As America Secularizes, Its Soldiers Are Moving the Other Way

A good example of a selection effect.

I can pretty much pinpoint the moment I got the inspiration for this post. I was riding my spin bike in the basement, watching a series on my phone called Band of Brothers. (I know, I know — I should have watched it multiple times by now.) It was released in 2001 and received basically universal acclaim for its gritty and accurate portrayal of Easy Company’s landing on the beaches of Normandy during D-Day and their subsequent 450-day odyssey driving the Germans to surrender during World War II.

It’s excellent, of course. One thing the series does incredibly well is make it plain how every single moment of every single day could have resulted in one of the men of Easy Company losing his life. Many of them did fall to a German bullet or a random mortar round. But others died because of friendly fire or just a freak automobile accident. Death was always around the corner.

Religion was woven in and out of the narrative, naturally. Almost every man in Easy Company had some kind of faith background, with Protestant Christianity, Roman Catholicism, and Judaism all represented. I don’t really know if any of the soldiers said they were atheists. But that got me thinking — what about the modern-day military? I vaguely remembered that the Cooperative Election Study asked some type of question about service in the armed forces, and that was all it took to pull together a couple of graphs.

A lot of times when I poke around based on just a hunch, nothing good comes from it. That’s not at all the case here. There are actually some really interesting insights into the religiosity of the men and women who are serving the United States right now.

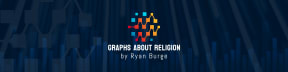

First off, let me describe how the question is asked. It’s a “check all that apply” situation, and there are a variety of options — including being an active member of the military, being a veteran, or having a family member in either scenario. They specifically mention “immediate family,” just for clarity. Here’s how all those permutations shook out in the data collected in late 2024.

Just over half the entire sample (53%) had basically nothing to do with military service. They had never served, nor had anyone in their family. I don’t know what percentage I would have guessed, but that number really jumped out to me. The next most common option was having someone in their immediate family who had served in the past but was not on active duty. That’s another third of respondents. Add those two groups together, and 85% of folks fit into those categories.

Just 5.5% said they themselves had previously served in the military, and another 3% indicated that not only were they a veteran but so was another member of their immediate family. Check this out, though: in a total sample of 60,000 people, the share who said they were on active duty was just 234. That translates to 0.4% of the sample.

