ways that systematically help Trump or Harris—and the weights correct most of that anyway.

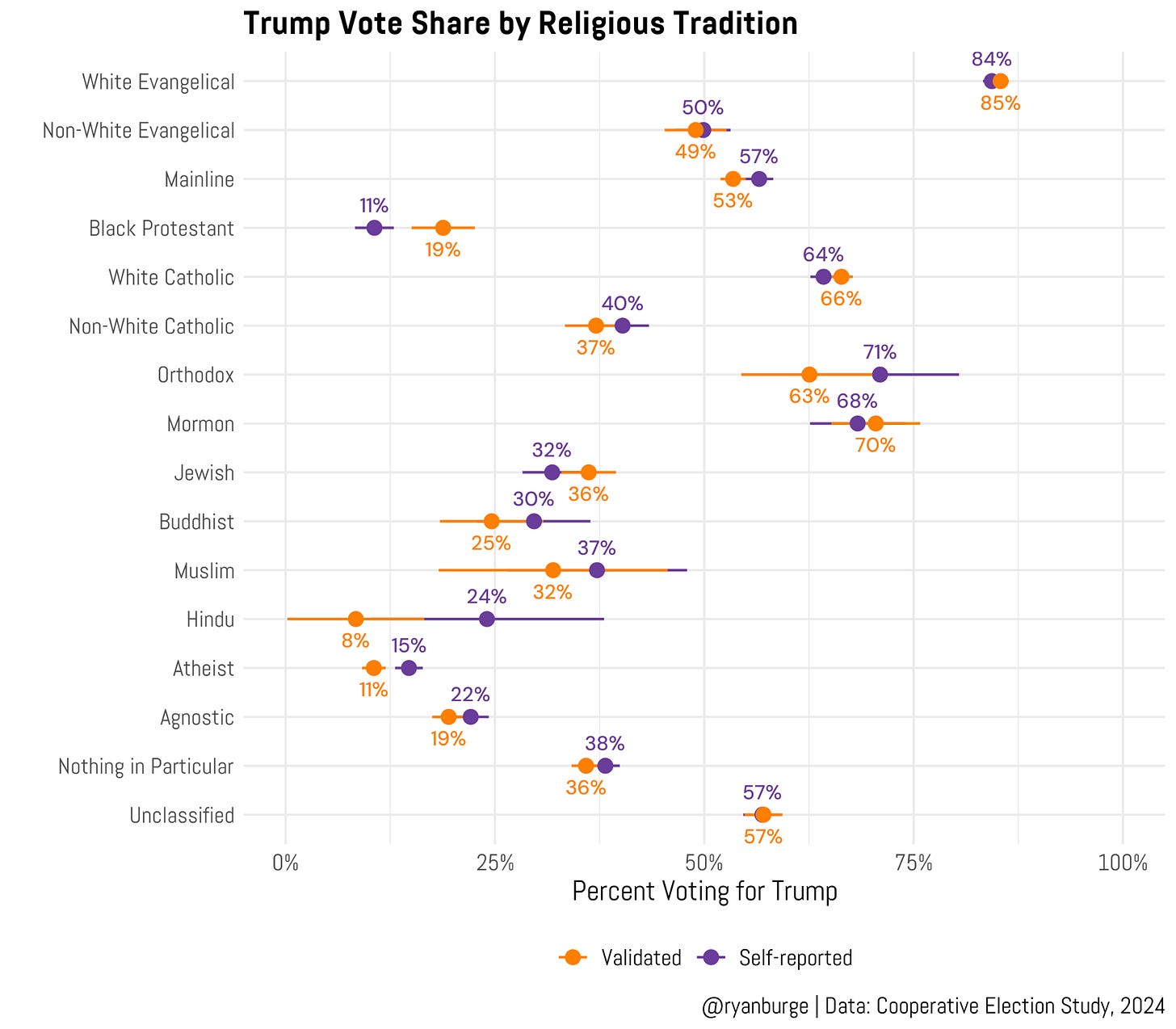

But that’s at the very top level, of course. If we drill down into each individual religious tradition, there are some differences in Trump’s vote share when comparing the self-reported data to the validated subgroup.

There’s a general pattern that emerges from this analysis—for a lot of the bigger groups, there’s really no difference in the vote breakdowns. That’s the case with evangelicals, mainline Protestants, Catholics, agnostics, and the “nothing in particular” group. Each one is numerically fairly large, and the confidence intervals indicate that the estimates are not statistically different. There are a number of smaller groups where the estimates are not statistically distinct, too: Latter-day Saints, Jews, Buddhists, Muslims, and Hindus are all in this category.

What about groups where the two estimates are statistically distinct, though? There are a handful worth flagging. Among voter-validated Black Protestants, 19% cast a ballot for Donald Trump compared to only 11% of those who self-reported that they voted. For atheists, the two numbers were reversed: among self-reported voters, Trump did four percentage points better than in the validated subsample.

One wrinkle here is that the gap isn’t random; it tells you something about who actually makes it into the validated-voter pool. Take Black Protestants: the folks who both (a) show up in the voter file and (b) complete a post-election survey tend to be older, more stable, and a bit more socially conservative than the broader Black Protestant universe. This nudges their Trump share up relative to everyone who simply claims to have voted.

Among atheists, it’s probably the mirror image: the most committed, high-turnout atheists are also the most reliably Democratic, so the validated subsample is a little bluer than the wider group of people who say they voted. Layer on top of that the relatively small sample sizes for these traditions, and you’re going to see some real—but still interpretable—divergences between the self-reported and validated estimates.

I hope this post helps you all understand the lengths that we go to to get the numbers as accurate as possible. Polling is insanely hard. It’s both an art and a science. I know many people working in the field, and they all have a common goal: get it right. Voter validation is one of the tools in our arsenal to get a more precise picture of how ballots are cast by Americans.

As you can probably tell from this post, it doesn’t really shift the actual vote composition that much, but it does provide a more accurate picture of who is showing up on Election Day.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

My medical office version of this has roughly the same theme, though perhaps with a dark side. Everyone takes their medicines when you ask them. When you look at their BP, cholesterol levels, HbA1c or objective lab metrics, the doc wonders why his Rx don't do as well as what the journal studies report. Some bring their pill bottles to their office visit, most don't even when asked. Our validation method is the electronic Rx record which tells when the last refill was issued. People miss more pills than they realize or admit if they do realize. And how much do you drink? Very little but the MCV on the CBC is always 103 fL. That we can't validate.

Lacking Ryan's elegance in figuring out who does not convey to the doctor what he/she needs to know, We are left with our reptile brains to profile patients by our stereotyped impressions, not always accurately. In the 10 minutes in the exam room we have to decide whether to increase doses, create better systems for compliance at the same dose, send visiting nurses to count pills, or most often accept what we are told.

One of your best posts. Amazing what insights one can get with just means, no fancy econometrics.