A Puzzle: Religious Importance, Religious Attendance and Education

Why the highly educated go all-in or all-out on religion

One of my main goals as a professor is to get students excited about the material. In a philosophy of youth ministry class our instructor wrote in big letters on the board, “It’s a sin to bore people with the Gospel.” I’ve taken that to heart and expanded it - it’s a sin to bore people at all.

One way I make data work appealing is by likening it to detective work. We can see a pattern or an odd set of results from a bit of superficial analysis and then we get to poke and prod around to figure out if we can determine the cause of those results. Except we don’t try to pull prints off of doors or windows or extract DNA from dried blood on the floor. We just make graphs.

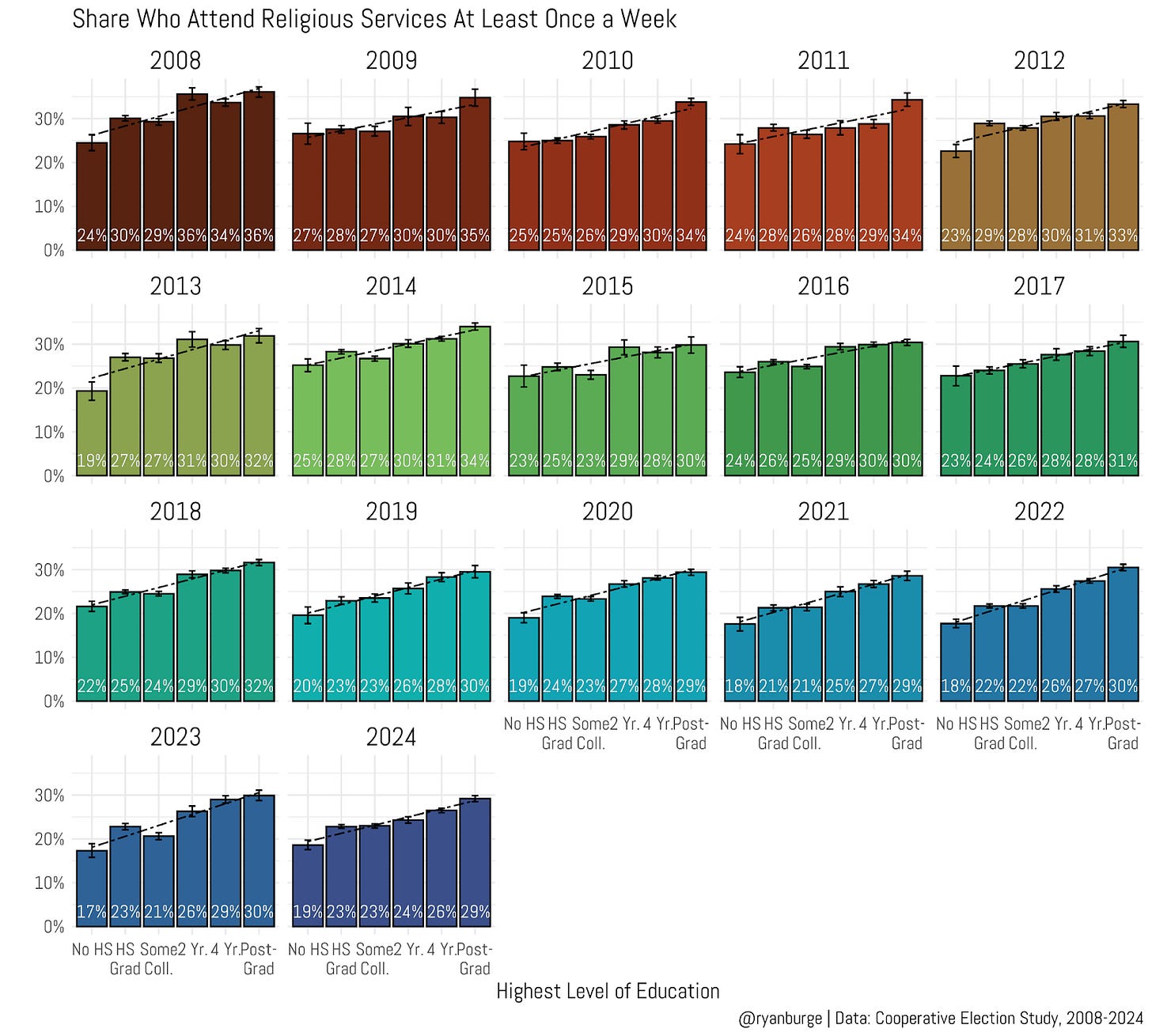

So, let me introduce you to the puzzle for today’s post. This is a graph that I think may be the one that gets the most traction on social media. It’s an incredibly simple one - it’s the share of respondents who report attending a house of worship on a weekly basis. I break it down by educational attainment and survey year.

Long story short, the type of folks who are the most likely to attend a church, synagogue or mosque this weekend are folks who have earned graduate degrees. The ones who are the least likely to be regular attenders are individuals who stopped at the 12th grade. Yes, dear readers, education and religious activity are positively related.

And, I don’t want to repeat myself too much on this, but the highly educated are less likely to identify as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular. Instead, they’re more apt to report belonging to a recognized faith tradition — Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Hindu, and so on than those who stopped their education when they were still teenagers.