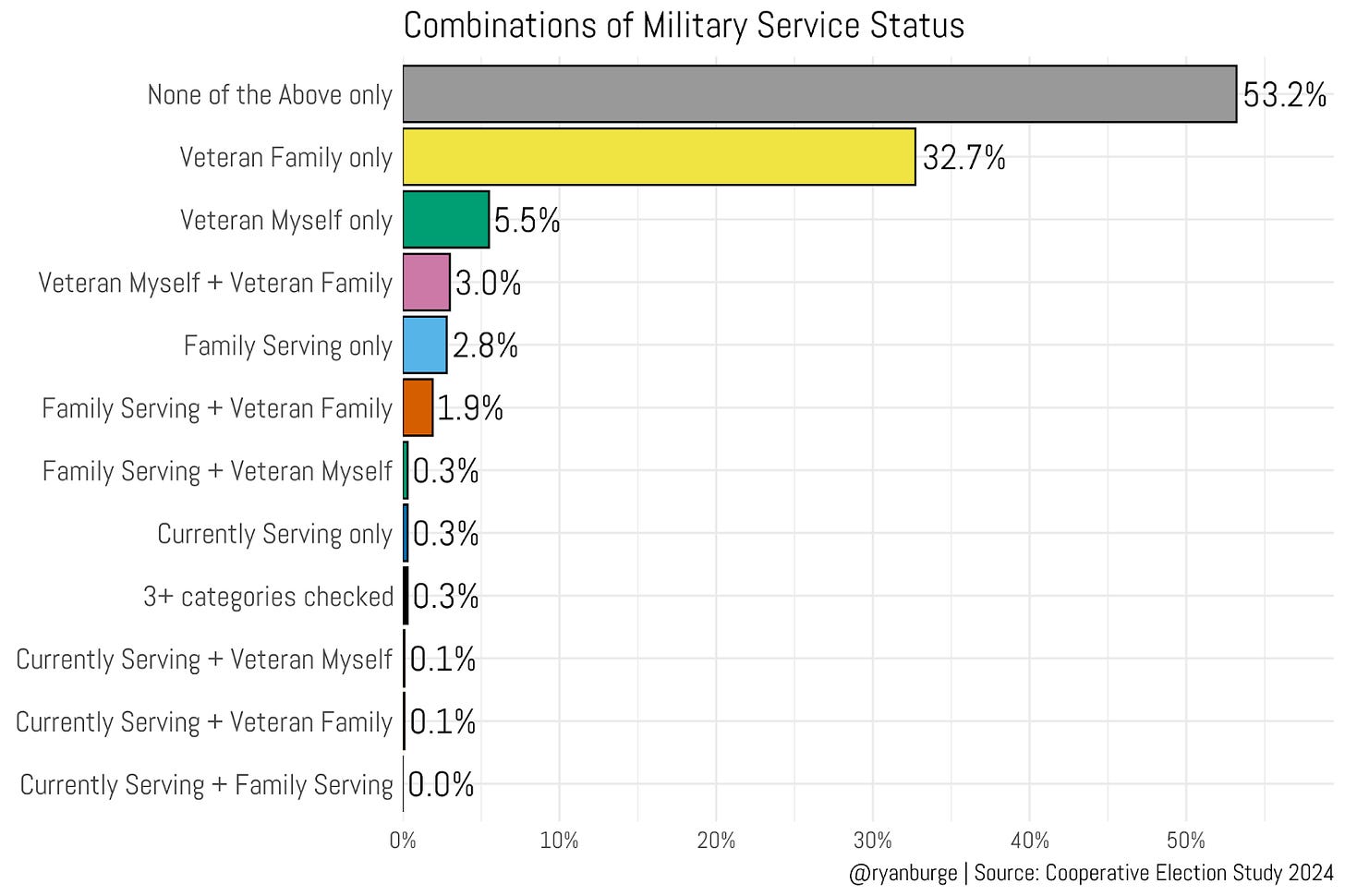

That got me wondering about the share of folks who have zero connection to the military at all. So, I calculated the percentage who checked the “none of the above” box for each birth year in the data. I did this for both the 2010 and 2024 samples to see if anything shifted. This graph is one I’m going to think about often when people ask me: How reliable is survey data?

Notice how the middle part of the graph — meaning those born between 1940 and 1980 — just doesn’t deviate at all when looking at these two surveys? Yeah, that’s exactly what you’d want to see if these instruments are reliable. Two independent surveys, collected fourteen years apart, and the trend line is essentially the same. That’s awesome.

Among folks born in 1940, only 20% had zero connection to the military. For those born in 1960, it was about 50/50. But for respondents born around 1980, 60% checked the “none of the above” option when it came to a military connection. I haven’t seen this fact discussed much at all. The vast majority of Baby Boomers had personal ties to the military. The vast majority of Millennials do not.

I do want to point out how the 2024 line has flattened out, though. For people born in 1990 or later, somewhere between 70% and 75% have no connection to the military.

