Do Americans Care Who Their Boss Is?

Religion helps explain when gender matters—and when it doesn’t

This post has been unlocked through a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment for the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The graphs you see here use data that is publicly available for download and analysis through link(s) provided in the text below.

One of the “evergreen” topics on social media when it comes to religion is what’s often called the Billy Graham Rule. The idea comes from the famous evangelist, who was deeply concerned with living a life beyond reproach. Graham wanted to avoid even the appearance of impropriety that could undermine his work as America’s most prominent preacher. To that end, he adopted a personal rule that he would never spend time alone with a woman who was not his wife.

That practice likely protected Graham from rumor or innuendo about his personal conduct, but it has come under increasing criticism in recent years.

For example, on December 11, 2025, former NFL player Benjamin Watson tweeted about a college head coach who “had a personal rule that he would never be alone with a woman, not even in an elevator.” That comment sparked significant backlash, particularly from women who responded by arguing that “structurally, this becomes a tremendous deficit to women.”

Of course, this debate is about more than whether men and women can share an elevator or an office. It’s really about gender dynamics in the workplace. Do men feel comfortable having a female boss? Do women want to be supervised by someone of their own sex? The answers to these questions often reflect deeper convictions about gender roles in society—views that are frequently shaped, at least in part, by religious teachings.

To explore these issues more systematically, I turned to a dataset recently posted by the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) from the Pew Research Center—American Trends Panel 131. The survey, fielded in July 2023, includes just over 5,000 respondents and focuses on gender and leadership. It offers unusually rich insight into how Americans think about workplace authority and who they would want as their boss.

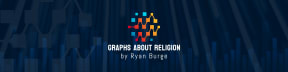

The first question I want to examine was asked only of people who were currently employed. It asked about the gender of their direct supervisor.

In the full sample, 54% of respondents reported that their direct supervisor was a man, while 46% said their boss was a woman. That breakdown actually lines up closely with estimates from the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Put differently, if you gathered 20 supervisors in a room, about 11 would be men and 9 would be women. That’s not perfect parity, but it’s fairly close.

The story looks very different once you split the sample by gender. Among men, a clear majority—about 70%—reported being supervised by someone of the same gender. For women, the pattern tilts in the opposite direction, though less dramatically. Among employed women in Pew’s survey, 62% said that their boss was also a woman.

That describes the current landscape. But what about preferences?