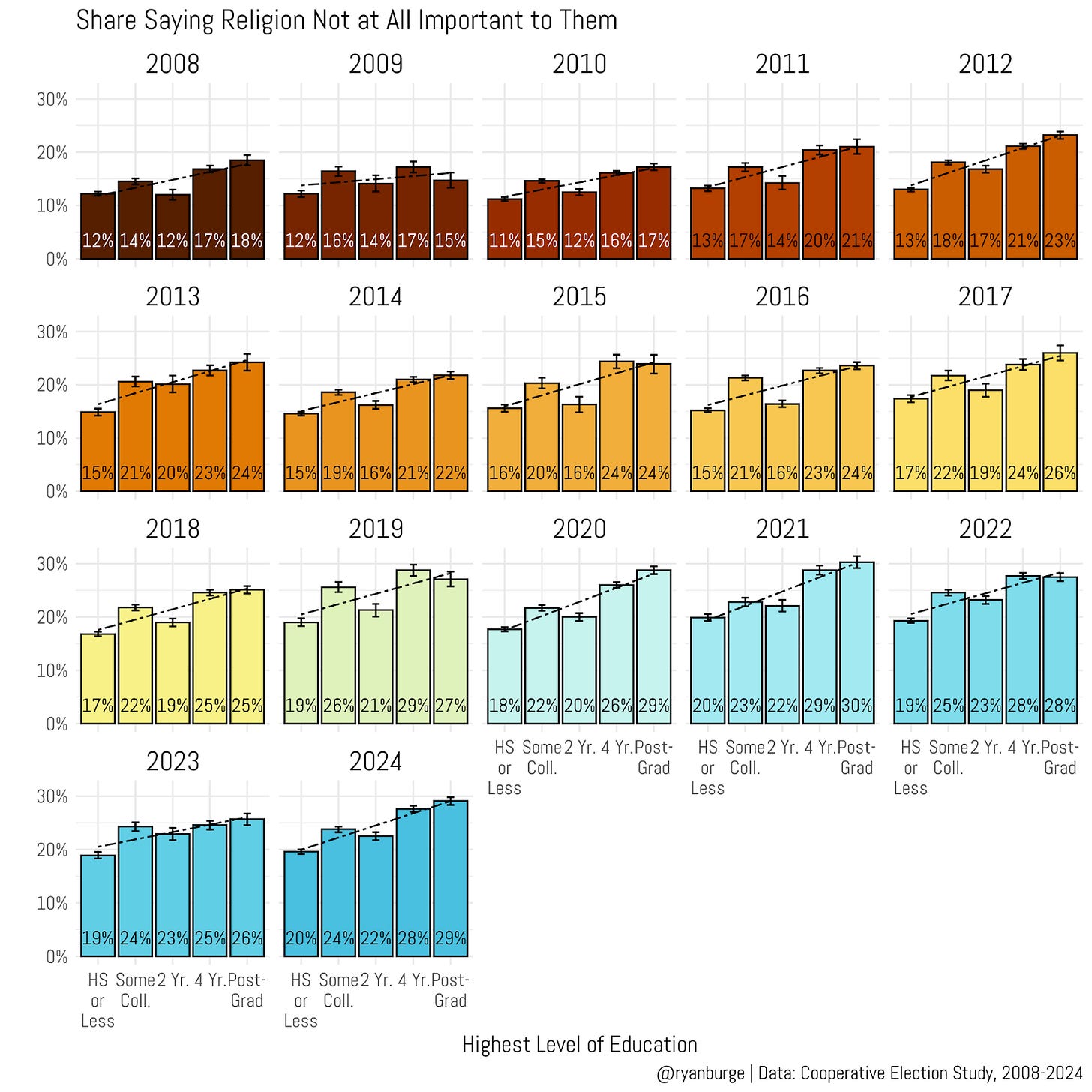

So that’s the backdrop of this. On most metrics, educated folks tend to be more religious. Now, let me show you another metric in this same neighborhood - religious importance. Same basic setup as before, I calculated the share who said that religion was ‘not at all important’ by level of education and I did it for the last 17 years of data in the Cooperative Election Study.

Given what I’ve just told you, this graph should come as a pretty big surprise. In every single year of the survey, the line points upwards. That means that the folks with graduate degrees are more inclined to say that religion has no importance to them than individuals who have a lot less education. These gaps are not small, either. In the most recent samples, about 20% of folks at the bottom end of the educational spectrum said religion is not important to them. It was 30% of the respondents at the top end of the educational ladder.

We’ve got a pretty big contradiction on our hands here, right? On both religious behavior and religious belonging, it’s the educated who score the highest. But when it comes to religious importance, the whole thing flips upside down. That’s an empirical puzzle that’s just dying to be untangled. Let’s try to make sense of these seemingly contradictory findings.