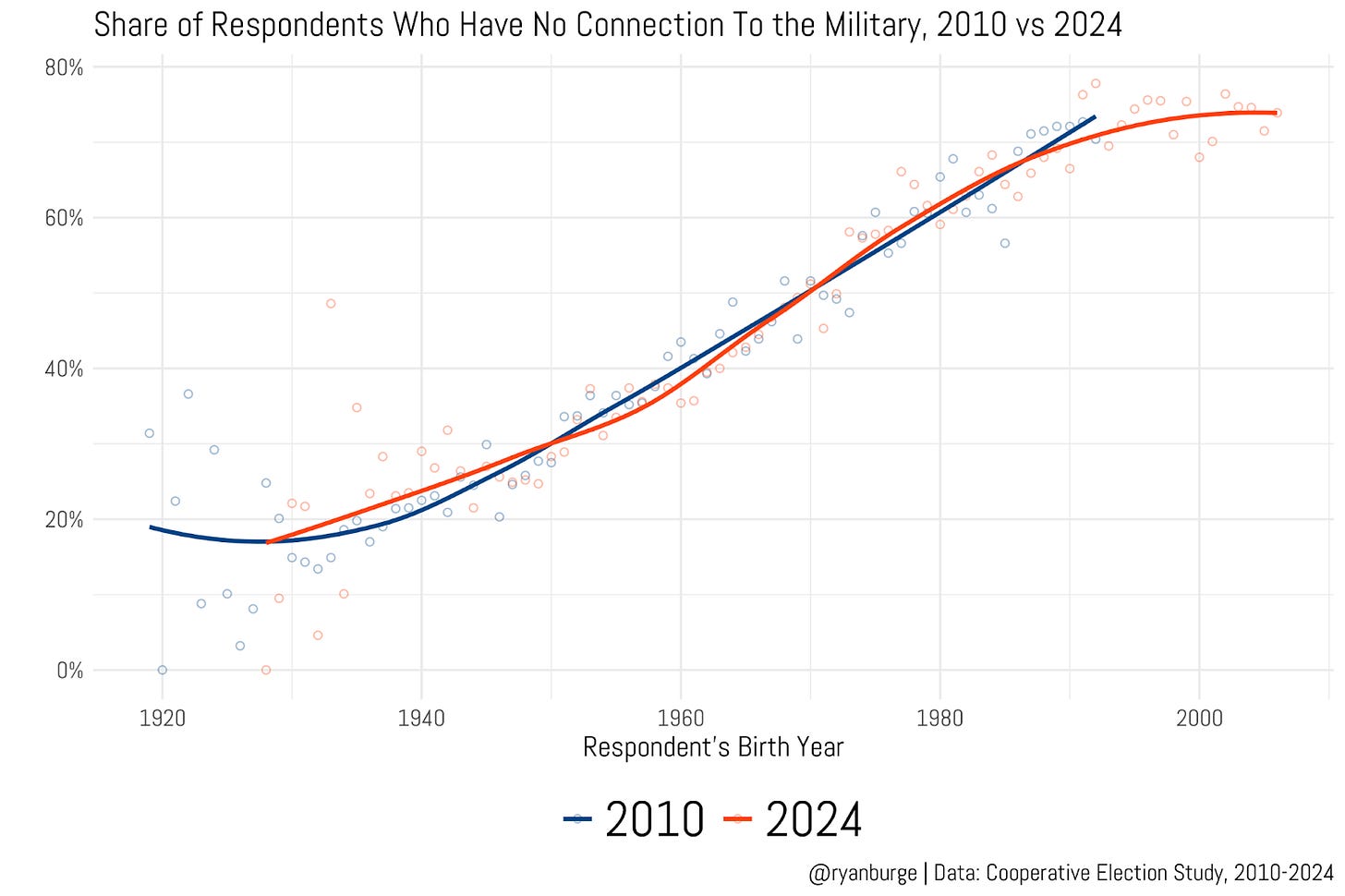

But what about the religious composition of those different combinations from the first graph? I’ve got to admit, this bit of analysis probably isn’t going to go viral.

In my mind, there’s one outlier: those who checked “none of the above.” Just a bare majority of them (51%) said they were Catholic or Protestant. In comparison, 41% of this group identified with no religious tradition at all. That group was easily the least religious compared to the other four.

In the other cases, about two-thirds were Protestant or Catholic, and about 30% were nonreligious. That means around 7% belonged to another religious tradition like Judaism, Islam, or Buddhism. Guess what? Those percentages are almost exactly like the general population of the United States. So from this perspective, the religious composition of veterans or veteran families looks just like the average household.

But I think I know why that “none of the above” group is such an outlier based on the previous line graph: age is really a confounding factor. The folks who had nothing to do with military service are significantly younger than the other groups. So to control for that, I’m just going to compare 18–45-year-olds in the last set of graphs. That way, we’re comparing apples to apples.