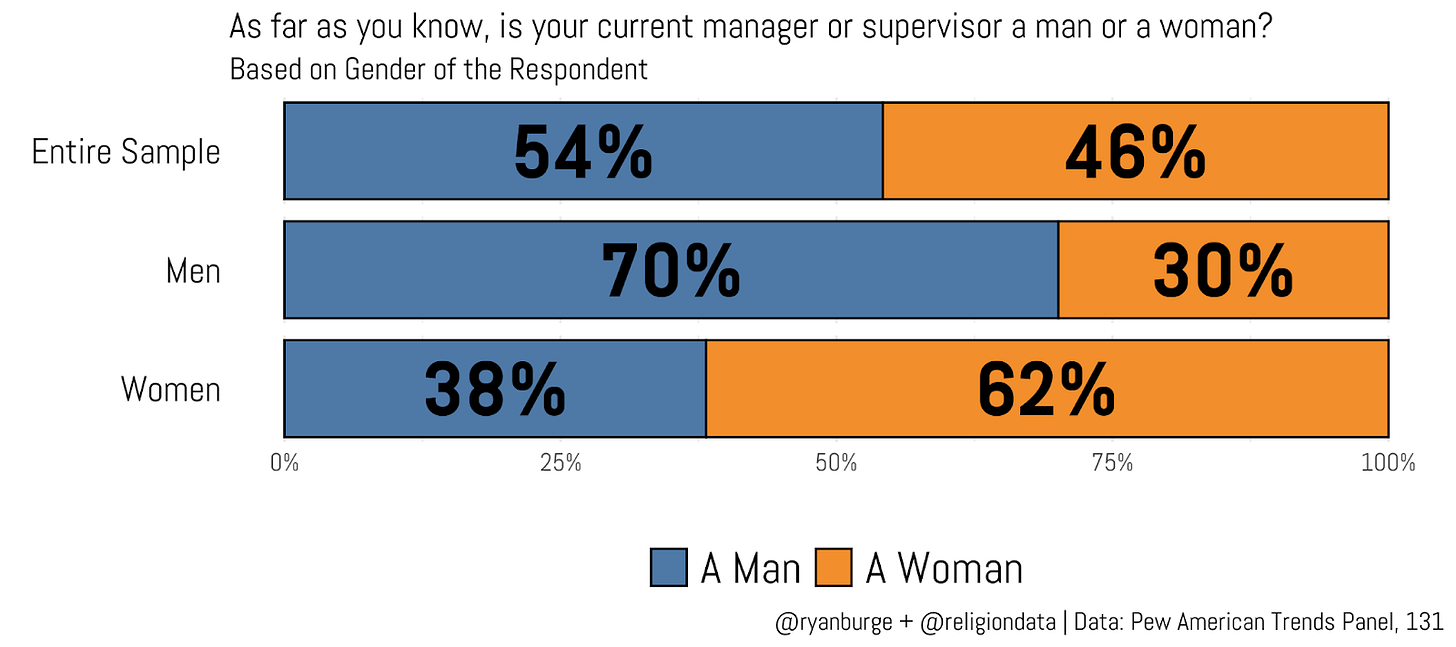

Everyone in the survey, regardless of whether they were currently employed, was asked whether they would prefer to work for a man, a woman, or if they had no preference either way.

The most striking finding here is just how many Americans don’t seem to have a preference at all. In the full sample, 72% selected “no preference.” That share was slightly higher among men (74%) and a bit lower among women (70%). In other words, women were only marginally more likely than men to express a clear opinion about the gender of their supervisor.

Among those who did express a preference, the patterns are fairly modest. About 19% of men said they would ideally work for a male supervisor, while