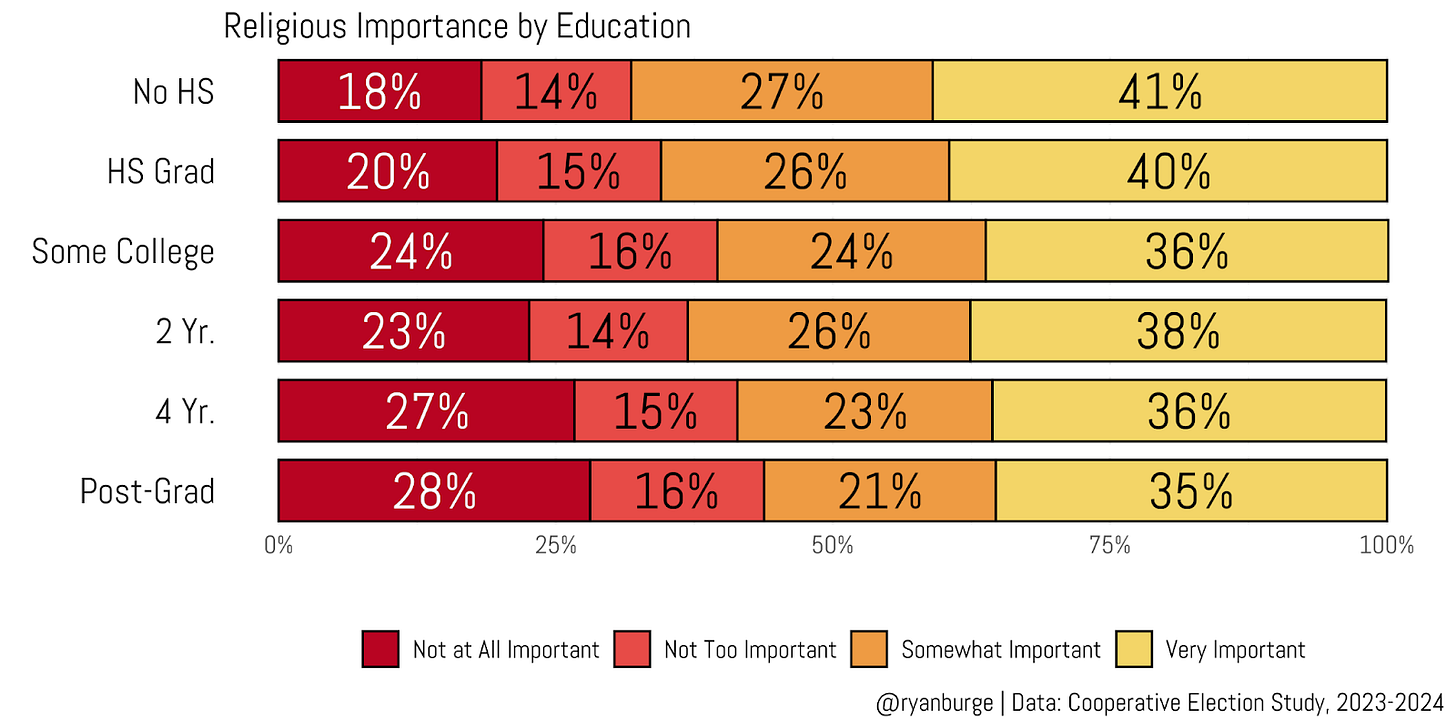

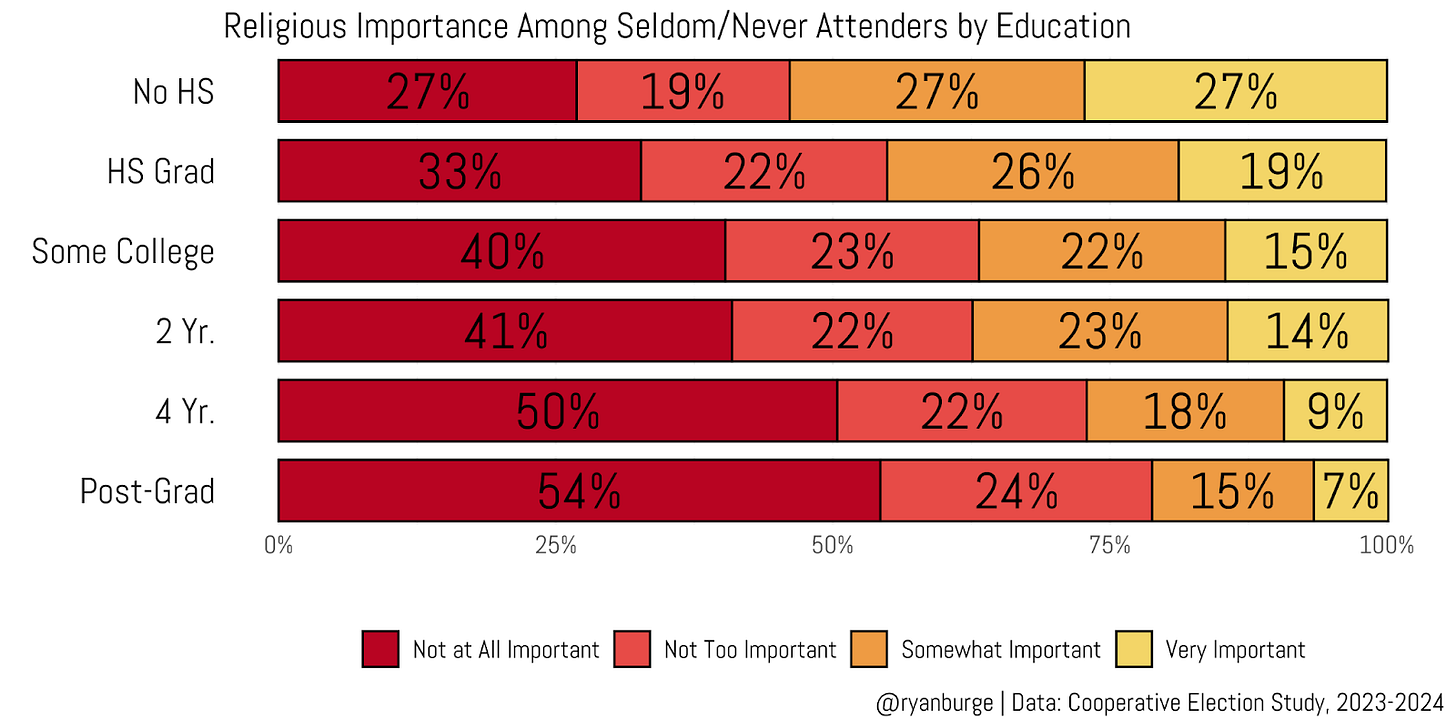

To start with, I just wanted to see the full range of values for religious importance by level of education. I pulled into the last two years of data to make this graph.