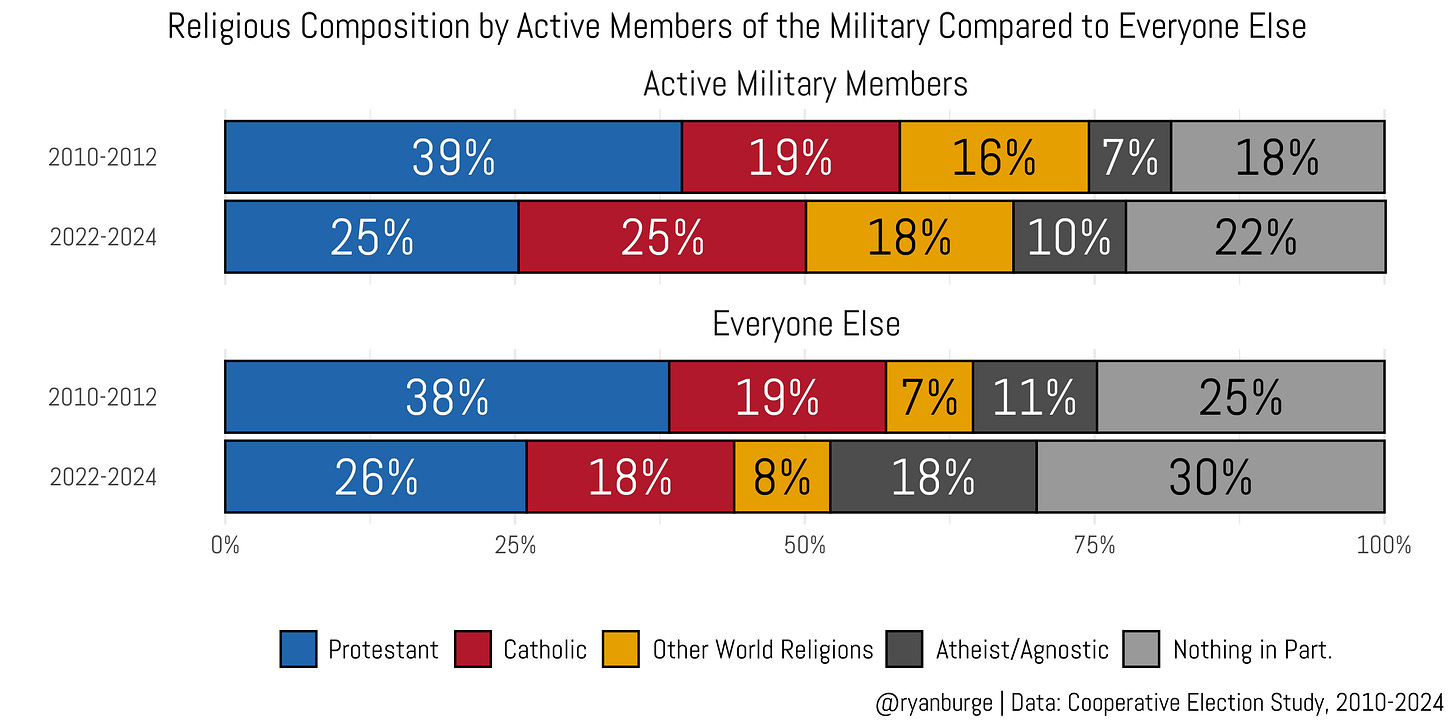

Let’s zero in on active-duty military now. I pulled together samples from the first three years this question was asked (2010–2012) and compared those results to the three most recent surveys (2022–2024).

Yeah, it’s pretty evident to me that the share of active-duty Christians has dropped in a pretty significant way. In the first set of surveys, 58% of members of the military were Christians and 25% were nonreligious. Among military folks in the last couple of years, 50% are Christians and 32% are nonreligious.

But how does that compare with 18–45-year-olds who aren’t actively serving? Well, the Christian share was 57% in 2010–2012 and 44% in 2022–2024. That means members of the military are still more likely to be Christian compared to the rest of the population. Military members are also significantly less likely to be nonreligious: 32% vs. 48% among everyone else. So, yeah, religious affiliation has dropped among both groups, but active-duty respondents are still significantly more likely to be part of a faith group than their counterparts who aren’t currently serving.