just 8% said they would prefer working for a woman. For women, 17% indicated a preference for a female boss, compared to 13% who said they would rather work for a man. One notable difference is that women were about five points more likely than men to prefer a supervisor of the opposite sex.

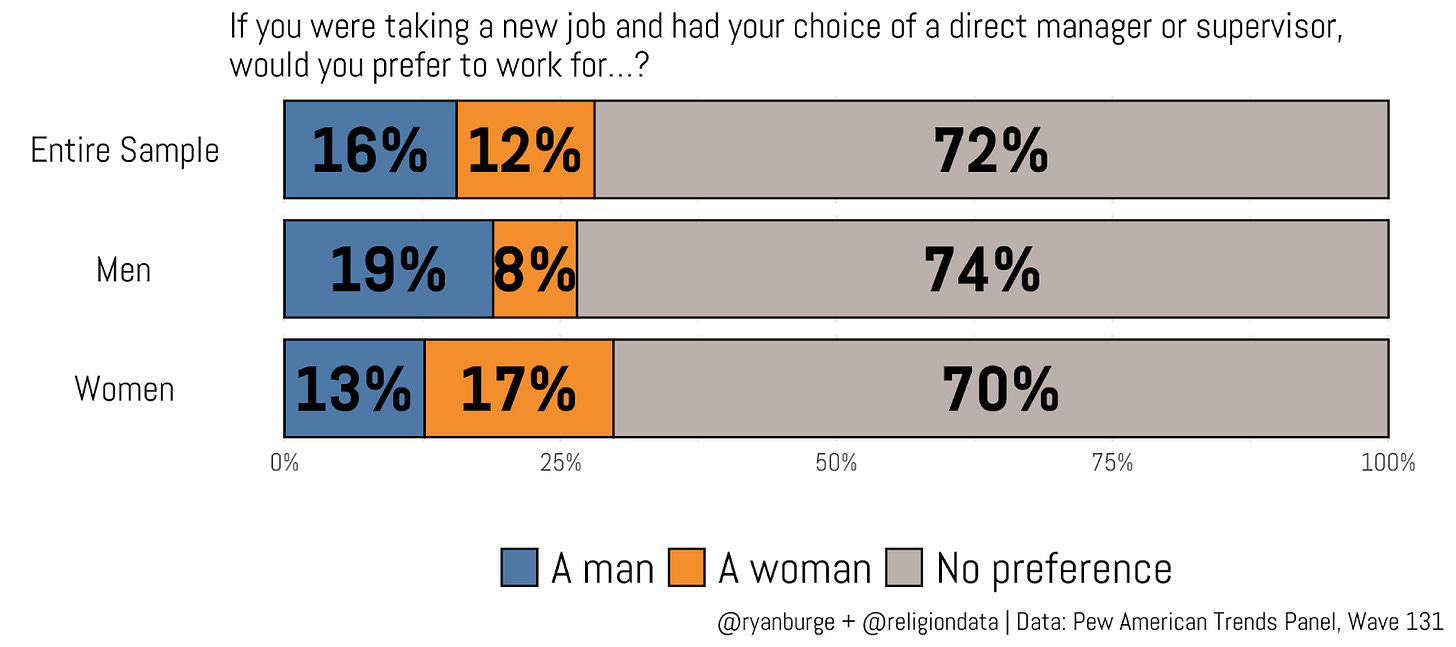

Of course, gender alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Religious affiliation may also shape how people think about leadership and authority in the workplace. To explore that possibility, I divided the sample into six religious traditions and calculated, within each group, the share of men who prefer a male supervisor and the share of women who prefer a female supervisor.