Okay, now I am starting to shed a bit more light on what’s actually happening in this situation. Look at the right side of the graph - that’s the share of each level of education that said that religion was very important to them. Notice how small the changes are between education levels? Yeah, it’s very subtle. For someone with a high school diploma, 40% said religion was very important to them. Among respondents with a masters degree it was just five points lower at 35%.

Really the biggest movement is on the left hand side of the graph. That’s folks who said religion is not important at all (which is the metric that we used for the prior bit of analysis). There’s basically a ten point increase in this response option when comparing those with the highest and lowest level of educational attainment. That’s twice as much as the shift in the “very important” metric. If I had used “very important” as my dependent variable in the prior graph, the findings would have been a lot more subtle.

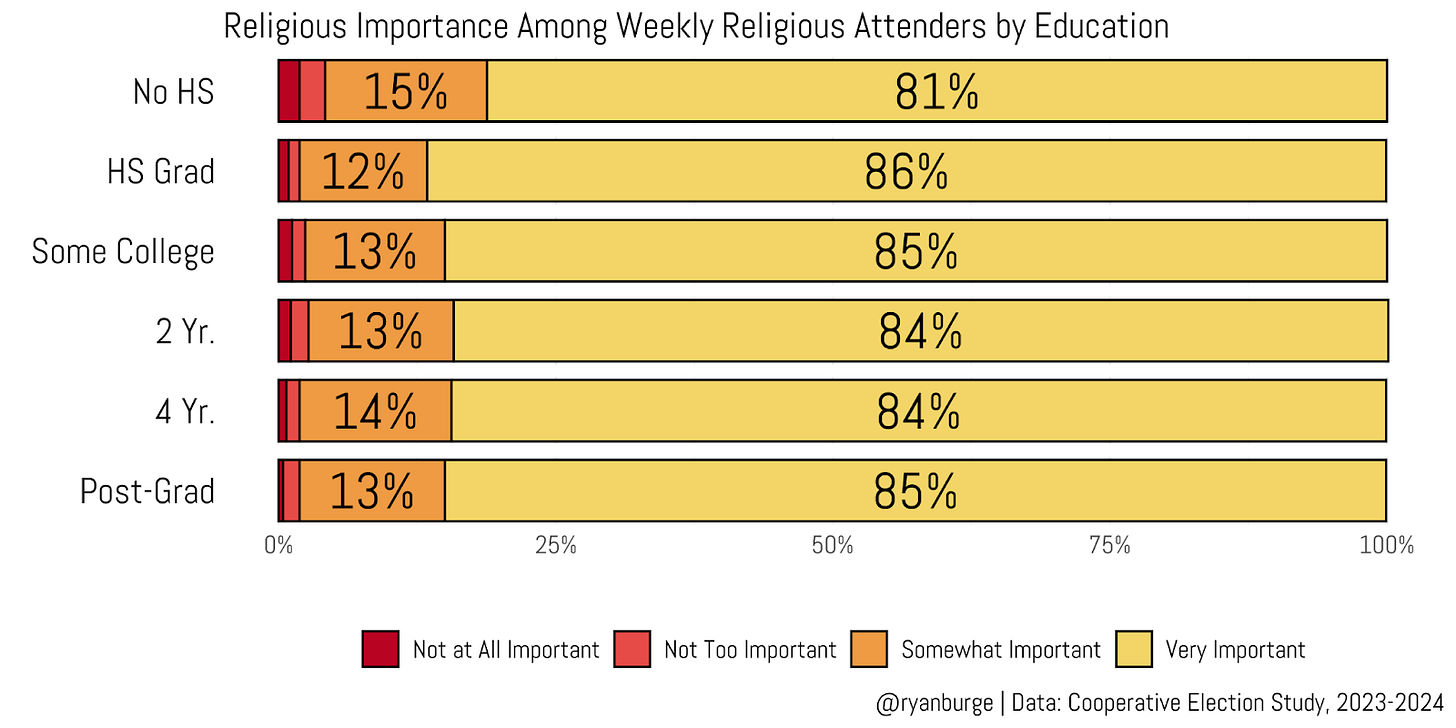

Okay, so that helps us understand one component of this, but I had another theory that I wanted to test out: a lot of highly educated church going folks actually don’t go because they like religion. They go because they like to make social connections and be part of a social group. This matches how the eminent historian Gordon Wood described a lot of the Framers - fairly faithful attenders, but not particularly emotionally religious.