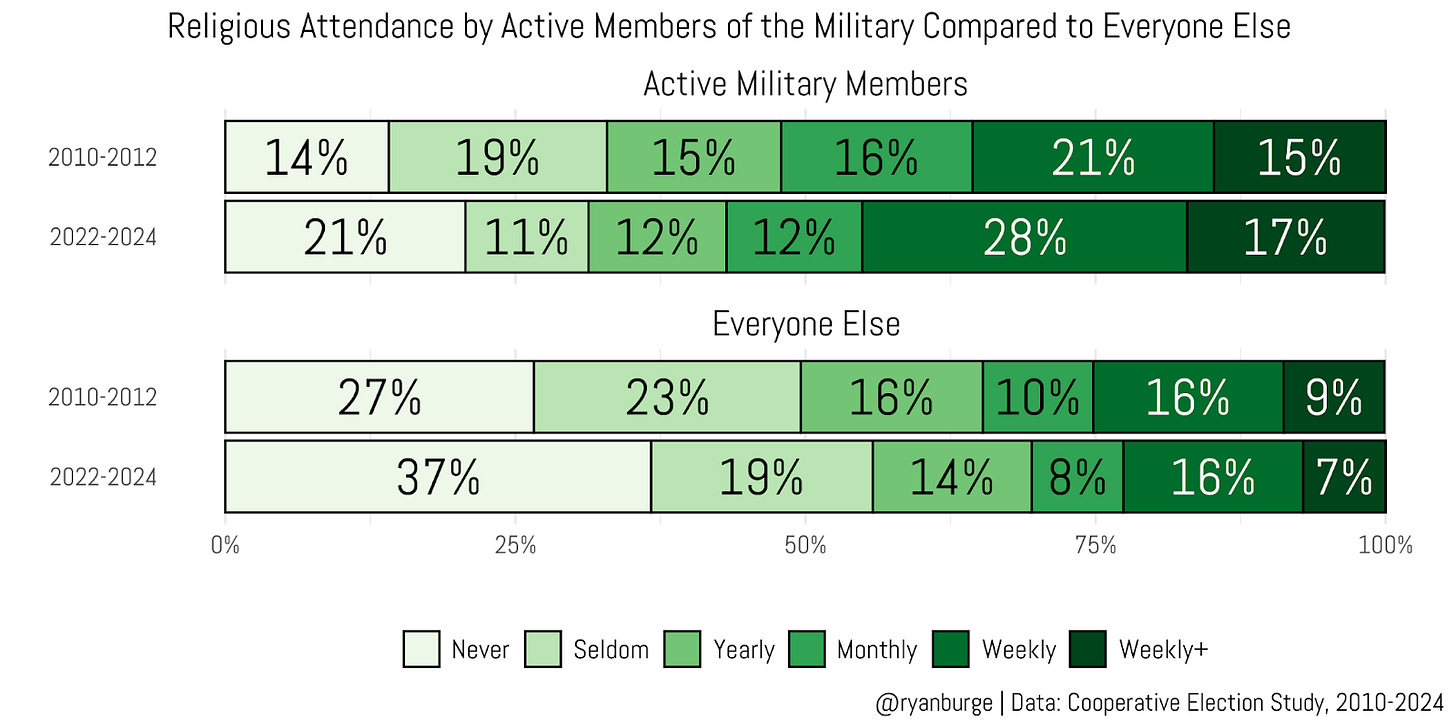

But let’s look at another metric now — religious attendance.

In the entire sample, weekly attendance was about 25% back in the early 2010s. In the last couple of years, that’s slipped a few percentage points and now stands at just 23%. Meanwhile, the share who attend less than once per year went from 50% in 2010–2012 to 56% in the more recent data. So, definitely some secularizing there, too.

But look at the results from active-duty military! This really shocked me. In 2010–2012, the share of military folks who attended a house of worship weekly was 36%. In the most recent data, that number actually rose to 45%. That’s insanely high, honestly. A member of the military is about twice as likely as a civilian to be a weekly church attender. And remember: we’re comparing only 18–45-year-olds in both samples here.

There are two really noteworthy findings here: military folks have always been more religiously active than other Americans, and the devotion of military members has gone up while the rest of the population has secularized.