Across most religious groups, there is very little evidence of a gender gap in these preferences. That’s true for non-evangelical Protestants, Catholics, and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular.” One exception is the “other faith” category, where respondents were significantly more likely to prefer working for a supervisor of the same gender. This group includes people affiliated with traditions such as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism. Unfortunately, the sample sizes are too small to examine each of those traditions separately.

Only two groups show a clear gender gap. Among evangelical Protestants, men were about twice as likely to say they would prefer working for a male supervisor as women were to prefer a female boss (26% versus 13%). While it’s impossible to identify the precise cause of this difference, it is plausible that norms common in evangelical spaces—such as the influence of the Billy Graham Rule—may be shaping how men think about gender, supervision, and workplace boundaries.

Atheists and agnostics show the opposite pattern. Among men in this group, just 10% said they would prefer working for a male supervisor. Among atheist and agnostic women, however, 26% said they would ideally want a female boss. Here, broader ideological commitments may be playing a role. Atheists and agnostics tend to be the most left-leaning group on questions of gender and social roles, and men’s reluctance to prefer a male supervisor may reflect a desire to signal support for expanding women’s access to leadership positions.

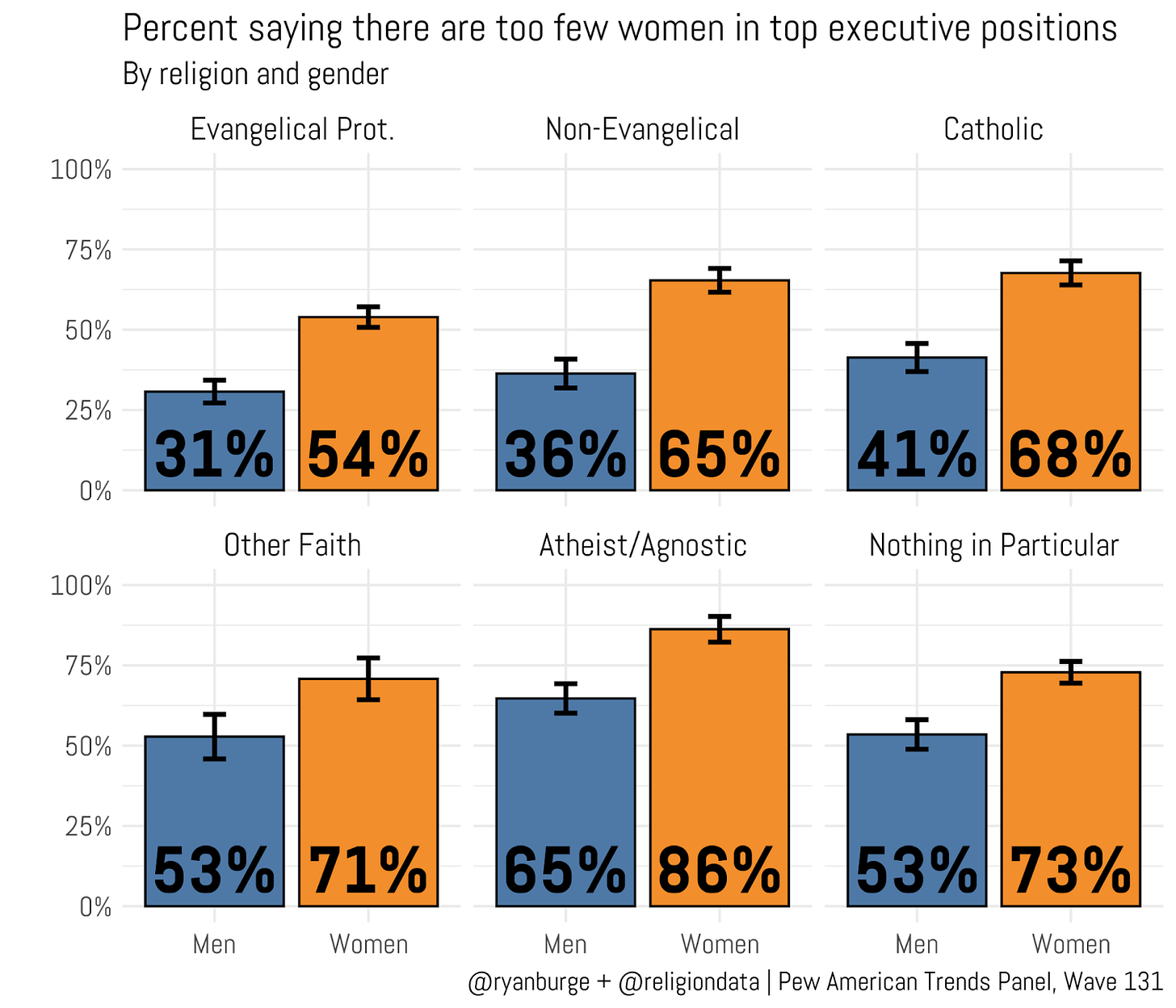

These preference questions are only one window into broader views about gender and authority. The survey also includes items that tap more directly into respondents’ beliefs about women’s roles in business leadership. For example, respondents were asked whether they think there are too many, too few, or about the right number of women in top executive business positions.

I calculated the share of respondents who said that there are too few women in top executive business positions, broken down by gender and religious tradition. The group least likely to hold this view was evangelical men. Just 31% of them said that women should have greater access to top executive roles. Among other male Christians, the numbers were somewhat higher but still modest—36% among non-evangelical Protestants and 41% among Catholics.

By contrast, the men who were most supportive of expanding women’s access to leadership were atheists and agnostics. Compared to evangelical men, atheist and agnostic men were 34 percentage points more likely to say that there are too few women in top executive positions.

The gender gap within religious traditions is also worth highlighting. Among evangelical women, 54% said that women should have access to more top executive roles—23 points higher than men in the same tradition. The gap was even larger among Roman Catholics (27 points) and non-evangelical Protestants (29 points). In fact, the non-evangelical Protestant gender gap was the largest of any of the six religious traditions.

At this point, a few patterns are clear. Atheists and agnostics are consistently more supportive of women in leadership than Christians, and women across traditions are much more favorable toward expanding women’s access to top executive roles than men. But that raises an important follow-up question: among men who are less supportive of women’s advancement, what do they see as the main obstacles keeping women from getting ahead in the workplace?