Well, that theory doesn’t hold up on today’s data. For weekly attending folks with a high school diploma, 86% of them said that religion was very important to them. And that’s basically the same number when looking at any level of education. You just don’t see a whole lot of people who are willing to head to a local house of worship on a regular basis purely for sociological reasons. If they are going, it’s because they have internalized the value of faith.

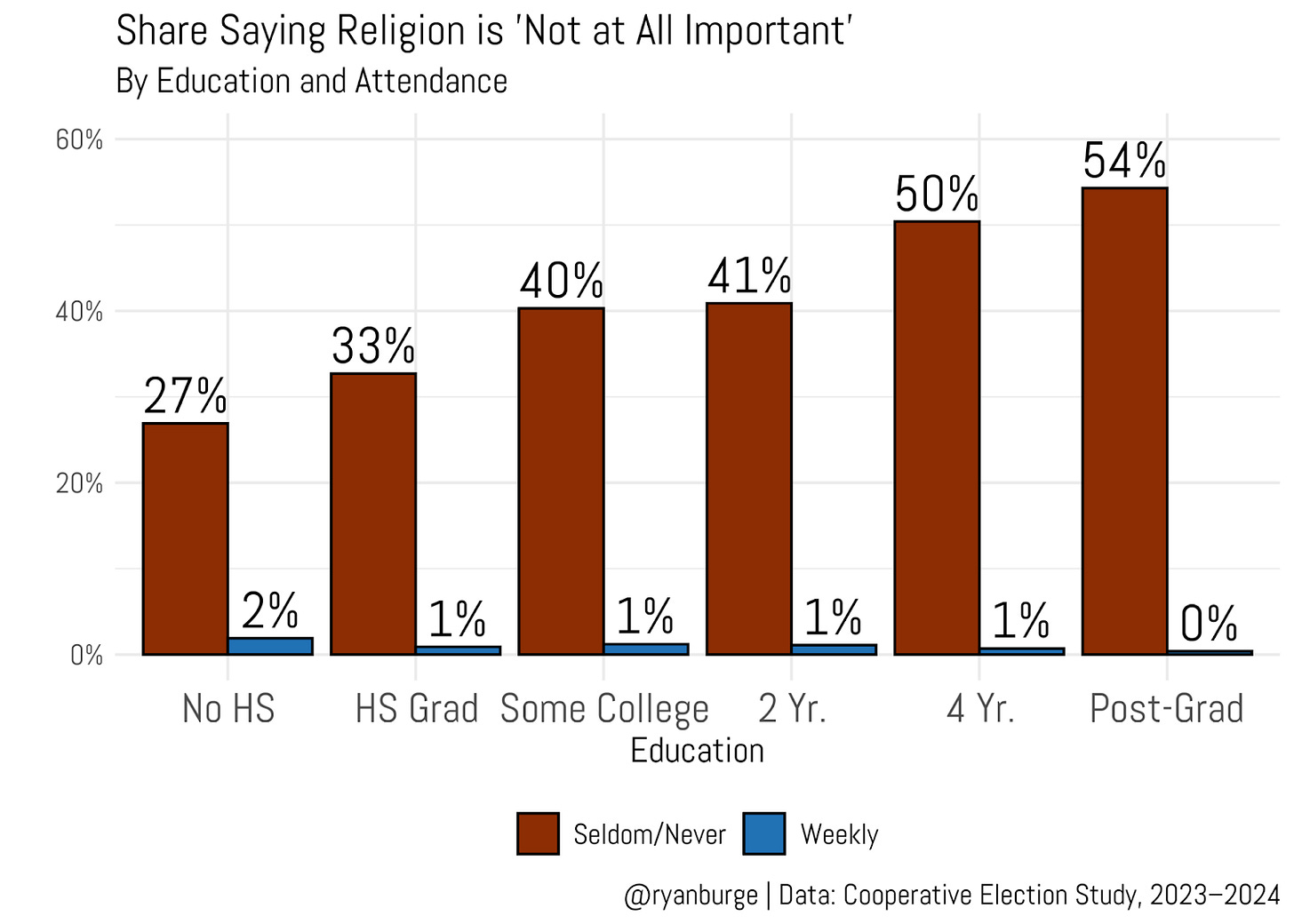

To this point, we really haven’t fully solved the puzzle of why educated folks are more likely to be weekly church attenders but also more likely to say that religion is not at all important to them. So, I had another thread I wanted to pull on - maybe the story is not among weekly attenders but among those who go to church very rarely. So, I created two attendance buckets: those who are seldom/never attenders and those who attend at least once a week. Then I just calculated the share who said that religion was not at all important.

And this is the Scooby Doo reveal moment for me. Now I know why religious importance and religious attendance don’t work the same when looking through the prism of education. Among those folks who didn’t finish high school and also attend religious services less than once a year, only 27% of them said that religion was not at all important to them. Just think about that for a second. These are folks who haven’t gone to church in the last 12 months, and only a quarter of them say that religion is not at all important.

But as education goes up, so does the share of infrequent attenders who say religion is not important at all. For instance, among college educated people who seldom or never attend a house of worship about half of them say that religion is not at all important. That’s a doubling in share from the left side of the graph to the right hand side.

In other words, educated people closely align their religious behavior and their religious importance. If they aren’t going it’s because they are far away from religion. For folks at the bottom end of the education spectrum, they may give up on religious behavior, but many are still hesitant to walk away from religion entirely. That really comes into focus when looking at religious importance among those who attend a house of worship seldom or never.

Look at high school graduates with low religious attendance. About one third of them say that religion is not at all important, while 19% say it’s very important to them. That’s a gap of about 14 percentage points.

For people with some college, the gap widens to about 25 points. But then it takes a huge leap when only looking at respondents with a bachelor's degree, at 41 points. And it’s even bigger among those with a graduate degree - 44 points.