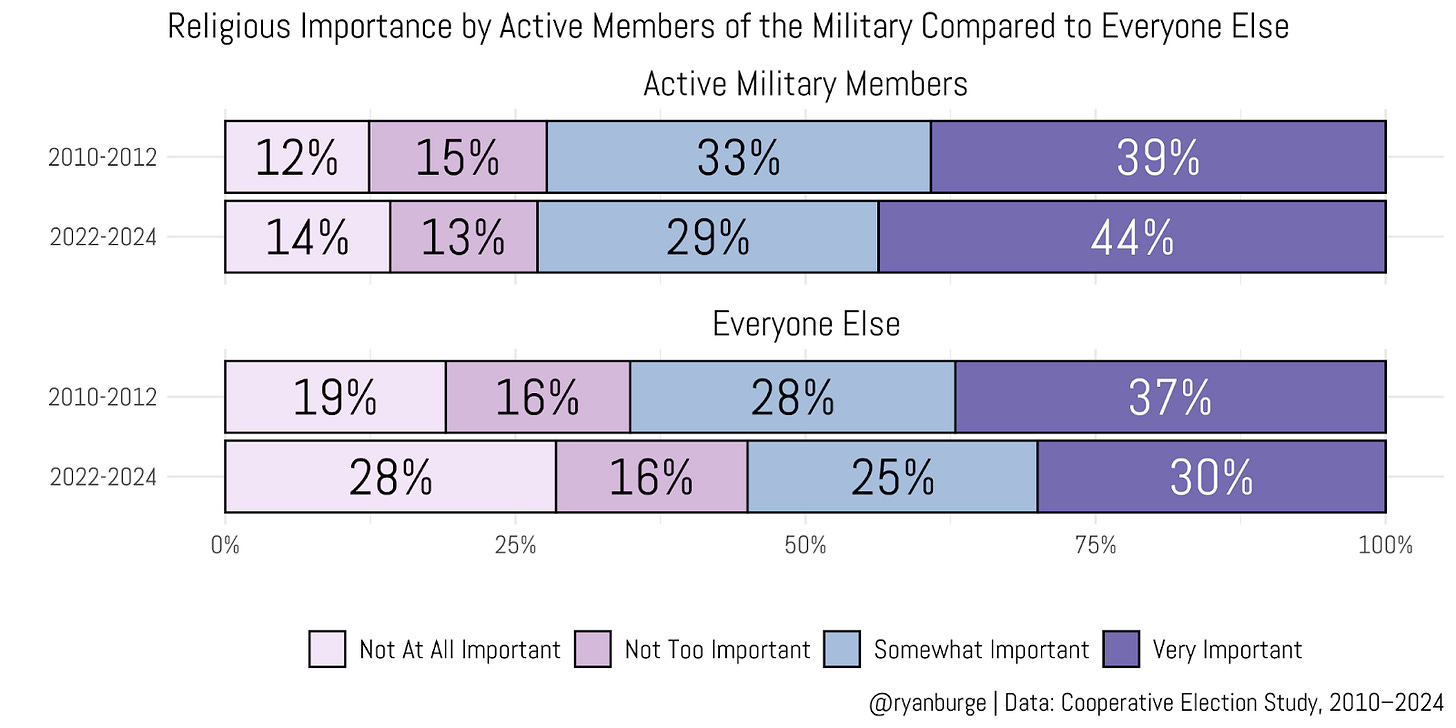

I had to cross-check this with one other metric: religious importance.

And guess what? That finding about religious attendance wasn’t just some aberration in the data — it shows up here, too. In the early collection period, 39% of active-duty members said that religion was very important to them. That was about two percentage points higher than the reference group — just slightly more religious on this measure.

However, in the data collected between 2022 and 2024, 44% of active-duty members said that religion was very important to them. That’s a five-point increase since the first survey collection period. And that shift is even more striking when compared to the rest of the sample: in the general public, religious importance dropped by seven points.

The gap in importance between these two groups was just two points in 2010–2012. Now it’s 14 points. Said as plainly as I can: the American military is actually becoming more religious as the rest of the population moves further away from religion.

Why is this happening? Well, I think there’s a good social science reason: selection effects. We don’t have a draft anymore — the military is all voluntary. People choose to sign up. The reasons for joining are myriad, of course, but the data point to the fact that certain states are overrepresented among recruits. They’re places like South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida.

It doesn’t take a whole lot of guesswork to figure out what’s happening here: the military has an easier time recruiting in areas of the country that tend to lean right on Election Day. Those areas also tend to be more religiously active. It’s not that the military is making its men and women more inclined toward a faith community — they were already that way before they swore the oath.

In other words, this isn’t a random swath of the population. It’s a very specific subset of the United States. Now, I won’t even begin to consider the implications of a military that’s more religious now than it was a decade ago. I’ll let you folks have at it in the comments.

Code for this post can be found here.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

First off, long-time reader, first time commenter since the switch to paid commentariat (indeed, I think I'm the guy

Second, on the small size of respondents who identified as military, I have to note 0.4% is perfectly proportional to the actual size of the AD Military (1.3M counting the Coast Guard in 2023; see the 2023 Force Profile report). So that's really good sampling, actually.

https://demographics.militaryonesource.mil/chapter-2-active-duty-personnel

Although I will note the numbers of some of the respondents in the "Other World Religions" category makes me suspect they oversampled on officers (although that's usually the way it works anyway, so [shrug emoji]).

I'm surprised it hasn't already come up in this discussion or in the comments. I retired from active duty (Army officer) in 2008 after 31 years. There was still a Chaplain Corps, and I believe some were still assigned as staff officers down to the battalion level. In my more junior years, every battalion I was assigned to had a chaplain, usually a Captain. The CONUS hospital where I retired now has a Jewish chaplain, a first in my experience. I'd like to hear Ryan Burge's observations about chaplaincy in the military, and its possible effect on these statistics. Go here for more - https://os56.army.mil/