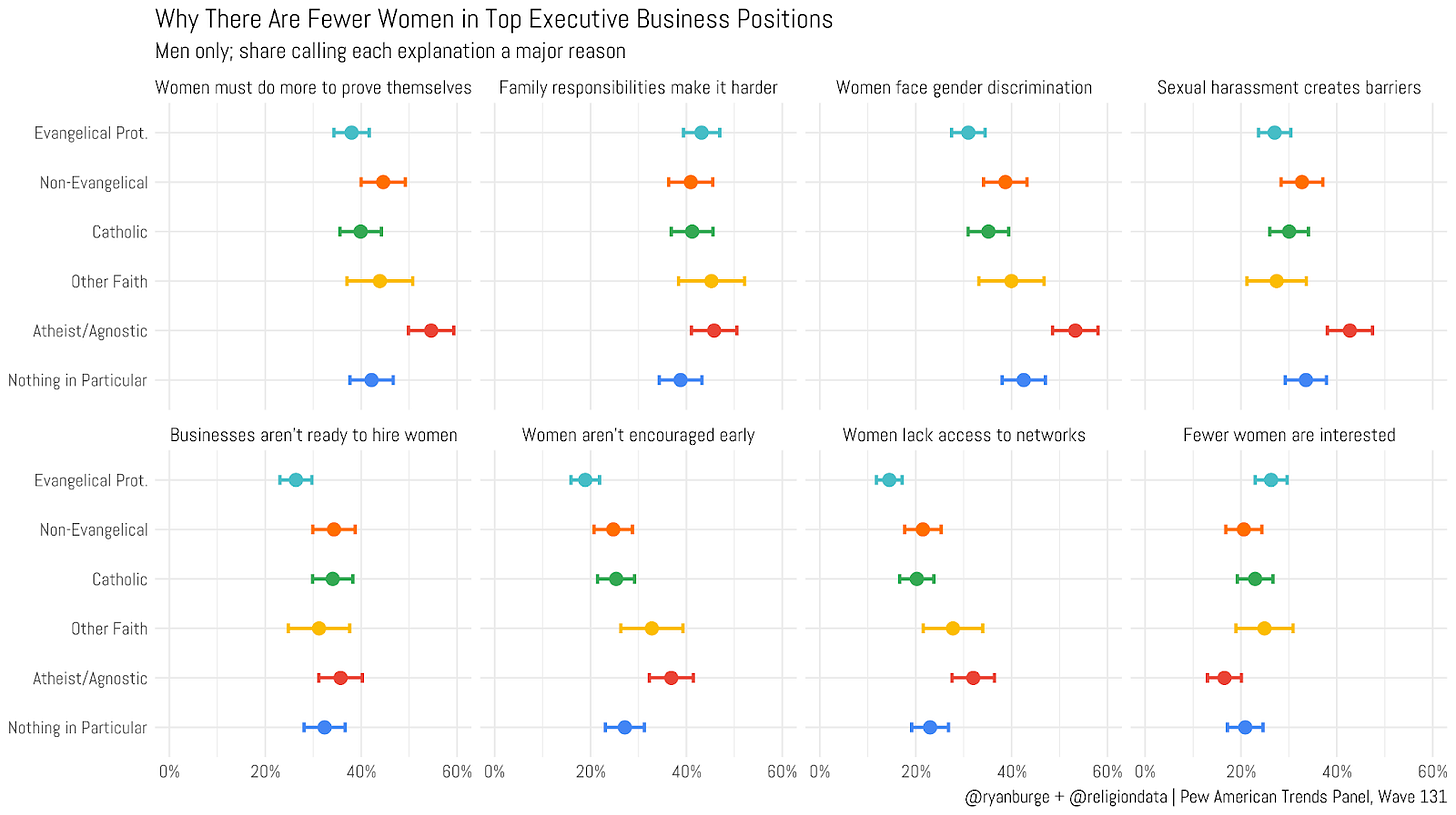

To probe that question, respondents were presented with a series of possible explanations for why women remain underrepresented in leadership and asked whether each was a major reason, a minor reason, or not a reason at all. These included explanations such as women having to do more to prove themselves than men, or the idea that women are simply less interested in executive roles. I then calculated, for each religious tradition, the share of men who identified each explanation as a major reason for the gender gap in workplace leadership.

One thing that immediately stands out is that there isn’t all that much divergence among male Christians on these questions. For example, when asked whether women face more gender discrimination, roughly 35–40% of men say this is a major barrier, regardless of whether they are Roman Catholic or evangelical Protestant. A similar pattern appears on the question of whether businesses aren’t ready to hire women. Overall, there simply aren’t massive differences across Christian traditions in how men think about many of these explanations.

The sharper contrasts emerge when comparing evangelicals to atheists and agnostics. Across several of these statements, the two groups diverge noticeably. Take the idea that women aren’t encouraged early enough to pursue leadership positions. Among evangelical men, just 19% say this is a major reason for the gender gap in supervisory roles. Among atheists and agnostics, that figure nearly doubles to 37%.

The same pattern shows up when respondents are asked whether women lack access to networks that would help them advance. Only 15% of evangelical men identify this as a major reason, compared to 32% of atheists and agnostics. Which, if you think about it, is self-reinforcing. If evangelical male bosses don’t want to be alone with women in the workplace, that inherently will make the women’s network smaller.

This contrast runs through much of the data: evangelicals are far more reluctant to embrace structural explanations for gender inequality, while atheists and agnostics are much more inclined to see discrimination, networks, and institutional barriers as central. Evangelical men, by contrast, are more likely to frame the issue in terms of women’s interest or individual choices.

What’s striking is how much the terrain of these debates has shifted over time. The disagreement today is less about whether women should hold positions of authority and more about why gender gaps persist in the first place. Most men across Christian traditions are willing to acknowledge at least some barriers, but evangelicals are more likely to locate those barriers in personal preferences rather than organizational structures.

At the same time, a sizable share of evangelical men appear relatively comfortable in workplaces dominated by male leadership. Seen in that light, it’s hard to imagine the Billy Graham Rule—or the backlash against it—fading anytime soon. It remains a symbolic flashpoint for much deeper disagreements about gender, power, and the boundaries between personal morality and professional life.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

Probably a safe guess that neither Rev. Graham nor TE Watson would seek a chaperone for medical care from a female ER physician or EKG technician in a cubicle with the curtains closed. Gender separation is always circumstance dependent.

The reality is that few of us get to choose our own work supervisors though some of us get to rate our experience with the boss assigned to us. A more interesting assessment than theoretical preference would be whether the ratings that employees give to the people who already supervise them segregate in any way by either the employee or suprevisor gender or by the employee's religion.

As an evangelical white male pastor I think the responses to this is more about what these groups believe politically than theologically. The split between blaming individual choice or systemic oppression seems to be a political perspective. The Bible says both injustice and choice influence our lives but it doesn't say which is a stronger force in America today for women in business leadership roles.

Unfortunately, the two largest religious denominations in America are the Democratic and Republican parties.