So, here’s what we’ve got.

Educated people are more likely to be weekly religious attenders.

Educated people are also more likely to say that religion is not at all important.

It’s not because there’s a bunch of weekly attending folks who say that religion is not at all important. The more people go, the more inclined they are to say religion is very important to them.

The real answer is this: when educated people stop going to church, they also are more likely to score lower on religious importance. For those with less education, even infrequent attendance doesn’t mean abandoning religious importance.

Here’s why I love my job: answering this question only leads me to consider more questions. Like, Why do educated people tend to move away from religion more completely, while those with less education do not? I don’t have an answer. But you better believe I’m going to try and sort one out.

Code for this post can be found here.

A couple housekeeping things.

From now on, all my posts will only allow comments from paid subscribers. Someone commented that my newsletter has the largest divergence in quality of the post to the quality of the comments. So, let’s fix that by locking down the comments to only folks who are really committed to the community here.

I am doing a speaking gig at Bryan College in Dayton, TN on January 5th. Which means I will be driving through the Nashville area on Sunday, January 4th. If anyone would like me to come speak or preach or both, just let me know. I can give you a discounted rate.

Ryan P. Burge is a professor of practice at the Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University.

The most important requirement for getting a graduate degree is turning up. The second-most important is thinking a lot. So, highly educated people who keep their religion (through thinking about it, or by treating it something for which thought is not apporpriate) are going to turn up. Those who reject it won't go for half-baked intellectual compromises like "somewhat important" I suspect the same is true of "spiritual but not religious".

This seems fairly straightforward. It makes intuitive sense that people who are highly educated are more likely to align their beliefs with their behavior. They aligned their value for eucation with their execution of advanced degrees. They are, in other words, successful people who act on their convictions. Therefore they are also the people who, if they believe religion is important, act on it by regularly attending church.

One of the best predictors of long term success is the gap between what you think you should do and what you actually do. This just further proces the point.